Note: If you prefer to read my posts instead of listen, this transcript is here for you as usual. But this time listening comes with a soundtrack, so it might be time to make an exception…

Even if you do not consider yourself a classical music expert, you have heard Mozart’s music. He wrote a bevy of greatest hits that have featured in I don’t know how many movies, ranging from string quartets like the Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, to piano solos like the Rondo alla Turca, to symphonies like #40, and many, many, more.

As an 18th century composer, Wolfgang lived well before recording equipment, which is a real shame because he was the quintessential child prodigy. He performed for European royalty at the tender age of six.

But he wasn’t the only child prodigy in his family or even the first. He had a role model for inspiration. Big sister Nannerl led the way.

The Mozart Family

The two Mozart prodigies were the children of Leopold Mozart and his wife Maria Anna. Leopold was an on-staff musician in the court of Salzburg, which is now part of Austria, but borders were different then. In the 18ᵗʰ century, a musician was a servant, pure and simple. A skilled servant, yes, but no more so than the servant who cooks your food, sews your dresses, or drives your carriage.

Leopold got a small salary as a court musician, but he supplemented it by giving public concerts, teaching, and also by marketing a book he wrote on how to play the violin.

The Mozarts had seven children, but five of them died infancy. Statistics like that are plenty common in history, but I always like to say it a little louder because while we are grousing about the state of our world we live in, we sometimes overlook just how much better some aspects of life have become. Nannerl was baby #4, born on July 30, 1751. They named her after her mother, but she was nicknamed Nannerl and that is how I will refer to her. Baby #7 was born in 1756, and they named him Wolfgang.

We have no information on their earliest years, but as Leopold was a musician and teacher himself, it was only natural that they should be hearing music from day one. But it was not until Nannerl’s 8ᵗʰ name day, or July 26, 1759, that Leopold gave her a book of sheet music and began formally teaching her to play the keyboard.

in this episode I’m going to say keyboard, because the instrument in question might be a piano, but it also might be a harpsichord or a clavichord. These were all played by pressing the keys on a keyboard, and it’s not always totally clear which one an 18ᵗʰ century musician is talking about.

Nannerl did very, very well on her keyboard, and Leopold was delighted.

If you have kids, you’ll know that it was entirely predictable that little three-year-old Wolfgang would watch this and think he was fully capable of participating too. The desire to be like the big kids is a powerful motivator. It certainly worked on me.

The unpredictable bit was that Leopold said, yeah, okay, let’s do this, instead of you’re too young, wait until you’re older, or wife, come get the little one out of the way.

So Wolfgang got lessons at the age of three. It is hard to overstress how revolutionary this was. Nowadays, if you’re in the classical music world, you know that very, very young children can be taught music, especially with the Suzuki method. (I was a Suzuki child myself, starting at age three, but not a prodigy, alas.)

Making this work requires an extraordinary commitment from the parents. You can’t just tell a 3-year-old (or even most 8-year-olds) to go practice for an hour and expect anything musical to come out of it. You have to go spend that hour with them. It helps to be a gifted musician and (more importantly) a gifted educator, as Leopold undoubtedly was.

Maria Anna is given little to no credit in this education process, but I’m 99% certain that’s an omission in the record, not in her actions. Nannerl and Wolfgang were entirely homeschooled, yet they turned out both highly musical and literate in multiple languages. Do you think mom was uninvolved? I don’t think so.

The Prodigies on Tour

Leopold was so pleased with his kids that in 1762 he took them to Munich so he could show them off to the prince of Bavaria. Nannerl was ten; Wolfgang was six. They were both adorable and accomplished. Munich proved good and so they went to Vienna, where they played for the empress Maria Theresa. It is on this visit, that Wolfgang supposedly met princess Marie Antoinette and declared he would marry her (Rushton, 8; Johnson, 9, 10) but it’s probably not true (Timms).

Newspaper reports at home and abroad praised Nannerl for her mastery of the most difficult pieces available (Halliwell, 41). But the letters Leopold wrote to friends were mostly about Wolfgang.

And why wouldn’t they be? Wolfgang was the one who would grow up to have a glittering career and support his parents in his old age. As a girl, the days of Nannerl’s career were already numbered.

But they weren’t over yet. In 1763, the Mozarts left home for a tour that would last three and a half years. If you’ve ever tried to help a small child practice daily, imagine doing it while constantly on the road. The mind boggles, but the Mozart parents managed it. They bought an instrument designed for travel, and the lessons went on as they performed their way through Germany and France (Mozart, volume 1, 39).

Many a historian has assumed that because Leopold (and the newspapers) took so much notice of Wolfgang that Nannerl must have resented it. As per usual, we have no idea what Nannerl thought, but I don’t think resentment is necessarily a given.

There is only one piece of evidence that suggests sibling rivalry might have been a problem, rather than a motivation to them both. This evidence is a comment Leopold wrote in a letter to a friend on August 20, 1763, while they were staying in Frankfurt. Leopold wrote “Nannerl no longer suffers by comparison with the boy, for she plays so beautifully that everyone is talking about her and admiring her execution” (Mozart, volume 1, 39; Halliwell, 56).

Whether Leopold was right in his assessment is another issue altogether, and we have no way of knowing.

From Paris, the family went to England. At some point along the way, Nannerl began keeping a diary, which is initially very exciting for historians, but somewhat less exciting once you get in and read it. It is not a deep dive into the thoughts and relationships of a young girl. It’s more like a calendar of appointments, listing what she did on a particular day (like giving a concert), but without any details (like what they played, or how it went, or whether she enjoyed it, or what the audience said).

But it is a lot better than nothing, and there are occasional glimpses of her mind at work, such as her comment on seeing the English Channel in Calais, where she wrote, “I saw how the sea runs away and advances again” (Halliwell, 65). Or on sightseeing in London where she wrote, “I saw the park and a young elephant, a donkey that has white and coffee-brown stripes, and so even that no one could paint them better” (Halliwell, 89). I’m guessing this was a zebra? Not a familiar animal to her.

It wasn’t all vacation, though, especially not for Leopold. It was no joke to travel to a foreign country with a family in tow and make it pay for itself. He was constantly worried about money and the patronage was difficult. Then he fell dangerously ill in London, which must have terrified them all. Neither the kids nor Maria Anna could have arranged all these performances. No one would have given them the time of day. Financial worries would continue to plague Leopold for the rest of his life.

In 1765, the Mozarts left London with the intent of going home. It took them sixteen months to get there, partly because of detours for concerts, but also because in the Hague, Nannerl grew so ill they despaired of her life and had a priest give her extreme unction. She lived, but she needed round-the-clock care for six weeks, and then Wolfgang got sick too.

They were home for only a brief while before they took another tour to Vienna. This was to be Nannerl’s last tour because the trouble with being a child prodigy is that the older you get, the less you are a sensation. Your abilities may grow (or at least stay the same), but you’re no longer so cute while you do your thing. At age fifteen, Nannerl was considered nearly marriageable. It was time to stop performing for royalty and get herself a man.

Left Behind

When the next tour opportunity came around, Leopold took Wolfgang to Italy. He left Nannerl and her mother at home.

The good news is that the family wrote letters to each other. The bad news is that only the letters from the menfolk survive, so we get only half the conversation.

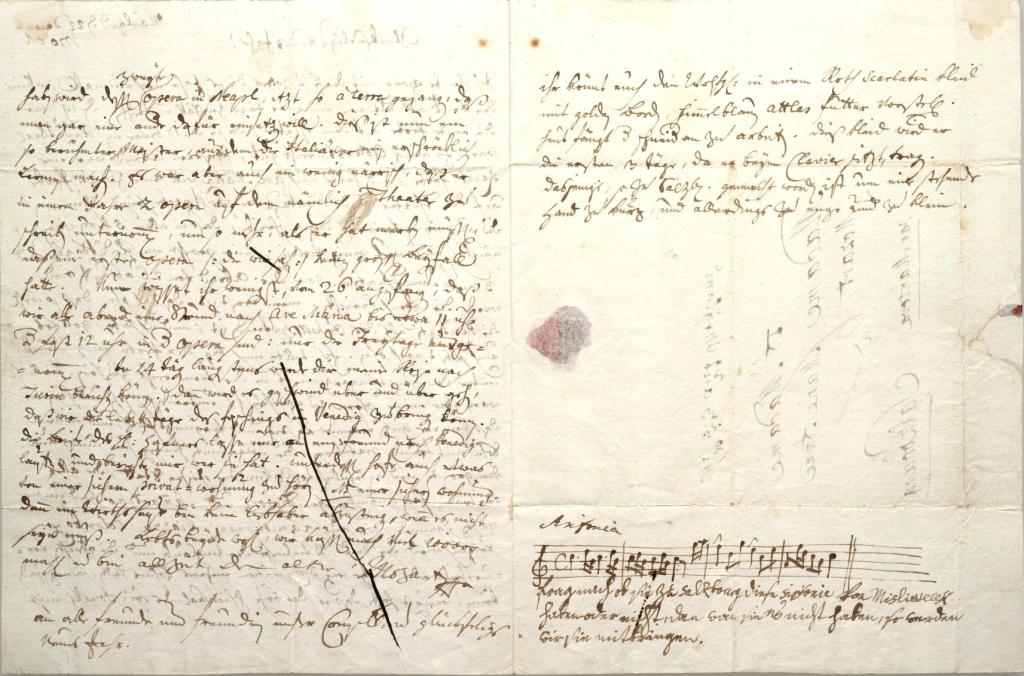

This is particularly unfortunate because of two comments made by Wolfgang. He thanked Nannerl for sending him her keyboard arrangement of a minuet by Haydn, which he thought she did very well. And later she evidently sent him the original score of a song she composed from scratch because he wrote “I am amazed to find how well you can compose. In a word, the song is beautiful. Try this more often” (Mozart, volume 1, 218; Halliwell, 158).

I’m not sure why Wolfgang should have been so surprised that Nannerl could compose, except that girls weren’t expected to compose. Wolfgang had been encouraged to do so from the age of four. So it’s a double tragedy: first that Nannerl wasn’t encouraged earlier and second that her song doesn’t survive, and nor does any other composition by her. In contrast, Wolfgang was always sending her keyboard music he had written with her in mind. Or even if he wrote them with himself in mind, she was the next to get the score. He would do this for the rest of his life, and mostly his scores have survived.

Throughout this trip (and other trips to come), we can infer that Nannerl and her mother wanted to join in the traveling. Though we don’t have their letters saying so, we do have Leopold’s repeated explanations as to why they could not: it was always either too expensive, or too hot, or too cold, or (interestingly), would arouse suspicion.

This last excuse is a little puzzling but becomes clearer in 1777. Leopold was technically still on staff as a court musician in Salzburg. As you can imagine his employers were getting a little tired of his constantly being absent. They suspected that Leopold was trying to get a more lucrative position elsewhere, either for himself or his son. The suspicion was warranted because that’s exactly what he was trying to do.

By 1777, the situation could be sustained no longer. It was either lose the Salzburg job or stay in town and do the job. Since that salary was the only steady income the family had, Leopold reluctantly stayed in town and sent his wife to Paris with Wolfgang. Nannerl still didn’t get to go.

At this parting, both Leopold and Nannerl were so upset that they went back to bed for the rest of the day (Halliwell, 239).

At Home in Salzburg

By one way of thinking, however, this was not all bad for Nannerl. With Leopold at home and Wolfgang away, Leopold doted on her instead. Prior to this point, her keyboard instruction had focused on solo performance (or duets with Wolfgang). But keyboard playing is not just one skill, it is many skills. Her training had not included accompanying, sight reading, figured bass, or improvising. These were skills needed by Kapellmeisters (or leaders of ensembles). As a girl, she could never get a job as a Kapellmeister, so why learn the skills?

But now that Leopold had time on his hands, he did teach her. By April 6, 1778, he boasted that she could accompany as well as any Kapellmeister in Europe (Halliwell, 250).

We can be sure that this was not just parental bragging. Nannerl’s diary and the family letters make it clear that the Mozarts were having their musical friends visit almost daily on social calls. Together they played cards and they went shooting, but they also played orchestral works. Since they rarely had a full orchestra present, Nannerl read the music from a full score and single-handedly supplied all the missing parts from the keyboard (Halliwell, 255). This no trivial skill. It’s the kind of thing that theater and choir accompanists learn, but it is not taught in your run-of-the-mill piano lessons even today.

You may have noticed that the purpose of Nannerl not touring anymore was because she was supposed to get married and yet I have not so much as mentioned a suitor. This was on Leopold’s mind too. He was feeling his age, and since he had largely sacrificed his opportunities for career advancement by focusing on his children, he regularly reminded Wolfgang of the importance of Wolfgang getting a steady court appointment soon. Because if he didn’t, and Leopold died, then Nannerl would be forced into domestic service and Maria Anna would be destitute (Mozart, volume 2, 733).

Wolfgang did not seem to appreciate this argument very much. He did not seem to be taking the necessary steps to get such an employment (Mozart, volume 2, 828). Frustration was high on all sides

In July 1778, Leopold and Nannerl got a letter with terrible news. It wasn’t Leopold who died. It was Maria Anna (Mozart, volume 2, 830). Grief hit hard.

Ultimately, Wolfgang ended up in Vienna, still without a court appointment. Nannerl started having health problems, but she also found herself a suitor. His name is Franz Armand d’Ippold. It is unclear why they didn’t marry, but money was probably at the heart of it. Wolfgang tried to be helpful. He quite seriously told Nannerl that the best cure for her health problems was to get married. He suggested they should all come to Vienna. He could freelance, d’Ippold could get a job, Nannerl could teach and give concerts, Leopold could retire, and they could all four live happily ever after on three incomes (Mozart, volume 3, 1141-1142).

This was pure fantasy. Leopold and Nannerl knew full well that Wolfgang was having trouble supporting even himself in Vienna. If Nannerl married, she would likely enter an endless pregnancy cycle which would be good for neither her health nor her career opportunities, and what kind of job was d’Ippold supposed to get? He had a position in Salzburg. These things were not transferable.

Then there was the question of Wolfgang’s own marriage. Leopold warned him that a wife would be the absolute worst financial decision he could possibly make, but Wolfgang got married anyway. The prospect of him supporting his father and sister grew still more remote. Leopold and Nannerl stayed in Salzburg where they at least had a chance to make ends meet.

Marriage at Last

In 1784, Nannerl finally got married. She was 33 years old, and it was a mere eighteen years since she was told to give up her profession so she could get married. The lucky groom was Johann Baptist Berchtold von Sonnenburg. He had been married twice already and there were five children to look after. He also lived in the small village of St Gilgen, a six-hour journey east of Salzburg. Nannerl called it a wilderness (Halliwell, 455).

You may have felt (as I did) somewhat miffed that Nannerl got short-changed in comparison with Wolfgang and there’s truth to that. But in comparison with many children, both girls and boys, Nannerl had been unbelievably lucky, and she would soon come to know it. Leopold had his faults as a father, but he was at least interested in his children and their education. Also, Maria Anna had been a constant source of security for many years.

The five Berchtold children had grown up in a small village without much of a school, with a father who had no interest in home schooling, and a rotating cast of mothers, stepmothers, and servants. To be more blunt, these kids were practically illiterate, unhygienic, and badly behaved (Halliwell, 458). They were certainly not musical, and nor was anyone else in St Gilgen. Leopold gave Nannerl a piano for her wedding. But it went out of tune immediately on arrival and there was no one in St Gilgen who could fix it. After a cold winter there, the keys stuck, and it was utterly unplayable (Halliwell, 474)

When Nannerl was pregnant herself, she returned home to Salzburg for the delivery and when she went back to St Gilgen, she left her little Leopold with his grandfather. This is sometimes portrayed as Leopold being domineering and demanding she give up her baby to him. It may have been. We don’t have Nannerl’s thoughts on the subject, but we do know she despaired of raising the other five children well (Halliwell, 488). So this may have been her idea, as the best she could do for her own son.

Nannerl and Leopold continued to correspond with each other (and with Wolfgang) until Leopold’s death in 1787. Wolfgang did not come when Leopold was sick (though he was asked), and he did not come afterwards either. He took no goods from the estate either (though he was offered some). He only wanted cash (Halliwell, 564). I don’t really think Mozart was heartless, but he was financially strapped.

In the final twist of irony, it was after Leopold’s death that his dearest wish came true: Wolfgang finally achieved a court appointment. Since Nannerl was now married anyway, it did her no good.

The Final Years

Unfortunately for us, the sources now thin out because letters to and from Leopold had always formed most of the base material. The sources get fewer still after Wolfgang’s untimely death only a few years later in 1791.

But we do know that when Nannerl’s husband died, she moved back to Salzburg, where she taught lessons and performed. She was a consultant for the first person to write a biography of her brother, and she loyally tried hard to avoid saying anything negative about him. The writer took a negative slant anyway.

She also helped publishers compile various editions of Wolfgang’s manuscripts and this is not a trivial consideration. Being a genius composer is one thing, but if no one publishes the manuscripts posterity will never know. In some cases, Nannerl had a more complete manuscript than anyone else because Mozart tended to perform parts of his works as improvisations. It was she who had begged him to write out the cadenzas for her (Mozart, volume 3, 1248, for one example).

So in the end Nannerl was behind Wolfgang from the very beginning as a role model and a partner. She was still behind him at the very end as a publisher and biographer. She lived in until 1829, thirty-eight years longer than her younger brother.

Like the Mozarts, I too am doing this podcast gig as a freelancer, without a royal patron. If you can find it in your hearts to contribute to the cause, please head to my Patreon page, make a one-time donation on Buy Me a Coffee, or check out the merch on the store, and I will be very grateful. Next week I will stick with the music theme and head to a very different composer. Tchaikovsky also owed his success to a woman, but she wasn’t his sister.

Selected Sources

Halliwell, Ruth. The Mozart Family : Four Lives in a Social Context. Oxford England ; New York, Clarendon Press, 1998.

Johnson, Paul. Mozart : A Life. London, Penguin, 2013.

Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus, and Leopold Mozart. The Letters of Mozart and His Family. Translated by Emily Anderson, vol. 1-3, London Macmillan, 1985.

Rushton, Julian. Mozart. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Timms, Elizabeth Jane. “When Mozart Met Marie Antoinette?” Royal Central, 5 July 2020, royalcentral.co.uk/features/when-mozart-met-marie-antoinette-133508/.

[…] had plans for his little girl. He intended her to become a piano virtuoso, much in the way that Nannerl and Wolfgang Mozart had been decades earlier. It’s a little surprising that Wieck had this goal. Partly because […]

LikeLike

[…] Tofana became the secret fear of men for generations. Most famously, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worried that he had been given Aqua Tofana during his final illness. It is generally believed that […]

LikeLike