In case your knowledge of classical music is rusty, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is among the most popular composers of the 19ᵗʰ century. He wrote the Nutcracker, the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture, the Sleeping Beauty theme Disney would copy, and much, much more.

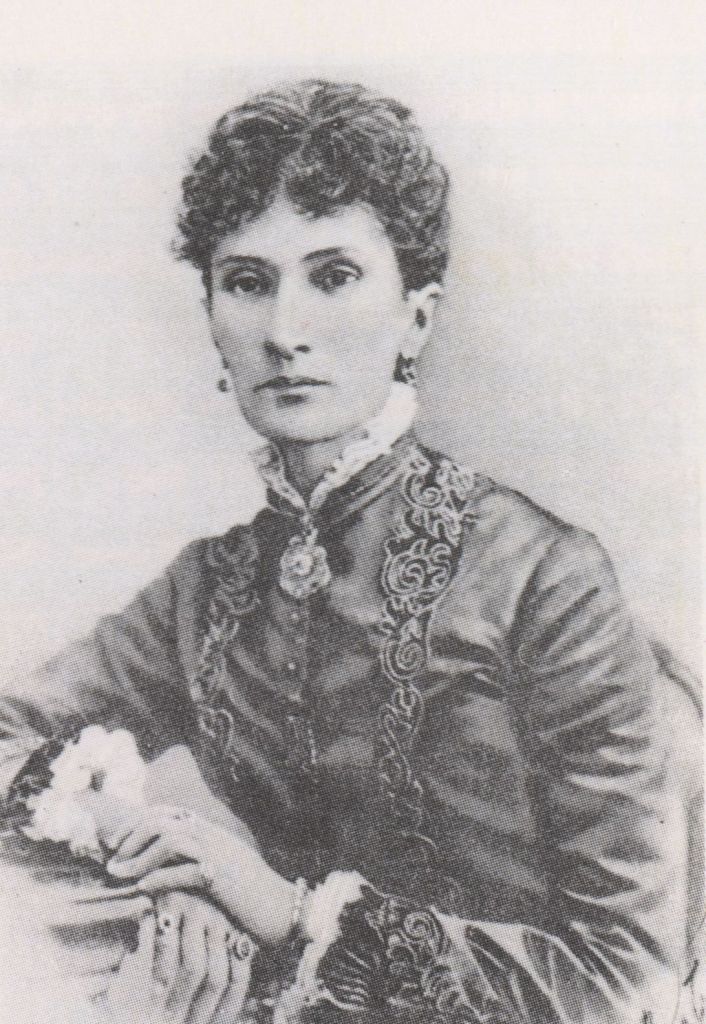

He also had the very strangest of all the relationships I have described in this series, and maybe on this podcast. 100% of my sources were more interested in him than they were in his friend, Nadezhda von Meck, which means my knowledge of her first 45 years is sketchier than I would like, but here’s what we can do.

Riches to Rags to Riches

Nadezhda was born in 1831 to wealthy Russian parents who gave her the education expected for a girl of her social status: a little literature, a little history, multiple languages, and piano lessons. No career plan except marriage, and she accomplished that at the ripe age of seventeen.

The lucky groom was Karl Otto von Meck. I would like to say it was a happy marriage, and I have no absolute proof otherwise, but the circumstantial evidence is not encouraging. Nadezhda was later to write “It is a pity that one cannot cultivate human beings artificially like fishes; people would not then need to marry, and it would be a great relief” (Bowen, 32).

Nadezhda was very good at cultivating human beings the normal way: she had 13 children, and 11 of them survived. Historically speaking that’s a very good rate of return, but I can only imagine that it took a toll, physically at the least, and probably emotionally too because Nadezhda was unable to provide the kind of upbringing she had enjoyed herself. Karl was an engineer with a badly paid government position and no prospects for promotion. Nadezhda had to be mother, governess, nurse, dressmaker, and housekeeper all in one. While she was certainly not alone doing that, please remember that it was a lot more work with no household appliances or public schooling options (see series 7, which starts here). Nadezhda herself could do nothing to change the financial situation because she’s just a woman, remember?

It did not escape her notice that her husband was an engineer, and their native Russia was seriously behind the rest of Europe in railroad construction. Karl wasn’t super interested in quitting a small but steady government salary in favor of gambling on a new and uncertain industry. But eventually Nadezhda nagged him into it, and she was right. Within a few years, Karl owned several new railroad lines, including the ones that transported grain from Russia’s grain belt to their major population centers. Then Karl up and died, leaving Nadezhda as the only type of woman who had significant autonomy in this time period: a very wealthy widow (Suchet, 149-150).

A Patron of Music

Nadezhda continued to raise the children, but she withdrew from social engagements. She didn’t want to meet people and mingle, and the privilege of wealth is that you don’t have to be normal if you don’t want to. Even when her children got married, she refused to attend and never met the in-laws.

What she did do was go to concerts. She had always loved music and now she had the money to indulge in it. Among other things, she made donations to the Moscow Conservatory. The head of the Conservatory was Nikolay Rubinstein, and through him she heard of one of his professors: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Tchaikovsky was earning his living by teaching at this point, but only because the freelance creator gig is not very lucrative. (Ask me how I know?)

Anyway, he had already written some of his greatest hits: Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake, the 1ˢᵗ piano concerto, the Marche Slav, and more. So there was plenty for Nadezhda to admire when she sent a message offering to pay him a commission if he would arrange some of his pieces for piano and violin.

Tchaikovsky accepted her offer and whipped out the arrangements in record time. On December 30, 1876, Nadezhda wrote him the first of many surviving letters. It said:

“Permit me to express sincere thanks for the speedy execution of my commission. To tell you into what ecstasies your composition sent me would be unnecessary and unfitting, because you are accustomed to the compliments and homage of those much better qualified to speak than a creature so musically insignificant as I. It would only make you smile. I have experienced so precious a delight that I could not bear to have anyone find it ridiculous, so I shall content myself with asking you to believe absolutely that your music makes my life easier and pleasanter to live” (Bowen, 30; Tchaikovsky, 209)

Nadezhda probably did not imagine that to future generations, it wasn’t her musical taste that was ridiculous, but her obsequiousness and exaggerated humility. It was a very exaggerated age.

For Tchaikovsky, this was the very best kind of fan letter because it came attached to a substantial payment. The first of his many surviving letters to Nadezhda says:

“I am sincerely grateful for the kind and flattering words that you were good enough to write me. To a musician, with all the disappointments and failures that obstruct his path, it is a comfort to know there is a small minority of people like yourself who truly and warmly love our art” (Bowen, 30).

Very polite, but it does have a whiff of the form letter about it. Tchaikovsky probably assumed the business arrangement was over, but two months later, Nadezhda wrote him again with another commission offer and a note that said:

“I should like very much to tell you at length of my fancies and thoughts about you, but I fear to take your time, of which you have so little to spare. Let me say only that my feeling for you is a thing of the spirit and very dear to me. So, if you will, Pyotr Ilyich, call me erratic, perhaps even crazy, but do not laugh—it could be funny if it were not so sincere and real” (Bowen, 30; Tchaikovsky, 209-210).

In modern parlance, I don’t think crazy is the right word. Creepy is more like it. But Tchaikovsky didn’t feel that way. He was as lonely as she was, so he accepted her opening gambit. He took the commission and said “I am sorry you did not tell me all that was in your heart. I can assure you it would have been very pleasant and interesting, for I, too, warmly reciprocate your sympathy. This is no empty phrase. Perhaps I know you better than you imagine” (Tchaikovsky, 210; Bowen, 30).

Which is equally creepy! What did he know of her? Nothing! Why should he warmly reciprocate sympathy?

In her next letter, Nadezhda laid it all on the line. She admitted to being obsessively interested in him, but the difference between her and your average, panting, teenage fangirl is that Nadezhda was old enough to know this was ridiculous. She knew no flesh-and-blood man would measure up to her imagination. She wrote:

“There was a time when I wanted to meet you. Now, the more I am charmed, the more I fear meeting… At present I prefer to think about you at a distance, to hear you in your music and in it to feel with you” (Bowen, 66).

Thus begins a 13-year correspondence of 1200 letters between two people who shared (almost) everything with each other, but they never actually … met.

Nadezhda Rescues Tchaikovksy

This arrangement served them both very well. Nadezhda merely suspected Tchaikovsky would not live up to the pedestal she had placed him on. Tchaikovsky was absolutely certain of he would not.

Besides the ordinary human foibles that distinguish your average person from God, Pyotr had two very pronounced characteristics that Nadezhda did not know about.

First, he was utterly hopeless with money. Just one quick example out of many possibilities: Later in life Tchaikovsky was commissioned to write music for the emperor’s coronation. He thought the music was worth 1500 rubles, and he borrowed money against that amount. The emperor paid him with a gold watch and no rubles at all. A pawnshop gave him only 375 rubles for the watch. Then he lost both the 375 rubles and the pawn ticket. See what I mean by hopeless? (Wiley, 248)

Nadezhda would learn this truth about Tchaikovsky very well. Again and again she came to his aid with money. He hated how the money question complicated their relationship (Wiley, 185-186; Bowen, 71, 137). Early on he admitted that “every time I receive an envelope from you, money falls out” (Bowen, 74), but Nadezhda didn’t seem to mind. She considered it a privilege.

The other secret was the one and only thing they never discussed: Tchaikovsky was homosexual. There are some historical figures who are suspected of being LGBTQ+, but there’s room to doubt because most people would not have put a thing like that down in plain, unmistakable writing. I am mentioning this because this is not one of those cases. Tchaikovsky did put this down in unmistakable writing to several people, but Nadezhda was not one of them.

Tchaikovsky lived in fear of being found out, and he had quite recently declared his positive intention of getting married, legally, to anyone. Not because he was interested in being married. He just wanted to stop the rumor mill (Bowen, 86).

Tchaikovsky very soon did get married to a former student named Antonina. It was very brief disaster. Brief in the sense that they only even pretended it worked for a few weeks. He spent the rest of his life trying to get a divorce and never managed it.

In anguish, he explained all this in detail to Nadezhda, including the part about how he had never loved Antonina and that had explained that clearly to her in advance. Nadezhda played the role of the very supportive friend. When he wanted to be married, she sent her congratulations (Bowen, 102). Later he said that he now despised his wife and wanted to strangle her. Or himself (Bowen, 136). I mean that last one quite literally: he wrote Nadezhda about his suicide attempt. But she assured him that he had done absolutely nothing wrong (Bowen, 138). Antonina was obviously lazy, idle, and was crying only for show because she was incapable of feeling anything deeply (Bowen, 147).

This is an extremely harsh judgment on a fellow woman (whom Nadezhda had never met), but there’s no doubt that it soothed Tchaikovsky’s self-recrimination. He felt better. Also, both marriage and divorce require money, and Nadezhda was there to provide.

It was years before she admitted how she had really felt.

“Do you know that I am jealous in the most unpardonable way? Do you know when you married it was terribly hard for me, as though something had broken in my heart? … And do you know what a wicked person I am? I rejoiced when you were unhappy with her! I reproached myself for that feeling. I don’t think I betrayed myself in any way, and yet I could not destroy my feelings… I hated that woman because she did not make you happy, but I would have hated her a hundred times more if you had been happy with her… I believe it is better for you to know that I am not such an idealistic person as you think” (Bowen 342, 343).

The jealous third woman is hardly a new concept in the world but remember Nadezhda had never met the man!

If this relationship seems a little unhealthy, I’m not really arguing, and yet it’s puzzling just who was exploiting who. You could see it as a domineering woman keeping a poor and mentally ill genius dangling. You could also view it as an unscrupulous musician manipulating an older woman’s emotions for her money.

Personally, I prefer to see it as two friends, both of them struggling to navigate a world that was unfair and unequal in so many ways. It is true that Nadezhda had the advantage of having all the money and eleven children to prove she conformed to society’s sexual expectations, but Tchaikovsky had advantages too: he had a solid education and career opportunities. No one had ever offered either of those to Nadezhda.

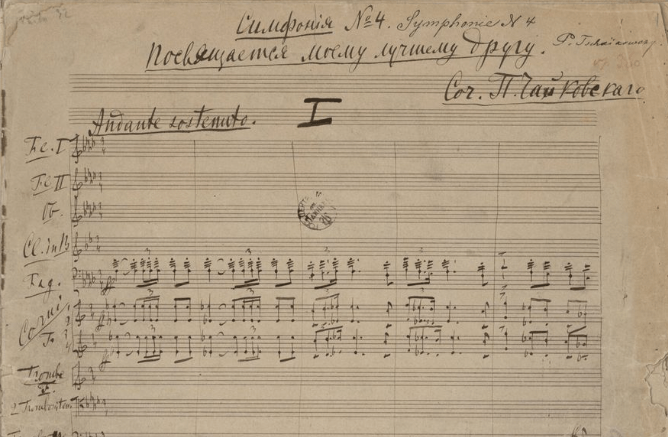

The Fourth Symphony

Together they made a success of it. Nadezhda delivered a regular and extremely generous stipend. Tchaikovsky quit his professorship and composed full time. It was a time when patron and artist were considered equal in the creative process, which is why he more than once referred to his brilliant and eternally popular 4ᵗʰ Symphony as “our symphony,” meaning his and Nadezhda’s, or even “your symphony,” meaning Nadezhda’s.

On December 21, 1877, he wrote:

Dear, sweet, Nadezhda Philaretovna, perhaps I am mistaken, but I think this symphony is something out of the ordinary, the best thing I have done up to now. I am very happy that it is yours, and that hearing it, you will know how at every measure I thought of you. If it were not for you, would it ever have been finished? [During my marriage], when I thought all was ended for me, I wrote on the first draft … ‘In case of my death, I desire this paper to be given to Nadezhda Philaretovna von Meck.’ … Now, thanks to you, I am not only alive and safe, but can give myself fully to the work” (Bowen, 169).

By February 1878, the symphony was complete, and he was very pleased with it, but one thing troubled him, and that was the dedication. He wanted to dedicate it to Nadezhda, but with her well-known desire for privacy, perhaps she would not like that?

In response to this question, Nadezhda asked for a define the relationship. She wrote

“Do you, Pyotr Ilyich, consider me your friend? … As you have never called me by that name, I do not know whether you recognize or consider me so. If you can say yes to that question, I should be most pleased if you would dedicate the symphony to your ‘Friend’ without mentioning the name. If you cannot do so, forget, Pyotr Ilyich, what I have said, and be sure my feeling for you will not change one iota” (Bowen, 98).

Tchaikovsky did her one better. He wrote the dedication: To my best friend.

A Beautiful Friendship

So the years passed, the friendship flourished, and so did the music. In the thirteen years of this relationship, there were only a few times when they ran the danger of actually meeting.

Nadezhda owned several homes and estates, and Tchaikovsky often stayed at them, but generally only when she was somewhere else. On rare occasions, they stayed in separate houses, but very nearby, and twice they made the mistake of actually passing on the road (Bowen, 331). It was super embarrassing. Sometimes they attended the same concerts and spied each other across a crowded audience (Bowen, 295).

Holding the purse strings did not mean Nadezhda always got her own way. Tchaikovsky politely but definitively told her no several times.

When she wanted him to write some piano trios, which contrary to how it sounds means music for a piano, violin, and cello. Tchaikovsky said he disliked that combination of instruments, so no thanks. Or like when she wanted him to self-advertise a little and promote himself, but that would mean—you know—talking to people, so no thanks to that either (Bowen, 309). Or like when she wanted to pay the most influential impresario in Paris to put Tchaikovsky’s music in a concert. Tchaikovsky gently explained to Nadezhda that it would be a great honor if the impresario chose to promote his music in France because he genuinely admired it. To do it because he was paid to do so was entirely different and not an honor at all. Nadezhda backed off (Bowen, 363).

They also disagreed on matters of opinion. She had no love for religion (Bowen, 148); he found great beauty and comfort in the Orthodox church (Bowen, 161). He loved Mozart; she couldn’t see the value of such rigid classicism (Bowen, 232).

None of these disagreements dimmed the friendship or the music. His career was taking off, especially after he began to conduct his own works, which audiences loved. His major hits of this period include the opera Eugene Onegin, the ballet Sleeping Beauty, and the 1812 Overture.

The Friendship Breaks

But the years were passing on. In 1889, Nadezhda complained of bad health and bad headaches that prevented her from writing. By October, she could only dictate letters because her arm was no longer usable (Wiley, 342). She worried about finances, but Tchaikovsky was not distressed by this. She had worried many times before, always unnecessarily. She always assured him that his regular stipend was safe and always would be.

Her last surviving letter was written on September 13, 1890, to tell him of her financial ruin. But we know she sent one more letter after that. In it she cancelled his subsidy and begged him to remember her. We don’t have the letter, but infer the contents because we have his response from October 4, 1890:

“Sweet, dear friend of mine:

Your letter just came; what you have to say grieves me deeply—not for myself, but for you… Certainly it would be false to pretend that such a radical change in my budget will not affect my material welfare, but it will affect it far less than you probably think. In the last few years my income has markedly increased… So if among your many troubles you are troubled also a little about me, I pray you be assured that I have not felt even the smallest passing grief at the idea of this material loss… but [I grieve that you] will have to endure privation …

The last words of your letter (do not forget, and think of me sometimes) offended me a little, but I tell myself you could not really have meant them. Is it possible you think me capable of remembering you only when I use your money? Could I forget for one second all you have done for me, all that I owe you? Without exaggeration I can say that you saved me, and that I would surely have gone mad and perished had you not come forward with your friendship and sympathy… No, my dear friend, be assured I shall remember you and bless you to my last breath… Probably you yourself do not realize the extent of what you have done for me” (Bowen, 428-430).

As regards his finances, this was a polite little fiction. Tchaikovsky certainly had other sources of income, but he spent money even faster, so it made no difference to his bottom line. The rest of the letter was entirely true and heartfelt, and he waited confidently for Nadezhda’s next letter with or without money attached.

The next letter never came. Nadezhda never wrote him again.

Her silence hurt. And what is more, he soon learned from other correspondents that the von Meck fortune was still very largely intact. Tchaikovsky even wrote to other members of her family. Not one of them even so much as said that Nadezhda sends her best wishes or asked how was Tchaikovsky getting on lately?

Tchaikovsky’s friends tried to tell him that their relationship had never been more than a wealthy woman amusing herself. She had gotten tired of the game. That was all there was to it. But Tchaikovsky did not believe it. He wrote to another friend that:

“I wished, I needed my relations with Nadezhda not to change whatever after ceasing to receive money from her …. This situation demeans me in my own eyes, makes it unbearable to recall receiving her financial transfers… I reread [her] earlier letters. Neither illness, nor grief, nor material difficulties, it seemed, could change the feelings expressed in these letters… I could not imagine inconstancy in such a demigoddess; it seemed the earthly sphere might sooner break up into little pieces than Nadezhda change in her relationship to me. But that has happened, and it has turned upside down my view of people, my belief in the best of them” (Wiley, 360).

Since Nadezhda’s words are officially closed, we will never know for sure what she was thinking. Various sources blame various members of her family, who probably didn’t like their inheritance being frittered away on an outsider. Some sources also claim they were embarrassed by this strange relationship and its sexual overtones (Wiley, 348-349). Personally, I think that’s modern readers reading too much in. For one thing, how would they have known what was in all the letters? Even if they did, this was a time period of flowery, sentimental language: to say I love you or I long to hear from you, or I kiss your hands was a sign of affection, but not necessarily sexual. It was common language between family members and close friends.

My own view is as much conjecture as anyone else’s, but contrary to what Tchaikovsky said, I think illness could explain it. She may not have been in full control of her finances anymore. Maybe not even in full possession of her thoughts. We know she could not physically write herself. Maybe she could no longer dictate either. Maybe she couldn’t even read Tchaikovsky’s last letter to her. Maybe her family intercepted it. Maybe she thought the silence was his. Or that he dropped her when the money ended. Maybe she was every bit as hurt as he was.

Like I said, I cannot prove this, but it makes more sense to me than many of the other theories.

The End

Tchaikovsky’s days turned out to be more numbered than Nadezhda’s. He had time to write The Nutcracker and the Sixth Symphony which he thought was a masterpiece, and he was right.

Four years after the last letter to Nadezhda, Tchaikovsky drank unboiled water and died of cholera. In his delirium, he repeated Nadezhda’s name many times. That’s the official story anyway. Rumors of other explanations for his death popped up immediately, but they are all lacking in evidence and this is not an episode on him, so I’m skipping all that.

Nadezhda survived her friend by only two months. When her daughter-in-law was asked how Nadezhda had endured the news of Tchaikovsky’s death, the daughter-in-law said quite clearly “She did not endure it” (Suchet, 244).

One of the benefits of modern life is that you too can support your favorite creator without ever meeting me. If you’d like to be like Nadezhda, the very best way is to sign up as a supporter on Patreon, where depending on the level you choose, you can get ad-free episodes, bonus episodes, double the voting power, and my undying gratitude. If you like your history podcasts, you can get all of those benefits, plus the same for other history podcasts on the Into History network. If you prefer a one-time deal, Patreon also has the bonus episodes available for individual purchase. Or you can also make a one-time donation or buy something from the store. Whatever you choose, I really appreciate your support.

Selected Sources

Bowen, Catherine Drinker, and Barbara von Meck. “Beloved Friend.” University of Michigan Press, 1937.

Brown, David. Tchaikovsky. Faber & Faber, 22 Dec. 2010.

Suchet, John. Tchaikovsky : The Man Revealed. London, Elliott And Thompson Limited, 2018.

Tchaikovsky, Modeste. The Life and Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. London ; New York : J. Lane, 1906.

Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilich. The Diaries of Tchaikovsky. Greenwood, 1973.

Wiley, Roland John. Tchaikovsky. Oxford University Press, 30 July 2009.

I read the transcript today instead of listening to your lovely voice. My text online and in emails often sounds like this flowery correspondence, but it’s only because I’m a big L.M. Montgomery fan. Yes, sometimes it may come across as creepy, but I’m 40 years old with a marriage to work on every day, and I don’t care anymore.

LikeLiked by 1 person