Gandhi is among the most documented figures of the 20th century. His own writings fill over 90 volumes. The number of books about him is too high to count.

Most of these sources reveal astonishingly little about his wife Kasturba. Older sources call her a dutiful, submissive, obedient, and quiet woman. That’s what a Hindu wife of the time period was supposed to be. More recent writers call her feisty, stubborn, and strong. The limited sources haven’t changed. Only our opinions on what a woman should be.

Kasturba left us no writing at all. The biography I used is written by her grandson. It’s a loving tribute, but he was ten when she died. He can’t possibly know some of the motives he ascribes to her. My other sources were even worse about assuming motives. That’s my full disclosure of how sketchy the sources. Even so, this is my best attempt at her story:

A Girl in India

The girl Kastur was born in April 1869. She became Kasturbai when she married and Kasturba after she became a mother (Gandhi, Arun, 1). Her father was a successful trader in Porbandar, a port city on the northwestern side of India. A decade earlier the great Lakshmi Bai (episode 12.12) had been part of rebellions against the British, but those were crushed. The Suez Canal was open. The British were in charge.

At age seven, Kastur was betrothed to a boy named Mohandas Gandhi. (Mahatma is a title; his name was Mohandas.) At age thirteen, they were married, which by the standards of her culture was very, very late.

Child marriage was entirely normal. If a bride was too young to have attracted male attention (or to become hormonal herself), no one needed to doubt her virginity. I could make a lot of caustic comments here, but you’re probably thinking the same, so I’ll skip it.

Mohandas was only thirteen himself. He was attending high school. Kasturbai stayed home and tended the house with the other Gandhi women. No one thought of school for her. There were no schools for girls.

In Mohandas’s own words, “I took no time in assuming the authority of a husband” (Gandhi, Mahatma, volume 1, 33). He told Kastur she couldn’t leave the house without his consent. The next day she went to the temple with his mother. He got angry. She asked if he was seriously suggesting that she disobey his mother. He backed down (Gandhi, Arun, 18).

A little later, Mohandas decided he would teach her to read and write. In general, I approve of literacy but imagine how that went. He was a teenage boy with no teaching experience. He did not ask her whether she wanted to learn; he informed her that she would. She worried that it would set her apart from the other women at a time when she was trying to fit in. In the words of her grandson, “She never protested or openly opposed her husband’s wishes. She simply chose not to master her lessons. A pattern was being set” (Gandhi, Arun, 21). Mohandas gave up.

Separate Lives

In 1885, Mohandas’s father died. Mohandas had older brothers, but you could no longer advance in a career without a British education. His brothers were now too old to get one, so the entire family focused on keeping Mohandas in school. He went off to college, but that didn’t go so well. Eventually someone suggested he should go to England and study law.

This plan was stunningly expensive, so Kasturba’s jewelry was mortgaged. This was not her idea, nor was she happy. Mohandas himself would later write about his departure saying, “She, of course, had begun sobbing long before I went to her and stood like a dumb statue for a moment. I kissed her, and she said, ‘Don’t go.’ What followed I need not describe” (Gandhi, Arun, 34).

Besides the obvious reasons for not wanting him to go, Kasturba had a religious reason. England was not a Hindu nation. Mohandas had sworn to his mother that he would not touch wine, women, or meat, but not everyone believed him. The council of elders excommunicated the entire family, Kasturba included.

In the three years he was gone, Mohandas wrote his wife no letters because she couldn’t read. She raised their infant son without him. What news she got, she got through his brothers. When he returned at age 22, he could speak Latin and French. He had a college degree and a law degree. He could do bookkeeping, play bridge, dance the waltz, play the violin, and speak in public. He wore a Western suit, and he could even tie his own cravat (Gandhi, Arun, 40).

All good things, but he came home to no job, a family in debt, a mother who had died, and a funeral that couldn’t be completed properly because the family was excommunicated. His first order of business was to complete the necessary sacrifices to get his family reinstated (Gandhi, Arun, 46-48). He agreed to the sacrifices, which meant the funeral could be held. But he refused to pay the required fine, which meant he couldn’t visit his in-laws’ home. He never set foot there again. No word on what Kasturba thought of that (Wolpert, 28).

After a fair bit of floundering, the birth of a second boy, and some interactions with Kasturba which proved an expensive education had taught him nothing about tact, Mohandas finally got a job offer he was interested in. It was in South Africa. Kasturba stayed behind while he went out in the world and discovered racism.

A Life in South Africa

Of course, he knew about racism already, but not to the extent that he experienced it in South Africa. He won the lawsuit he had been hired to argue, but he was appalled by the government’s plans for his fellow Indians, so he cancelled his return voyage and stayed to organize politically.

Two years later, he reluctantly agreed that his wife and children should join him in South Africa. This was apparently Kasturba’s choice, not his. One source claims he preferred to devote himself to public work without the distractions of a family, and that’s certainly possible (Wolpert, 52). But I think it’s equally likely that he knew what was waiting for her in South Africa. She was still ignorant.

Mohandas came to India to get her, and he saw that Kasturba had cultural habits that weren’t going to go over well. She ate with her fingers instead of a fork. Her clothes were all wrong too. Mohandas wanted his wife to be respectable in South Africa, and he told her everything she needed to change. She particularly objected to the idea of shoes, but she did it. Years later, she said, “What a heavy price one has to pay to be regarded as civilized” (Gandhi, Arun, 70).

On December 19, 1896, their ship docked at Durban. But no one was allowed to disembark because of a quarantine. The days dragged on, and it became clear that a quarantine was an excuse. Mohandas was the real reason. He had published some unpopular opinions. It was unsafe for him to disembark.

Eventually, a carriage to take Kasturba and the boys to the home of friends. Mohandas would follow on foot. She was probably appalled. In her culture, it would be shameful for a woman to parade through town where strangers could see her. But she did it.

Mohandas was attacked on his walk. He was saved by the wife of the police superintendent. She happened to be passing by, and she waded into the fray, brandishing her parasol. The attackers didn’t want to hurt her, and they fled (Gandhi, Arun, 78).

Mohandas made it to the house, and Kasturba was there, but so was a lynch mob. They spent the night yelling for Mohandas to come out, and that was Kasturba’s first night in South Africa.

Eventually, things calmed down, at least enough for Mohandas to establish the first home Kasturba had ever been mistress of. That was probably sweet, but the culture shock was intense. In South Africa men and women ate and talked together. Women didn’t cover their heads. The European house had no family deity for morning prayers, and no courtyard for evening prayers. The food was inedible. The furniture was uncomfortable. The kitchen forced you to cook standing up. Mohandas still insisted on shoes (Gandhi, Arun, 81-83).

Also, she was more or less alone. Before, she had shared the household tasks with the other women of the family. Certain unpleasant tasks fell to Untouchables, the lowest level in the Indian caste system. The rules for how to interact with an Untouchable were everywhere reinforced in India, but Mohandas had other ideas. He and his family would behave differently. So he informed Kasturba. To his credit, he did take part in these tasks himself. He was not forcing her to do things he would not do himself, but neither was he allowing her to opt out. He wrote much later:

“My wife managed the [chamber] pots of the other [guests], but to clean those used by one who had been [Untouchable] seemed to her to be the limit, and we fell out. She could not bear the pots being cleaned by me, neither did she like doing it herself… I regarded myself as her teacher, and so harassed her out of my blind love for her.

“I was far from being satisfied by her merely carrying the pot. I would have her do it cheerfully. So I said, raising my voice: ‘I will not stand this nonsense in my house.’

“The words pierced her like an arrow.

“She shouted back: ‘Keep your house to yourself and let me go.’ I forgot myself, and the spring of compassion dried up in me. I caught her by the hand, dragged the helpless woman to the gate … and proceeded to open it with the intention of pushing her out. The tears were running down her cheeks in torrents, and she cried: ‘Have you no sense of shame? Must you so far forget yourself? Where am I to go? I have no parents or relatives here to harbor me. Being your wife, you think I must put up with your cuffs and kicks? ‘…

“I put on a brave face, but was really ashamed, and shut the gate. If my wife could not leave me, neither could I leave her. We have had numerous bickerings, but the end has always been peace between us. The wife, with her matchless powers of endurance, has always been the victor” (Gandhi, Mahatma, volume 2, 57-59).

This is Gandhi himself, writing years later. He may say that the wife was always the victor, I can’t help noticing that his household policies did not change.

He had other radical ideas too. When the next two babies were born, he delivered them himself (Gandhi, Arun, 86, 92). No word on what Kasturba thought. Now that he was making lots of money, he decided to cut household expenses (including all paid help) so he could give more money to public service (Gandhi, Arun, 89). No word on what Kasturba thought. He decided that sex was a distraction, and they would take a vow of celibacy. He says, “She had no objection” (Gandhi, Mahatma, volume 1, 483). Modern writers have ascribed all kinds of feelings to her on that last subject: including outrage, relief (Wolpert, 58), and indifference (Guha, 201). Which feeling they choose says more about them than it does about her because as usual, we have no word from her.

We do know she objected when Mohandas gave away a gold necklace given to her as a farewell gift when they left South Africa. He thought it was immoral to accept payment for public service. She thought it was immoral to refuse a gift offered by friends. Mohandas gave it away anyway (Gandhi, Arun, 95-96).

Kasturba was happy to return to her homeland. But it didn’t last. Within only a few years, they were back in South Africa.

Joining a Movement

Until this point, Mohandas’s public work was a thing quite separate from Kasturba, who was neither involved nor consulted. But when the plague broke out in Johannesburg, he suddenly realized she could help. He sent her around to talk to women about hygiene and recognizing symptoms. It was the first time that Mohandas considered her as a companion in public service instead of a distraction from it (Gandhi, Arun, 116). Whether she wanted to be a companion, we again have no word.

However, public service was getting more dangerous. Mohandas was arrested for protesting. Kasturba received 48 telegrams in the following day, all of them congratulating her, rather than commiserating (Guha, 266). No word on what she thought about that.

Mohandas had now fully embraced the idea of satyagraha, which mean “truth persistence.” In practical terms, it meant non-violent civil disobedience. Amazingly, Gandhi credited Kasturba for this idea. He wrote:

“I learned the lesson on non-violence from my wife, when I tried to bend her to my will. Her determined resistance to my will on the one hand, and her quiet submission to the suffering my stupidity involved on the other, ultimately made me ashamed of myself and cured me of my stupidity in thinking that I was born to rule over her, and in the end she became my teacher in non-violence” (Gandhi, Arun, 212).

The authorities were not amused by satyagraha tactics. But then again Kasturba was not amused, when the Supreme Court ruled that marriages were only legal if they had been solemnized with Christian rituals. Kasturba was appalled to be reduced to a concubine. She asked Mohandas what they could do about it.

His answer was quite clear. Women could protest and go to jail, just as the men were already doing. Kasturba considered this. How would she eat in jail? She was sure the prison guards wouldn’t give her vegetarian meals just for the asking. “Perhaps not,” Mohandas agreed. “You might have to fast unto death to make them understand your needs.” He assured her that she need not worry about that too much, for “if you die in jail, I shall worship you like a goddess!” (Gandhi, Arun, 177-178). Then they both laughed.

Or at least, so says her grandson in his biography of her. I can’t speak for how funny Kasturba really found it. I also can’t help noticing that another source reports it all very differently, and says it was Kasturba was the one who suggested she join the protest and go to jail, and nothing was funny (Guha, 447-448).

On September 23, 1913, Kasturba and a group of other women were arrested as satyagrahis. She spent her time in prison leading the women in prayers and hymns and trying to convince the wards they couldn’t eat the food (Gandhi, Arun, 178).

Mohandas and some of her children were in prison too, but he was there to greet her, when she was released after three months. Their protest was effective, and with some concessions granted by the government, Mohandas felt free to leave. The Gandhis arrived back home in India in January 1915. Huge crowds greeted them as heroes.

A Life in India

Later that year, they founded an ashram, or religious retreat. They welcomed families to stay, but the rules were very strict. You lived simply, you helped with all chores, you accepted Untouchables. Kasturba found it even harder to do this last part at home in India than she had in South Africa. But she got over it. It takes time to unlearn the things you learned as a child (Gandhi, Arun, 195-198).

The plain fact of the matter is that it cannot have been very comfortable to be Gandhi’s wife. He demanded a lot of himself, and he expected no less from his family. When faced with a choice between serving humanity and serving his family, he always chose humanity. It was very hard on them. According to one biographer, Kasturba went through five stages with respect to Gandhi’s radical ideas: bewilderment, opposition, acceptance, conversion, and finally championship (Gandhi, Arun, 229).

We have arrived at the championship stage. Mahatma was never happy without a cause to sacrifice himself for, and he found plenty wrong in his home country of India. When he said that cheap foreign cloth was allowing foreigners to dominate the Indians, Kasturba fully agreed to burn her favorite sari. From that point on she spun her own thread (as did he), and she often did it in full view while he conducted important meetings (Gandhi, Arun, 229).

When he was sentenced to six years in jail, she published an open letter. (Which she dictated because she couldn’t write.) In part, it read, “I have no doubt that if India wakes up …, we shall succeed not only in releasing [my husband], but also in solving the issues for which we have been fighting and suffering… If we fail, the fault will be ours” (Gandhi, Arun, 232).

Gandhi didn’t serve six years because he got sick, and the British were afraid of an uprising if he died while in their custody. They released him, he recovered, and carried on with his work.

The British taxed salt and made it illegal to collect your own. So Mahatma planned a salt march, by which he meant a large and very well-publicized walk for hundreds of miles to the ocean where they would collect sea water for the express purpose of illegally extracting the salt. Kasturba stayed behind to take care of the ashram (Gandhi, Arun, 246). He and many of his fellow walkers were arrested, which meant that only the women were left to carry on the movement. He said as much himself in a letter from prison, “I have put all my hopes in you women” (Gandhi, Arun, 249).

Kasturba accepted the challenge. She led the women in a mass picket of the government-owned liquor stores. She knew full well that police were reluctant to arrest women, and those who wanted to cross the strike lines were reluctant to push through a crowd of women. Liquor sales fell dramatically, and Gandhi was delighted (Gandhi, Arun, 249).

The government agreed to talks, but they always broke down. Gandhi was repeatedly arrested, and so was Kasturba. In 1931 and 1932, she was arrested six times (Gandhi, Arun, 253).

When she got out of prison, she had no home to go to. Gandhi had closed the ashram and given the land to Untouchables. She traveled for three years before a new ashram was begun, one that even Mahatma hadn’t planned. He actually wanted a quiet retreat. His adoring fans moved in anyway (Gandhi, Arun, 264).

Kasturba may have been his champion now, but she was still capable of defying him. She fed guests even when he had expressly warned them that this was a place of poverty and not to expect food (Gandhi, Arun, 267). There was also another tiff over the matter of her illiteracy. In 1937 Kasturba was in her late sixties and she herself decided it was time to learn to read. She didn’t ask her husband to teach her. She attended classes taught by someone else. Gandhi still managed to mess it up though. He made some cutting remarks about her handwriting. Her response was to say, “I am done with my lessons for life, thank you,” and none of his apologies could persuade her otherwise (Gandhi, Arun, 265, 290).

In 1939, Gandhi was in prison, fasting to the death. The Brits were super nervous, yet again, that he would die in their custody. At the time, they had Kasturba in another prison, and the authorities whisked her to him in the hopes that he’d eat for her. He opened his eyes and asked her how she could have allowed herself to be released when her companions were still in jail? She went back to the other prison and asked to be reincarcerated. The despairing officials gave her shelter for one night and then released the whole group.

Ending a Life of Service

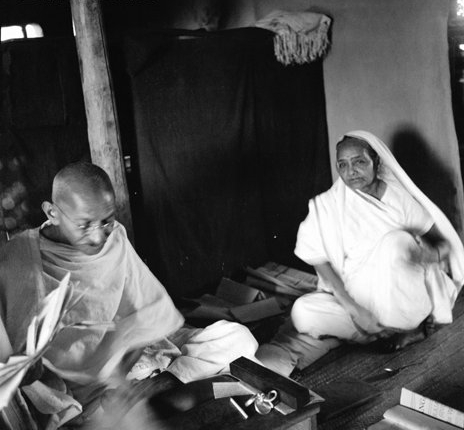

In 1944, both Gandhis were in jail (again). Only this time, Kasturba was 75 years old and very ill. She died on February 22nd and her grandson says that even the prison guards cried (Gandhi, Arun, 300).

At her funeral, Gandhi read passages from the Bhagavad Gita, but also the Qur’an, and the New Testament. He said, “Without my wishing it, she chose to lose herself in me, and the result was that she became truly my better half” (Gandhi, Arun, 303).

Kasturba didn’t live to see it, but three years later, the British transferred power to the Indian people. Gandhi was invited to participate in celebrations, but he found nothing worthy of celebration. He had devoted his life to fighting oppression and intolerance. The British were not taking oppression and intolerance away with them. Hindus and Muslims were destroying each other in their wake. Gandhi did not consider that a victory. To this day, India is largely Hindu and Pakistan is largely Muslim. The border is militarized. That is not at all what Gandhi wanted. Only a few months after the partition, he was assassinated by a Hindu fundamentalist.

Gandhi may have considered his work a failure, but he inspired countless others, and my point today is that he didn’t do it alone. Kasturba did it too.

Selected Sources

Gandhi, Arun. Kasturba: A Life. Penguin UK, 2000.

Gandhi, M.K. My Non-Violence. Edited by Sailesh Kumar Bandopadhyaya. Navajivan Publishing House, 2021. https://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/my-nonviolence/index.php.

Gandhi, Mahatma. The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Navajivan Trust, 1927. https://archive.org/details/gandhisautobiogr02gand/page/56/mode/2up?q=matchless.

Guha, Ramachandra. Gandhi before India. Vintage, 2014.

Roell, Sophie. “The Best Books on Gandhi.” Five Books, May 26, 2021. https://fivebooks.com/best-books/gandhi-ramachandra-guha/.

Wolpert, Stanley. Gandhi’s Passion. Oxford University Press, 2002.

[…] found this idea very attractive (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 160-161). I covered Gandhi’s wife Kasturba a couple months ago (episode 14.15) and there’s no doubt that Kasturba found Gandhi’s ideas very, very hard at first. But Kasturba […]

LikeLike

[…] English versions. But what is nice is that he didn’t see this as something to impose on women. His wife Kasturba (episode 14.15) did spin cotton on a traditional Indian spinning wheel, but Mahatma Gandhi spun […]

LikeLike