If Henry had stopped at two wives, my guess is that your average person wouldn’t know any more about him than they do about Henrys #1-7. But he did have six wives, and that made him so famous that people write award-winning musicals about him. Or rather about his wives. He is the connecting thread, but they are the story.

Unlike many of my other heroines, these women have so many possible sources that I will not have time to cover even a fraction of what can be said about them. That is why you should check out The Tudor Chest podcast, run by Adam Pennington, who also runs Simply Tudor Tours. Adam has fascinating episodes about Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, but also many of the people and social issues that surrounded them. I highly recommend that you go straight there after you finish this episode. In the meantime, here we go:

Catherine of Aragon, Wife #1

Henry’s first wife did not expect to marry him at all. Catherine of Aragon was the youngest child of Isabella I of Castile. Catherine grew up knowing that a woman could inherit, could hold her own, could outmaneuver and outlast the men in her life, could succeed at what many thought was a man’s job. This background will be important.

Long negotiations between England and Spain had settled that Catherine would marry the Crown Prince of England. His name was Arthur. Henry was the little brother.

In 1501, Catherine, age fifteen, arrived as promised. King Henry VII scoped her out and decided she would do. A certain Thomas More said, “she thrilled the hearts of everyone” (Guy, 8).

The wedding took place, and all seemed well for five months until Arthur died, causes much disputed.

The succession was reasonably straightforward to fix. There was a one-month wait to make sure Catherine wasn’t pregnant, and she wasn’t. So the spare became the heir, which is exactly what a spare is for. The problem was what to do with Catherine.

An Anglo-Spanish alliance was still an attractive prospect, and there was still a princess and a prince, but negotiations had to begin afresh. Catherine hung around helplessly while she was alternately told that she’d marry Henry (six years her junior) and also that she wouldn’t marry him. The idea of marrying the aging Henry VII was also floated, but Isabella said no, that’s disgusting. Then Isabella died and that left Catherine caught between her father and her father-in-law, neither of whom had her best interests at heart.

Besides the political alliance and the age issues, there was the Bible to consider. Leviticus 20:21 says “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.”

But all you really need to get around that is a dispensation from the pope, and then no worries. The dispensation would be easier to get if the marriage was unconsummated, so for the first (but not the last) time, the exact nature of Catherine’s sexual relations became a matter of public debate.

She said there had been no sex, which was not unheard of for a young, inhibited couple in a marriage arranged by their parents (see episode 2.5 on Catherine the Great and 12.9 on Marie Antoinette for other examples). But others swore that Arthur had led them to believe otherwise. And it wasn’t just the pope who needed convincing. Because if the marriage had been consummated, then Spain owed England the rest of Catherine’s dowry. And if it hadn’t, then England owed Spain the return of the first part of her dowry, plus Catherine herself. The bickering went on. For years.

It seems to me that Catherine was the only living person in a position to know whether her marriage had been consummated or not, but we couldn’t possibly just take her word for it, could we?

In the end, the papal dispensation was granted, and it included a clause that would come back to haunt Catherine. It said her marriage with Arthur was “perhaps” consummated. In other words, the pope really didn’t care.

But Catherine would come to care. She would very much care.

There was still the money to consider, and ultimately Catherine was saved by a knight in shining armor. Literally.

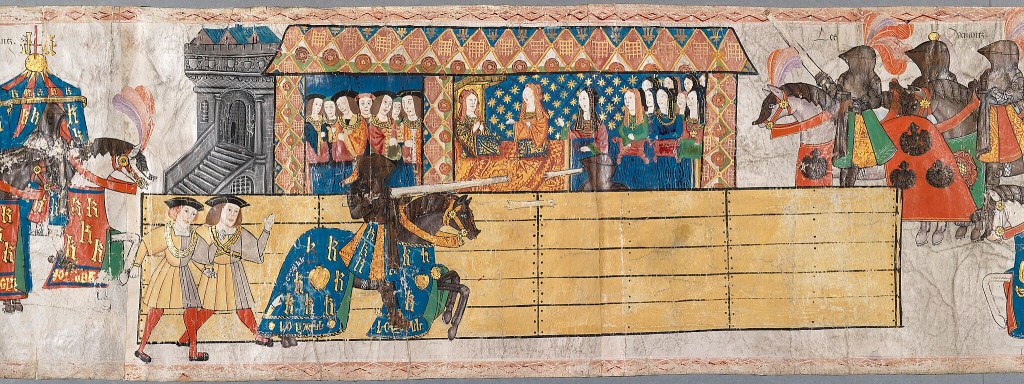

Henry VIII succeeded his father when he was just shy of his 18ᵗʰ birthday. He was young, handsome, charming, musical, good on the jousting field. He was everything a Renaissance prince should be. He had ideas of his own, and he wanted Catherine.

In a world used to cynically organized marriages between royals who had never met each other, Henry chose for himself. He chose a woman he knew, and he gave every appearance of loving her. It was very romantic, and if he had stopped here, the modern world would admire him.

Catherine’s long agony was over. And the next long agony had just begun.

A queen’s most important job is to provide an heir and a spare, and Catherine certainly tried. She became pregnant quickly. She lost that first pregnancy six months after her wedding.

A year later, she delivered a boy. Two months later he was dead.

The dates here become uncertain, but it was miscarriage after miscarriage, maybe seven in total.

On February 18, 1516, Catherine at last gave birth to a healthy baby… girl. In other words, a disappointment. But at least little Mary proved Catherine was capable of carrying a baby to term.

She lost another baby later that same year. She was in her thirties by now, which in their world was old for a healthy pregnancy.

More to the point, Henry, once so patient and loving, had run out of both qualities.

Tudor kingship was not for lightweights. The Renaissance was a new world, and it was no longer enough to be a good war leader. In the words of author Lucy Wooding, Tudor Kings “needed to fight their own wars, dispense their own justice, and at the same time project all the style and charisma of the modern celebrity, as well as balancing their books and overseeing an administration. And for the first twenty years, Henry performed all this with considerable skill” (Wooding, 175). Like I said, there was much to admire about Henry.

The trouble was that success went to his head. He had always possessed an easy self-confidence. It was part of his charm. He would soon demonstrate how uncharming it is when being self-confident spills over into being merely self-centered.

Henry was quite sure that his lack of an heir wasn’t his fault. Nothing was his fault. But in this particular case, he even had proof. He had an illegitimate son because no matter what the marriage vows said, no one really expected him to be faithful to his wife. Expectations were so low, in fact, that even modern writers have congratulated him on having only a few mistresses (Wooding, 176), as if that proves what a good husband he was. If you ask me, that right there encapsulates why feminists are frequently so angry, but I have no doubt that he congratulated himself on exactly the same grounds.

In 1525, Henry had his illegitimate son knighted and titled in a huge public ceremony even though the boy was only six. Catherine spoke out against it because it was clearly a move toward recognizing him as an heir. Henry responded by sacking three of her ladies who had supposedly encouraged her to criticize him. (But he’s a good husband, remember? Because he only betrayed his marriage vows a few times while Catherine was risking her life over and over to give him a son.)

Anyway, moving on.

Catherine considered her daughter Mary as a viable heir. Why wouldn’t she? Not only was she was a woman herself, she was the daughter of Isabella, queen of Castile. Isabella had proved a woman could do this job and do it well.

As far as I can tell, Henry never gave any serious consideration to declaring Mary the heir. Instead, he decided that God was cursing him. Now, suddenly, he was concerned about that verse in Leviticus and being childless. Never mind that he and Catherine were not childless. But in Henry’s mind, child meant male child, so Mary didn’t count.

Having traveled so far in his thoughts, Henry explained the gravity of their spiritual peril to Catherine, supremely confident that she would also see the error of their ways and immediately agree to an annulment.

You can tell just how self-absorbed he was by the way he was genuinely surprised by her tearful reaction.

You may have heard the old rhyme for Henry’s wives: divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived. But actually Henry did not ask Catherine for a divorce. He asked her for an annulment, which was far, far worse.

An annulment meant their marriage had never existed at all. It meant, most likely, that she had lied about her relations with Arthur, that she should never have been queen, that every one of the pregnancies she had lost should never have happened, that she should hand over her title, her jewels, her income, her place at court, her entire identity. And perhaps worst of all, it meant her daughter Mary was an illegitimate bastard who shouldn’t expect to inherit anything.

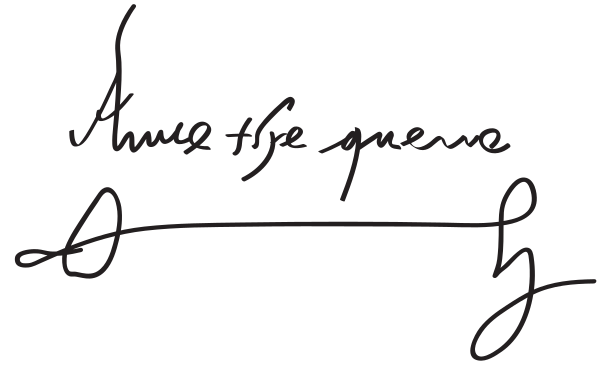

Catherine, Queen of England, looked at her lord and master, and said no.

Henry was stunned.

He was even more stunned to find that a great many people were on Catherine’s side. I won’t speak for God’s opinion of the marriage, but in the eyes of the pope and the English people, the marriage was valid, and Catherine was queen.

What followed was a protracted legal battle, which I think also shows how much the world had changed in the Renaissance. (In an earlier age, a little poison might have solved everything. A couple of armies could have settled it too.) But instead, both sides mustered their religious scholars in a battle of words. Catherine personally appeared before an English tribunal, where she showed herself to be every inch Isabella’s daughter. She was magnificent, and Henry did not win.

The argument was referred to Rome, and it went on for years. The accusations were bitter and wide-ranging on all sides. Catherine was accused of everything from not being a virgin when she married Henry, to smiling too much, to encouraging treason and rebellion (Tremlett, 296).

Once again, the issue was muddier than just interpretation of scripture or even the need for an heir. Because Henry quite clearly had a little lust in the game. His concern for purity before God and a legitimate son was a little too conveniently aligned with his concern for Anne Boleyn to be taken seriously.

Among modern lovers of Tudor history, it is possible to align yourself on Team Catherine or on Team Anne. I have just given you the argument for Team Catherine, so let’s establish the case for Team Anne.

Anne Boleyn, Wife #2

Anne Boleyn was the younger daughter of one of Henry’s diplomats. She had grown up in the French court and only recently returned to England. She was not conventionally beautiful by the standards of the day, but she had wit, charm, musical talent, fashion sense. Basically, she was glamorous, and Henry noticed.

What she was not was meek, submissive, or demure. She could tease. She could challenge. She could make jokes. It only increased her allure. She was not a ditzy blond teenager, the way a certain musical has portrayed her. (In the production I saw, she was blond. I have since been told that she isn’t always blond in the musical Six.)

The real Anne Boleyn was neither ditzy, nor blond, and she wasn’t a teenager. Her exact age is a matter of dispute. Some of my sources said that when this began she was 25, considered mature in Tudor times. Maybe even a little too mature for a first marriage. Adam Pennington of the Tudor Chest favors younger age, for the simple reason that even after years of a legal dispute no one claimed she was too old to bear an heir. But regardless of her age, she was a woman with a head on her shoulders.

Marriage was Anne’s goal. That was what she had come to the English court for. She could not have counted on catching the eye of the king. No one else was going to offer for her once that happened. They wouldn’t dare.

So Anne retreated from court. There are at least two ways to view this, and we just don’t have the historical documents to prove it either way. The view that is most appealing to modern sensibilities is that Anne was a strong woman determined to plot her own future. She knew that to stay at court would leave her as nothing but the king’s mistress, entirely at his mercy, to be tossed aside as soon as he happened to tire of her. This had already happened to her older sister.

Instead, she told the king that he could have her, but only if he made her queen. It was a very clever way of saying no, without actually saying no (Guy, 125). Having set her sights on queenship, she carried it off, which makes her even more appealing to modern ears. This is the woman-ahead-of-her-time interpretation, and there is plenty of evidence to back it up.

But we don’t actually know what was in her mind when she retreated to Kent, and to me it seems a little unlikely that she really imagined becoming queen was possible. To me it also makes Anne a little unappealing. I’m all for a woman dreaming big and plotting her own course in life, but in this particular case, the career plan was to take the job and the husband of another woman, and I’m not a big fan of that.

Another interpretation is that Anne retreated because she was the victim of sexual harassment, and she was trying to get out-of-sight, out-of-mind. It’s less appealing from a feminist perspective, but it is very, very relatable.

If so, her plan didn’t work. Absence made the heart grow fonder. Henry wrote letters to her, some of which have survived, and they are beautiful love letters. The heart would throb, if only he wasn’t already married.

Since the letters are undated, it is very difficult to establish a timeline. We also don’t have Anne’s responses. But whether she started as a victim or a career woman, at some point, Anne realized that for her it was going to be Henry or nothing. And if that was the case, then it was going to be her or Catherine. She didn’t want to be just a mistress, and I don’t blame her. She came back to court, where she was a lady in Catherine’s own household, a situation that must have been miserable for everyone (Tremlett, 258).

There is an argument that Catherine should have accepted reality and stepped aside. Henry was far from the only person who thought a daughter should not inherit. The vast majority of the English agreed. A son would be far more stable. So Henry and Anne could claim the moral high ground here: they were doing what was best for the country. It was selfish of Catherine to insist on remaining queen when it was clear that she could not provide an heir, much less a spare. Isabella’s example was far away. England’s own great success with reigning queens was still in the future.

Meanwhile, from the way Henry wrote to Anne, the modern world would naturally assume there was hanky panky going on in the bedroom, and the modern world would be wrong.

Since Henry obviously had no problem betraying his legal wife, the question is why not. Again, it is quite possible that this was Anne’s choice. She would be a wife or she would be nothing (Guy, 125).

But it is also possible that the decision for abstinence came from Henry. He did not need another illegitimate son. He wanted Anne to provide a legitimate one, and that required at least the appearance of virtue while they appealed to the pope. So it was abstinence. Probably they didn’t realize for how long, but it was nonetheless a decision based on policy, not on passion.

Purity didn’t help them. The pope remained unmoved.

In February 1531, Henry demanded to be recognized as the supreme head of the English church (Gristwood, 164). Not because he was a Protestant. Neither he nor Anne approved of Martin Luther. But he was sick and tired of being told he couldn’t have an annulment. So he approved the annulment himself.

In May 1533, Catherine was informed that her marriage was null and void. She had already been told that she was no longer queen. Jewels, servants, and income were stripped from her. She was not allowed to live with her daughter Mary, though they did write to each other (Gristwood, 166; Tremlett, 330).

A month later, Anne was crowned queen, and three hundred boats sailed the Thames in a grand procession.

Henry and Anne had clearly dropped their abstinence-only policy a little early because Anne was visibly pregnant—after years of no pregnancy even though everyone knew the king’s desires. A celebration was planned for the birth of the prince in September. Only it wasn’t a prince. Princess Elizabeth was born September 7, 1533. The celebrations were cancelled.

And so Anne’s agony began.

In 1534, she had a miscarriage, and another in 1535. The tension was palpable.

Anne also found, like women before and after her, that a man who can humiliate his first wife with a very public affair, can humiliate his second wife with a very public affair. The time-honored way to handle it was to pretend not to notice. But Anne wasn’t much for doing things the time-honored way. She complained.

Henry told her to “shut her eyes and endure … as more worthy persons had done.” In other words, as Catherine had done (Gristwood, 172). This was a low blow.

In 1536, Catherine died of natural causes. She sent Henry a final letter, in which she very sweetly forgave him for everything. But she also signed it “The Queen” (Gristwood, 177).

On the very day of Catherine’s funeral, Anne had another miscarriage. She was far enough along that they knew the baby had been a boy (Gristwood, 178). It must have felt like the judgment of God.

Henry was also suffering. He had taken a hard fall in a joust. His leg would never fully recover, and some historians believe he suffered a brain injury as well. At any rate, his personality, which had once possessed many good qualities mixed in with the arrogance, took a strong dip into negative territory.

Anne’s fall was swift and hard. On April 30, 1536, a court musician named Mark Smeaton swore he had had sex with the queen multiple times. Possibly his confession was made under duress, but also possibly not (Guy, 357-358; Gristwood, 183). Anne and Henry are also known to have had an argument, presumably over these accusations of adultery (Guy, 359).

On May 1ˢᵗ, Anne presided over the joust and tossed her handkerchief to a contestant named Henry Norris (Gristwood, 183). Henry the king was angry. He packed up and left in the middle of the tournament. Anne had no idea why he was upset (Guy, 360).

On May 2ⁿᵈ, Anne was summoned to Privy Council and formally accused of adultery with three men, including Mark Smeaton and Henry Norris. She wasn’t told the name of the third man. It later turned out to be her own brother George Boleyn. She was taken to the Tower and over the next ten days more men were added to the charge (Guy, 361).

On May 12ᵗʰ, four men were found guilty, though Mark Smeaton remained the only one who admitted guilt (Guy 381-383).

On May 15th, Anne was brought to trial and charged with twenty acts of adultery, three of them incestuous. Two thousand spectators watched this trial, in which Anne admitted that she had been jealous and overly proud but declared absolutely that she had not been adulterous. Twenty-six of her so-called peers declared her guilty (Gristwood, 187-188; Guy, 388-392).

Modern historians are sure Anne was innocent, at least of these specific crimes. She could not be guilty because she and the accused men were simply not in the right places at the right times to be guilty (Gristwood, 185; Guy, 380).

But innocence meant nothing. The trial was a foregone conclusion in a way that Catherine’s battle never had been. The hired executioner was already on his way to London before the trial was even over (Gristwood, 188).

On May 17, the men were executed, and Anne’s marriage was annulled, just like Catherine’s had been. Now she had never been queen at all. She was also told she would die the next day at 8 a.m., but the time pressed on and no one came for her. It was not a reprieve but a continuation of her own personal hell. So much so that she said to the constable, “Master Kingston, I hear say I shall not die afore noon, and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought then to be dead and past my pain” (Guy, xxvi).

In fact, she did not die until the next day entirely. On May 19, Anne was taken from the Tower and led to where the crowd awaited. As was customary, she was given a chance to speak and by custom she should have admitted her guilt and praised the king. She did praise the king. She did not admit guilt (Guy, xxix).

One of the unknowable mysteries is what Henry himself believed. Did he coldly calculate Anne’s death? Or did he genuinely believe the accusations against her? It is possible that the coldly calculating mind was Thomas Cromwell’s, the chief minister. He certainly presided over the trials, and he had no love for Anne. The two of them had clashed over what to do with the money confiscated from the formerly Catholic monasteries. Anne favored using it for education and social welfare. Cromwell favored keeping it all for the monarchy. So maybe Cromwell drummed up the charges and truly convinced Henry.

My own view is it doesn’t matter. Henry was always too eager to believe whatever righteous rationale justified the action he had already chosen. And that’s not a lot better than being coldly calculating. A certain Jane Seymour was as unlike Anne as it was possible to be, and Henry had plans. I’ll be talking about that next week.

In the meantime, are you on Team Catherine? Or on Team Anne? Or are both of them just absolutely heartbreaking?

Selected Sources

Fraser, Antonia. The Wives of Henry VIII. Vintage, 30 Apr. 2014.

Gristwood, Sarah. The Tudors in Love. St. Martin’s Press, 13 Dec. 2022.

Guy, John, and Julia Fox. Hunting the Falcon. HarperCollins, 24 Oct. 2023.

Tremlett, Giles. Catherine of Aragon: Henry’s Spanish Queen : A Biography. London, Faber And Faber, 2011.

Weir, Alison. The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, 1 Dec. 2007.

Wooding, Lucy. Tudor England. Yale University Press, 11 Oct. 2022.

[…] you haven’t read last week’s episode, I recommend doing that to get up to speed because today I’m just jumping in. We left Henry, […]

LikeLike

[…] itself. It was semi-traitorous to suggest otherwise. (In some ways, he’d have gotten on well with Henry VIII, who was certainly no […]

LikeLike