One of many reasons why you shouldn’t look down on people who don’t have your same advantages is that sometimes they flame out and get their revenge. Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, and Napoleon were all from communities that were sidelined to varying degrees, but they made the so-called civilized folks pay attention in the end.

But perhaps none were as sidelined as a little boy named Temüjin. From the civilized and sedentary world’s perspective, he was one of those uncouth, unlettered, and unwashed nomads of the steppe. From the perspective of the nomadic tribes, he was one of the despised Mongols, who didn’t keep their own domesticated herds, but hunted wild animals and sometimes the domesticated animals that belonged to other people. From the perspective of the Mongols themselves, he was a member of a subordinate clan and the son of a captured woman and a father who was already dead.

It’s hard to get much lower than that. This is not an episode on him, so I’m not going to go into the details of a difficult childhood followed by a long, slow rise up to ruler of an unbelievably large empire, but his background had a huge impact on his thinking.

Mongol Women

For starters, Genghis didn’t have a male protector that he could count on. It was his mother, Hö’elün, who always had his back.

For another thing, Mongol women in general held more power than their counterparts in more civilized nations. As I related in episode 2.1, this is often the case. When societies adopt agriculture, settle down, and begin stratifying, the position of women suffers.

That doesn’t mean that Mongol society was a woman’s paradise. The life was hard, successful men had many wives, and Hö’elün was not alone in having been stolen from another tribe. But it is also true that all tents (what we would now call yurts) were owned by the head woman of the family and the inside was her domain. She also owned the carts. Her clan and tribe mattered as much or more to her children than the father’s clan, and since the men were often away hunting, fighting, and/or stealing, the woman was independently managing everything else (Weatherford, 33; de Nicola, Economy, 132).

This was the cultural background when in 1206, Genghis united all the tribes of the steppe. He combined all tribal territories, divided them up, and assigned them to… his wives and his mother (Weatherford, 28). There was plenty of booty assigned to the male relatives and supporters as well, don’t get me wrong, but 90% of everyone else we’ve ever talked about would have given them only to male supporters and vassals. But in Genghis’s mind, it was perfectly natural for women to own property and the home territory. The men would be busy making the next conquest anyway.

So each of four wives got their own independent territory to rule as they saw fit. Of course, they were to help supply the army, no question. But day-to-day management was their domain. Genghis Khan had no doubts about their ability, “Whoever can keep a house in order, can keep a territory in order” (Weatherford, 34). Now it is true that when I followed my secondary source on that back to the primary source, what I found was a slightly different quote: “Whoever can keep his house in order, can keep a territory in order” (Rashid, 294). That was recorded for posterity in Persian, and my Persian is nonexistent, so I can’t say how explicit a gendered pronoun like his would have been. It depends on the language. But it is certainly true that Mongolian men were not keeping houses. Mongolian women were (as long as we keep a broad-minded view of what constitutes a house). And subsequent history would prove that Mongol women could keep a territory in order too.

Alliances were made by marriages, but Genghis Khan seems to have tired of getting married himself. (He had done it several times already.) So many further marriage alliances involved his many children, who were just getting to the age where they could be of use to him. We don’t know their birth order or even exactly how many children Genghis Khan had, but we know far more than I would have expected from a culture whose written language was not even as old as Genghis himself.

The Daughters

We know his oldest daughter was named Khojin, and she married a safe choice, Botu of the Ikires, a tribal ally. The wedding, assuming it followed the traditional pattern, involved Khojin standing in front of the new tent that was to be hers. She put on a very large headdress that signified a queen and walked between two fires. That was the marriage. People brought gifts for eight days and then there was a feast (Weatherford, 30-31).

Khojn’s marriage would be the least impressive of Genghis Khan’s daughters because Genghis Khan was only just getting started. The steppe provided meat and milk and animal hides, but it was short on the luxury goods available in the civilized south. Having come so far in the world, he saw no reason to stop.

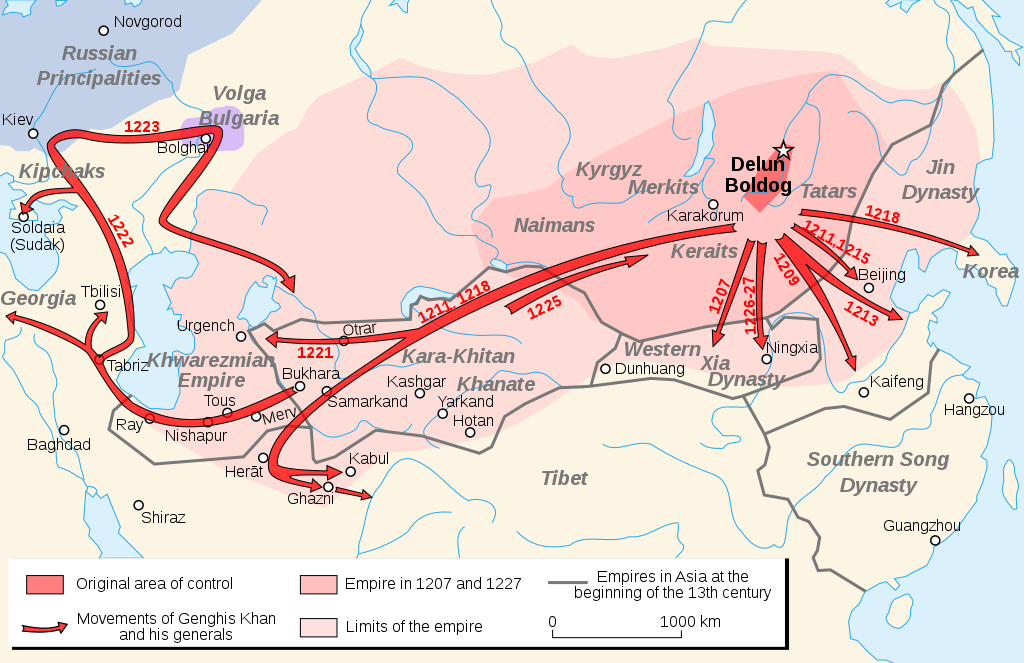

In 1207, Genghis Khan took Siberia. His daughter Checheyigen married the Oirat chief’s son to seal the deal. At her wedding, Genghis Khan made a speech, and his intent is perfectly clear. “Because you are the daughter of your Khan father, you are sent to govern [these] people… You should organize… and control them” (Weatherford, 47; Zhou, 70). This speech is recorded by Chinese sources, and while I have no data on what the Oirat people thought of this.

As early as 1205, even before he unified the steppe, Genghis Khan had tested his men against fortified cities, but he found that city-dwellers could not be trusted. They always promised to send regular tribute, but as soon as his army moved on, they stopped sending the tribute. (Imagine that!) Clearly, he needed someone to stick around and manage things. In 1211, his daughter Alaqai married a prince of the Onggud, a settled people who lived south of the Gobi Desert, nowadays part of China.

The Onggud were Turkic-speaking, and they embraced many religions, including Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, for sure, and almost certainly Confucianism and Taoism too (Weatherford, 70). Alaqai, who was in her late teens, was the first Mongol princess to come down off the steppe and rule over millions of people who had a long history of despising everything she represented. It can’t have been easy.

According to Chinese sources, Genghis Khan gave a speech at Alaqai’s wedding too. He said, many expeditions were coming, and her goal would be to support that. Self-reliance was vital. “Although there are many things you can rely on, no one is more reliable than yourself!” and “Although there are many things you should cherish, no one is more valuable than your own life” (Weatherford, 52; Zhao, 67). One just has to wonder what the poor groom was feeling. This doesn’t sound like your ordinary best man speech.

But… moving on.

There was a reason that Genghis valued Alaqai’s marriage and life so highly. Strategically, her domain was particularly important. In good weather, it took six weeks to cross the Gobi and both men and horses were weak at the end of it. In bad weather, you just didn’t make it at all. With Alaqai holding the land just to the south of the desert, Genghis Khan’s army could rest, and resupply before launching into China proper.

Unfortunately, the Onggud were just as aware of this importance as Genghis and Alaqai. In 1211, just as Genghis had fully committed himself in an assault on northern China, the Onggud revolted. They killed Alaqai’s husband, and she barely escaped with her life.

Genghis was livid. He sent her back with an army and orders to kill every rebel, and every male taller than the wheel of a Mongol cart. This massacre was averted by Alaqai herself. When her army was fully in control again, she ordered that those who had killed her husband be executed, plus their families. But others she spared. She then married her stepson and carried on as if nothing had happened. The Onggud never revolted again and when Genghis Khan took northern China, he gave Alaqai control of that too (Weatherford, 68-71; Zhao, 200). She stayed in her position until her own death, many years later.

Meanwhile, another daughter, another country. The Uighurs were a tribe that controlled a sizeable chunk of the Silk Road. In 1209, they revolted against their Buddhist overlords and being in need of support. They asked the Great Khan for help. He was only too happy to oblige. His daughter Al-Altun married the Uighur leader. Genghis Khan gave a speech at her wedding. Al-Altun had three husbands, he said: first, her nation; second, her reputation; and third, the actual man she was marrying (Weatherford, 60; Zhao, 69). At least he came in third.

In 1211, Genghis Khan married a daughter, whose name is disputed, to the leader of the Karluk Turks. The man’s title was Khan, which Genghis Khan removed from him. It was confusing to have two Khans and anyway people might think the man outranked his wife. Which he didn’t. Like all of Genghis Khan’s daughters, this girl had the title of beki—an ungendered word for prince. His sons-in-law did not get this title. They were just prince consorts. And anyway Genghis Khan usually pulled sons-in-law away from their homes into his personal army, where they tended to have a short life span (Weatherford, 65).

The importance of this Turkish land, though, was that it was the gateway to the Persian lands further south. By 1219, Genghis Khan was ready for that. In 1220, he sent a son-in-law to take the Persian city of Nishapur and they killed him. In 1221, the Mongols were back with Genghis Khan’s daughter in charge. She ordered the city to evacuate. Those who didn’t leave she sorted into two groups: if you had a valuable skill, you could live and serve the Mongols. If you did not, you were dead. The city, she burned to the ground. This story comes to us from the Persian/Muslim record, and they didn’t think it worth mentioning this Mongolian princess’s name. Probably it was Tumelun, but we aren’t positive (Weatherford, 74-76).

It is also possible that they exaggerated the brutality. But true or not, the propaganda suited Genghis Khan’s purposes. It was much better to accede to his demands from the get-go. Things just went easier for everyone that way.

What Else We Know and Why It Isn’t a Lot

By this point, you may be wondering whether Genghis had any sons. Why yes, he did. He had four that we know of. And here is where I do think that my major source for today overstated the case. I definitely got the impression that Genghis ignored his sons in favor of his daughters, so it was quite a shock when I went to the primary source material and found a great deal more about honors for the sons than about honors for the daughters.

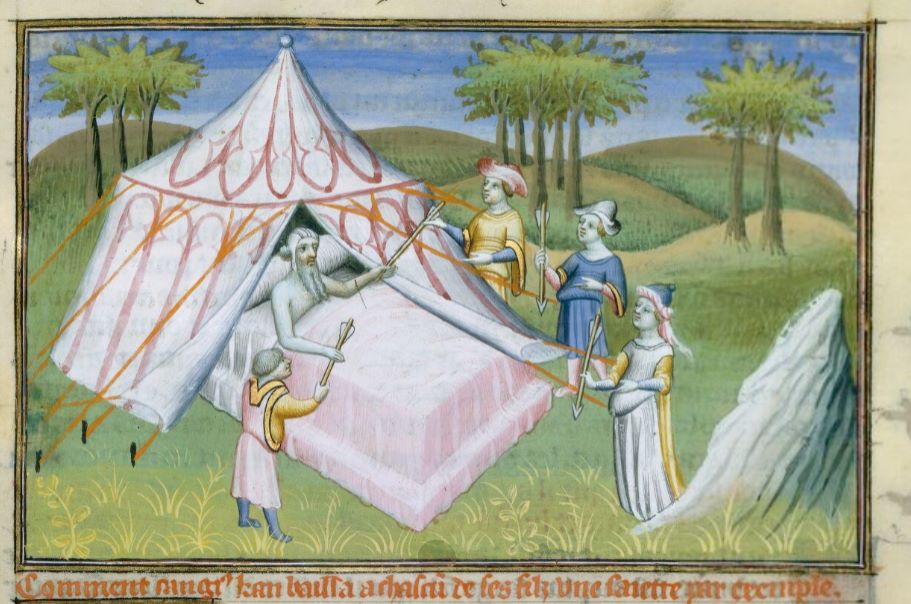

Here’s the thing: Genghis rewarded his sons. Even though they were—and I’m quoting—”good at drinking, mediocre in fighting, and poor at everything else” (Weatherford, xiii). These sons got plenty of booty, captured people and territory, and titles. The primary sources are clear on that. The rewards for the girls takes far more digging to find and I am sorry to say that this is on purpose. The oldest source for anything on Genghis is called the Secret History of the Mongols, written by an anonymous scribe shortly after his death. It includes a great deal about his mother, a bit about his wives, a lot about the position of Mongol women in general, but just after Genghis declares “Let us reward our female offspring” the following section is cut out of the narrative (Secret History §215). Literally, the pages are cut out. So yes, Genghis made a speech about rewarding daughters, a scribe deemed it worth recording, but someone else didn’t want us to know. Probably it was some descendant of the sons who grabbed everything later in Mongol history.

That is why we were forced into Persian and Chinese sources for the rest of the story, and neither of those cultures had any great interest in celebrating great female leaders. Far from it. It is nonetheless a Persian chronicler who recorded these words of Genghis, who said: “My wives, daughters-in-law, and daughters are as colorful and radiant as red fire. It is my sole purpose to make their mouths as sweet as sugar by favor, to bedeck them in garments spun with gold, to mount them upon fleet-footed steeds, to have them drink sweet, clear water, to provide their animals with grassy meadows, and to have all harmful brambles and thorns cleared from the roads and paths upon which they travel, and not to allow weeds and thorns to grow in their pastures” (Weatherford, 39; Thackston, 298-299).

The Mongol empire as a whole conquered more territory and people than the Greeks, Romans, Persians, or Chinese ever managed to do (Weatherford, 63).

In that time, they established the Mongol script which was in official use until 1911 (Weatherford, 80). They also held the Silk Road and kept it open and the trade flowing to the advantage of a great many people, and not just themselves. The held it long enough for a certain Marco Polo to travel along it and meet Kubilai Khan, grandson of Genghis. Marco Polo returned to Europe and publishing a book, which some of his contemporaries thought he made up. However, the book was popular enough that when a certain Christopher Columbus sailed West in order to get East, he took along a letter addressed to the Great Khan of the Mongols. Since no one in Europe knew the name of the current Khan, that part of the address was left blank.

As I’m sure you know, Columbus never made it to any Mongol ruler. But just as a thought experiment, it’s interesting to know how surprised he would have been if had made it. Because the Mongols weren’t done with powerful women. The leader he was looking for? Her name was Mandukhai Khatun.

Then again, maybe Columbus wouldn’t have been surprised to find a woman leading the Mongol empire. Because he had a woman behind him too. You would never have heard of Columbus, if not for Isabella, Queen of Castile, and the subject of my next episode.

My major source today was Jack Weatherford’s The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. You can also see there multiple ways to support the show. I am hoping to grow in 2025, so please take a look and see if there’s a way you can help out, whether it’s signing up as a supporter on Patreon, or on Into History, making a one-time donation, buying from the store, or leaving me a review, a rating, or a recommendation. Finally, I have one further announcement. In this series, I’m going to experiment with a little change in schedule. I am moving to a 3-weeks on, 1-week off schedule, in the hopes that spacing out the main series will allow me to cut down the break time between each series. That means that as this was episode 14.3, there will be no new episode next week, but in 2 weeks’ time, you’ll get that episode on Isabella. The new schedule is just an experiment. It may get tinkered with again. If you have feedback on it or anything else, please send me an email at herhalfofhistory@gmail.com. Thanks!

Selected Sources

De Nicola, Bruno. “Women and Politics from the Steppes to World Empire.” In Women in Mongol Iran: The Khatuns, 1206-1335, 34–64. Edinburgh University Press, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09twn.8.

De Nicola, Bruno. “Women and the Economy of the Mongol Empire.” In Women in Mongol Iran: The Khatuns, 1206-1335, 130–81. Edinburgh University Press, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09twn.11.

Rachewiltz, Igor de, “The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century” (2015). Shorter version edited by John C. Street, University of Wisconsin―Madison. Books and Monographs. Book 4. http://cedar.wwu.edu/ cedarbooks/4

Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb. Compendium of Chronicles. Translated by W.M. Thackston, Harvard University Press, 1998, archive.org/details/rashiduddin-thackston/page/71/mode/2up. Accessed 10 Dec. 2024.

Weatherford, Jack. The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire. New York, Broadway Paperbacks, 2015.

Zhao, George Qingzhi. Marriage as Political Strategy and Cultural Expression, Mongolian Royal Marriages from World Empire to Yuan Dynasty. 2001, http://www.collectionscanada.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp04/NQ58604.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.

I love it when you do episodes on non-European/American women. I feel like I’m learning the most. But oooooh, I got full-body chills when you mentioned Isabella– what a great intro into the next episode.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I really enjoyed learning about Isabella, and I’m looking forward to sharing it!

LikeLike