Ben Franklin was born in 1706, and he would grow up to be the most famous American of his generation. (The other super famous founding fathers were significantly younger.) Ben had a glittering career as a printer, a writer, a statesman, a diplomat, an inventor, a scientist, and more. But he didn’t do all of this without help, and he admitted as much himself.

The Courtship

The Read family came from Birmingham, England. Somewhere in the first decade of the 1700s, they emigrated to the America colonies and settled in Philadelphia. Somewhere in that same decade, they had a daughter named Deborah. We’re actually not sure whether she was born in England or in America.

We have zero information on her childhood. She bursts into the record in a charming scene written by the master of charm himself. As a middle-aged man, Ben wrote an autobiography, in which he recalled that in 1723 at the age of 17, he ran away from his apprenticeship in Boston. He went to Philadelphia, and on his first day he bought three pennies’ worth of bread because he didn’t know that a penny was worth more in Philly than it was in Boston. He ended up with so much bread that had to stuff one great puffy roll in his mouth and tuck another under each arm as he walked away, feeling ridiculous.

He wasn’t the only one to think he was ridiculous either, for the teenage Deborah Read was standing in her doorway watching him, and she giggled (Franklin, chapter 3).

Months later, he rented lodgings from her parents. By then he had cleaned himself up, learned the value of a penny, and gotten a job at a print shop. She no longer thought him ridiculous. It’s likely that she found him fascinating because throughout his life, most women did. He was tall, muscular, witty, gregarious, not to mention brilliant (Isaacson, 37).

It’s less obvious what Ben saw in her. For many years, American historians portrayed Deborah as dumpy, shrewish, sadly uneducated, and altogether unworthy of her sparkling husband.

More recent historians have been kinder: Deborah had all the education a woman of her time and social status was expected to have. Of course, it didn’t match his, but Ben would not have seen that as a drawback. As for dumpy and shrewish, support for those accusations is all from comments made much later in life (and some of them are second or third hand at that). They surely don’t reflect how she was as a teenager.

The point is that the young people were showing signs of mutual interest, and Deborah’s mother considered that a problem. Ben was charming, but you can’t eat charm. His job was not the sort that could support a wife (Franklin, chapter 5).

Fortunately, Ben had a plan. Governor Keith had taken a liking to him (as so many people did), and the governor offered to set him up with his own print shop. He sent Ben to London to buy a press and the other supplies needed.

Deborah’s mom said that sounds very fine, and you can get married when you get back.

Things Go Wrong

We have no idea what Deborah thought or felt, but Ben was excited. Off he went to the big city, where he found to his dismay that Governor Keith was much better at making promises than at keeping them. The letters and money that Keith had supposedly left with the ship’s captain did not exist. Ben didn’t have the money to buy anything, not even a ticket home (Franklin, chapter 6). There was nothing for it but to stay and get a job, which he did. He also enjoyed himself hugely.

And Deborah? Well, her heart was probably breaking. Ben was young and thoughtless. He fully admits he more or less forgot her, saying that “I never wrote [Deborah] more than one letter, and that was to let her know I was not likely soon to return.” However, he, writing as a middle-aged man, did admit that “this was another great errata of my life, which I should wish to correct if I were to live it over again” (Franklin, chapter 6).

But that was no comfort to Deborah now. Her father had died, and her mother struggled to pay the bills. A girl in Deborah’s situation needed to get married. She could not afford not to. So, whether her heart was breaking or not, she accepted new suitors, and on August 5, 1725, she married John Rogers, an English potter. (Stuart, 15).

It turned out to be a poor choice. Deborah soon discovered that Rogers had debts he had forgotten to mention. He also forgot to mention that he already had a wife and child back in England.

Angry, embarrassed, and disillusioned, Deborah moved back in with her mother.

She was truly in a legal fix now. If this English wife really existed, then Deborah’s marriage was invalid, and she was free. But she could not prove he had a wife already. Rogers scooted off to the West Indies, and some said he died there. If so, then Deborah was a widow and she was free to marry again, but she might be held liable for Rogers’s debts. But she couldn’t get proof of death either. If he was still alive, then she was still married, and she could not get a divorce. Desertion was not one of the legal grounds for a divorce, and as for irreconcilable differences? Don’t make me laugh.

So it was that after eighteen months in London, Ben finally returned to Philadelphia, and he found Deborah living in the same house he had left her, but now she was “generally dejected, seldom cheerful, and avoid[ing] company” (Franklin, chapter 8).

At least Ben had the decency to feel guilty.

The Marriage

The good news is that even though the law had no mercy here, society did. People knew stuff like this happens, and it was unfair to hold Deborah permanently responsible. And that is how in September 1730, Deborah finally married her Benjamin, in what was known as a common-law marriage. A common-law marriage meant the church and the law were uninvolved. The couple just started cohabiting. And that was fine. They considered themselves married, and so did everyone else. As time went by and Rogers did not reappear to cause trouble, the new marriage was fully accepted as a genuine marriage, just as valid as if it had been done differently.

The person who did appear to cause trouble was a baby, named William or Billy. I say trouble because he wasn’t Deborah’s baby, but he was Ben’s. Ben never named the mother. Ever. All he says is that William was the “great inconvenience” that came as a result of consorting with “low women” (Isaacson, 76).

There is no explanation of how Ben came to have sole custody. Historians have spilled many, many words sleuthing out the possible scenarios, with zero conclusions.

There is also a general assumption that Deborah was shocked, hurt, and resentful (Stuart, 25-29). This is pure conjecture based on how a modern wife would probably feel. We have no idea what Deborah felt. She may well have known about Billy before she married Ben. It might have been part of the deal. All the primary sources I have found attesting to sharp comments by Deborah against Billy are from years and years later, when he was at an age where any parent or step-parent might be a little frustrated with their offspring. I don’t think it’s proof that she resented his existence from the getgo.

All we know for sure is that Ben accepted responsibility for his son, and Deborah acted as mother, starting about six months into her marriage (Isaacson, 75-78).

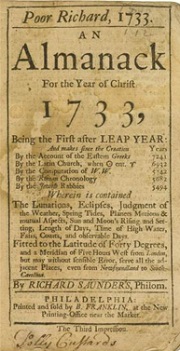

By now Ben had found a partner with enough capital to set up a print shop of their own. Deborah was, of course, responsible for the house and the child, but she was also a working woman. She kept a store, and she managed the bookkeeping herself. Some of her account sheets still exist. One of the items she sold was the first edition of Poor Richards’ Almanack at 3 shillings each. Over many editions, it was the source of most of Ben’s quotes that are still remembered today, like “early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise” or “fish and visitors stink in three days”. People loved the Almanac. It sold like hotcakes. Things were looking up for the Franklins.

In 1732, Deborah gave birth to a son named Franky. As usual, we have nothing of her thoughts on the subject, either when he was born or four years later when tragedy struck.

Up util very recent history, one of the sureties of life was that every so often smallpox would come around and devastate your community with an average 30% fatality rate (NLM). The Franklins knew this, and they also knew that the best thing you could do to protect your family was to have them inoculated, which at the time meant deliberately infecting yourself with scabs from someone who’d had a mild version of the disease. Not pleasant and not risk-free, but much, much better than waiting for a 30% fatality rate which was sure to come around. Ben was a very vocal advocate for inoculation.

But inoculation wasn’t permanently available. As you can imagine, you didn’t always have someone on hand with the necessary scabs. Little Franky missed his chance to be inoculated because he was already sick with dysentery when the option existed. So he was unprotected when smallpox came around again, and he died of it.

Deborah’s grief is not recorded. In his Autobiography, Ben recorded his grief, saying “I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen” (Stuart, 35; Franklin, chapter 10).

The Partnership

With growing businesses and civic responsibilities, Ben was now traveling around Pennsylvania and sometimes farther afield, which might have left his local businesses in a quandary. In 1733, Ben fixed that by giving Deborah formal power of attorney to act for him. It was not uncommon for wives to act as partners in their husbands’ businesses. But ordinarily it was all done in an unrecognized, informal way. Ben’s power of attorney signified that he fully trusted Deborah to make sound business decisions in his absence, and he wanted to make sure everyone else treated her accordingly.

Ben was an intelligent man. Is it likely he would have done that if his wife had been as unintelligent as early historians asserted? He trusted her, and she did just fine in his absence. Ben himself said as much in print. In 1735, an anonymous letter to the editor asserted that marriage was nothing but slavery for a man and every woman was a tyrant. Not so, Ben published in response:

“I and thousands more know very well that we could never thrive till we were married; and have done well ever since; What we get, the women save; a man being fixed in life minds his business better and more steadily … the idleness and negligence of men is more frequently fatal to families than the extravagance of women. Nor does a man lose his liberty but increase[s] it … having a wife, that he can confide in, he may with much more freedom be abroad, and for a longer time; thus the business goes on comfortably, and the good couple relieve one another by turns, like a faithful pair of doves” (Stuart, 37).

In 1737 Ben was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia. Unlike today, postage was not so simple as sticking on a stamp. The postmaster had to send out bills, sometimes negotiating multiple international currencies to do so. Deborah handled this, and she did so successfully (Stuart, 38). Again, I would ask: is this kind of mathematical calculation the work of an uneducated woman? Even today, most of us just whip out a calculator.

On a more personal note, Deborah gave birth to her second child eleven long years after the birth of her first. They named the little girl Sally. Ben did not publish on the subject of why it took so long, but the most likely scenario is multiple miscarriages.

By now Ben was a far cry from the plucky runaway apprentice. He exemplified the American success story: he had pulled himself up by the bootstraps with a combination of hard work and raw talent. And his wife had done with him.

Being now a rich man, he could spend time on other pursuits, like experiments with electricity, and inventing a new kind of stove, and advising a constant stream of admirers (Stuart, 43).

A Diplomat for Pennsylvania

The Franklin marriage worked well enough until 1757 when the Pennsylvania legislature asked Ben to go to England and negotiate with the Penn family who still held large tracts of land in Pennsylvania and did not pay taxes.

Ben was honored and delighted with the commission. Deborah said she didn’t want to go. As per usual, we don’t get any direct words from her stating why. There are much later third-hand comments from other people saying that she was afraid of ocean travel. Historians use this as ammunition against her. Obviously, they say, she was timid and unadventurous. What I think is obvious is that these are largely people who haven’t experienced seasickness without the benefit of modern remedies.

Even the kinder historians generally fail to realize that there were other reasons for Deborah not to want to go. She had a life in Philadelphia: a store, a post office, a church, friends, family. I live in a world where a decision to abandon all that and move across the ocean ought to be a joint decision between both spouses. I know because that’s what it was when my husband and I did exactly that.

It’s impossible to know whether there was anything joint about the Franklin decision, but the results are clear: Ben went. Deborah stayed.

Ben had a grand time in London. He didn’t make much progress with the Penns. None, in fact. But he certainly enjoyed himself. In particular, he liked his landlady, a widow named Margaret Stevenson. He liked her so well that his new friends noticed. One of them took it upon himself to write to Deborah, a woman he had never met, on the subject:

“For my own part, I never saw a man who was, in every respect, so perfectly agreeable … Now madam as I know the ladies here consider him in exactly the same light I do, I think you should come over, with all convenient speed to look after your interest; not but that I think him as faithful…as any man breathing, but who knows what repeated and strong temptation, may in time, and while he is at so great a distance from you accomplish” (Stuart, 72).

We have absolutely no hint of what Deborah thought when she read this: hurt? disbelieving? indignant?

All we know for sure is that she did not sail for England.

The friend’s motivations are unclear. It might have been malicious, but that does not mean his implications were untrue. On the contrary, Ben and Margaret were increasingly seen parading around town as if they were a couple.

Meanwhile, Deborah managed all the various businesses and raised Sally alone and wondered when Ben would come back. He occasionally wrote that he would return soon. But the word “soon” didn’t seem to mean much to him (Stuart, 80). One of the ironies of Ben’s story is that as the quintessential American, he clearly preferred living in England.

It was five years before he reappeared in Philadelphia, without giving warning. Sally had grown up into a young woman in his absence. Billy seemed to think that things were now settled. wrote that “My mother is so entirely averse to going to sea, that I believe my father will never be induced to see England again. He is now building a house” (Stuart, 88).

But Billy was wrong.

A Diplomat for the Colonies

In 1764, the legislature appointed Ben as their agent and sent him back to England. He had only been home for two years. Again, Deborah refused to go. Again, Ben went without her. He moved right back in with Margaret and delightedly reunited with all his friends. The only thing that was different is that this time, Deborah’s letters to him have survived. She was somewhere in the neighborhood of age 60, and this is the first time we get any words of hers, other than lists of accounts for the store. Deborah wished Ben well and gave details of how she was getting on with the building of the house, a project she was now fully in charge of (Stuart, 96). She and Margaret also wrote to each other, which seems a little odd to me. You’d expect their relations to be strained, but there was plenty of exchanging of presents.

While Ben was enjoying himself, it was true that once again his official purpose for being there didn’t go well. Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which was a significant new tax on colonists. Ben was supposed to be preventing stuff like that. What else had the colonists sent him to England for?

Ben was safe in England, but as local anger began to rise, Deborah’s friends began to worry that if colonists could not take out their anger on Ben, they would settle for doing so on his nearest and dearest. She was advised to leave town.

Deborah was a woman who knew her own mind. If Ben and Europe could not entice her away from her home, she certainly wasn’t going to be driven out. She asked several of her male relatives to come and bring their guns with them. They did, and Deborah herself spent the night standing watch, fully armed. A mob did gather, but so did 800 supporters. Deborah was fine.

Ben took little notice of his wife’s difficulties. He was meeting with Parliament members night and day, and the Stamp Act was repealed. A victory, but an exceptionally brief one. There were more taxes to come.

Meanwhile, Deborah had more personal battles. Sally wanted to get married. Richard Bache, the man of her dreams, was a merchant and he was heavily in debt. Deborah did not like this, and Ben was outright horrified. But he wasn’t there. Deborah was a little exasperated about handling it on her own. She wrote to Ben that “I am obliged to be both father and mother,” which was a little hint. She did not feel she could forbid Sally to see Richard, for it would “only drive her to see him somewhere else” (Stuart, 102).

Sally married her Mr. Bache and had two children, but still Ben did not come home. Deborah wrote him newsy letters about the grandchildren and sent barrels of Pennsylvania’s finest products: buckwheat, cornmeal, apples, and dried peaches. Even two live squirrels for the amusement of his friends (Stuart, 113).

And finally she sent him increasingly frequent reminders that she would like him to come home. The years were passing, and her own health was failing.

Finally, she stopped writing to him at all.

On December 14, 1774, Deborah suffered a stroke and died. She had not seen her husband for over ten years.

Billy wrote the news to his father:

“I came here on Thursday last to attend the funeral of my poor old mother who died the Monday noon … She [earlier] told me that she never expected to see you unless you returned this winter, for she was sure she would not live till next summer. I heartily wish you had happened to come over in the fall, as I think the disappointment in that respect preyed a good deal on her spirits” (Stuart, 119).

I don’t know what Ben thought when he read this. But I hope he felt at least a smidgen of regret.

Overall, even the writers who try to be kind to Deborah manage to portray her as a faintly pathetic figure. One of them says bluntly that her decision not to go to Europe was a very bad mistake (Stuart, 65).

I’m not so sure that it was. Or at least that Deborah thought it was. At any point, she could have hopped a boat and joined Ben in England. She had the funds and the invitation. She just chose not to. And if what we see of her is largely her unfulfilled wishes for Ben to come home, well, that is because that is the only part of her life where her words are preserved. Everyone’s life is a tragedy if you look only at the end. If you look at her life in total, you can see a loving wife and mother and an accomplished businesswoman. It’s in no way pathetic.

As for Ben, he returned to America five months after his wife died. War was now inevitable. His next move to Europe wasn’t to England. It was to France to ask for military aid. He was considerably more successful at his mission there.

Selected Sources

Brands, H W. The First American : The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. New York, Anchor Books, 2002.

Bunker, Nick. Young Benjamin Franklin : The Birth of Ingenuity. New York, Vintage Books, 2019.

Franklin, Benjamin . “The Project Gutenberg EBook of “Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.”” Gutenberg.org, 2019, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm.

Isaacson, Walter. Benjamin Franklin : An American Life. New York, Simon & Schuster, 2004.

National Library of Medicine. “Smallpox: Variolation.” Www.nlm.nih.gov, 5 Mar. 2024, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/smallpox/sp_variolation.html?lang=en.

Roberts, Cokie. Founding Mothers : The Women Who Raised Our Nation. New York, Perennial, 2005.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. Poor Richard’s Women : Deborah Read Franklin and the Other Women behind the Founding Father. Boston, Beacon Press, 2022.

I loved this. It fit exactly with how Ben is portrayed in the musical 1776. And I love your insights on whether an entire life is a failure. Thanks, friend, for teaching me NEW things about history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank YOU for all your listening and support!

LikeLike

[…] complicated than we would like. On my show alone, there’s been Gandhi and Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin and others. But if this was Martin Luther King Jr’s personal failing, then I will say this for […]

LikeLike

[…] there’s no denying that the wives of the American Founding Fathers were incredible, and at the top of the list is usually Abigail Adams. She was intelligent, […]

LikeLike

[…] about whether this was a good idea, but two who sincerely regretted not doing it were Benjamin and Deborah Franklin (episode 14.7). Their son Franky died of smallpox, and Ben would later write […]

LikeLike