There is more than one way to stand behind a famous man, just like there’s more than one way to be famous. This one will be different than our previous nineteen in this series.

Mao Zedong was a leader who rose to prominence in the 1930s when the Chinese Communist Party was fighting for its life against the Nationalist Party and the Nationalists were winning. The fact that they didn’t win outright was due in large part to Mao’s leadership as the Communists retreated 6,000 miles to northern China while losing about 90% of their soldiers along the way. If you survived the Long March, you were a hero. If you were its leader, you were as revered as any emperor ever was. That’s a bit ironic for a movement that despised emperors and celebrated the ordinary-as-dirt masses, but let’s be honest, capitalist democracies also have their own ironies.

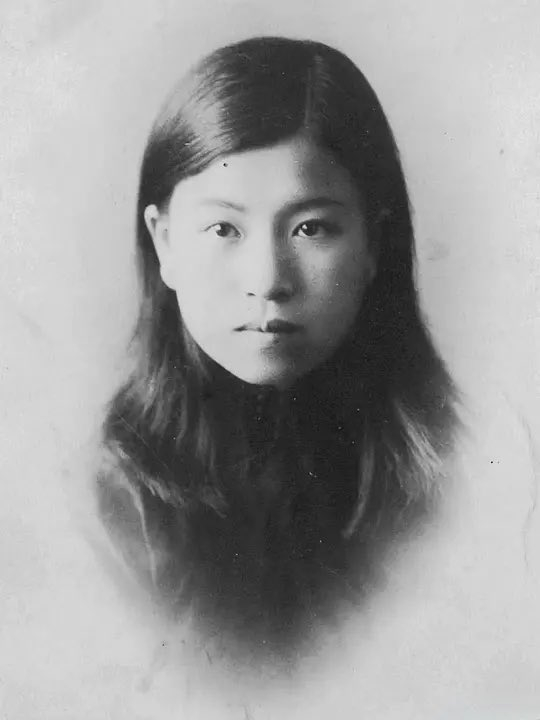

A Difficult Girlhood

Politics of any kind was irrelevant to a little girl in Shandong province. Her father was an alcoholic and whose mother was a low status concubine. It’s often the case that we don’t know much about the early years of the women I cover on this show, but in this case, I’m pretty dissatisfied with my sources for Jiang Qing’s entire life. There are a gazillion books written about Mao, but almost none written about his wife, despite the fact that she was arguably the most influential woman in China in the 20th century. Besides the usual underreporting on women in history, there’s also the fact that sources on Jiang Qing were hidden, destroyed, or doctored. The one biography I’ve got to work with is decades old and had some sourcing (and possibly inventing) problems even when it was written. It’s written by an Australian-American living during the Cold War, which undoubtedly colors the presentation, but it seems that Chinese sources aren’t always eager to write about Jiang Qing either. In fact, the most recent and popular treatment of her life is a novel, but in multiple places I saw it touted as a reputable source for history. For the record, I love novels, but I don’t use them as sources on this podcast. What I’m saying is that if you need a PhD in Chinese history, please publish and new view of Jiang Qing, I will be delighted to do an update to this episode. In the meantime, I’m working with what I’ve got.

Jiang Qing’s mother eventually fled from abuse and returned to her own family, which seems a pretty obvious step for an abused woman to me but was no guarantee in traditional China. Yunhe (which was Jiang Qing’s name at the time) was now in the care of her grandfather, but she had scant respect for the Confucian Three Obediences that were supposed to dominate the female life. The Three Obediences are ① a girl must obey her father, grandfather in this case, ② a wife must obey her husband, and ③ a widow must obey her son (Terrill, 28).

Yunhe said forget that. She ran away with an acting troop, where she quickly realized she had exchanged obedience to her grandfather for obedience to her boss (Terrill, 30). It wasn’t an improvement. Grandpa had to pay to get her released, but she was then accepted into an arts academy where she learned both traditional and Western drama and music. Sadly, she could not graduate because the school closed for budget cuts (Terrill, 34).

At age 16, she was at loose ends, but she’d caught the eye of a local farmer. He proposed and since getting married was what a Chinese girl was supposed to do, they got married. Trouble was, she didn’t really like doing what Chinese girls were supposed to do. They got divorced only a few months later (Terrill, 40).

On the Stage, On Her Own

Yunhe moved to Qingdao, got herself a job at the University library and audited some classes. She also got a common-law husband who was more to her liking. He was a fellow student and a leader in the Communist underground. He signed her up as a Communist too, though it’s not clear that she even knew what that meant (Terrill, 40-44). Then he got arrested and jailed.

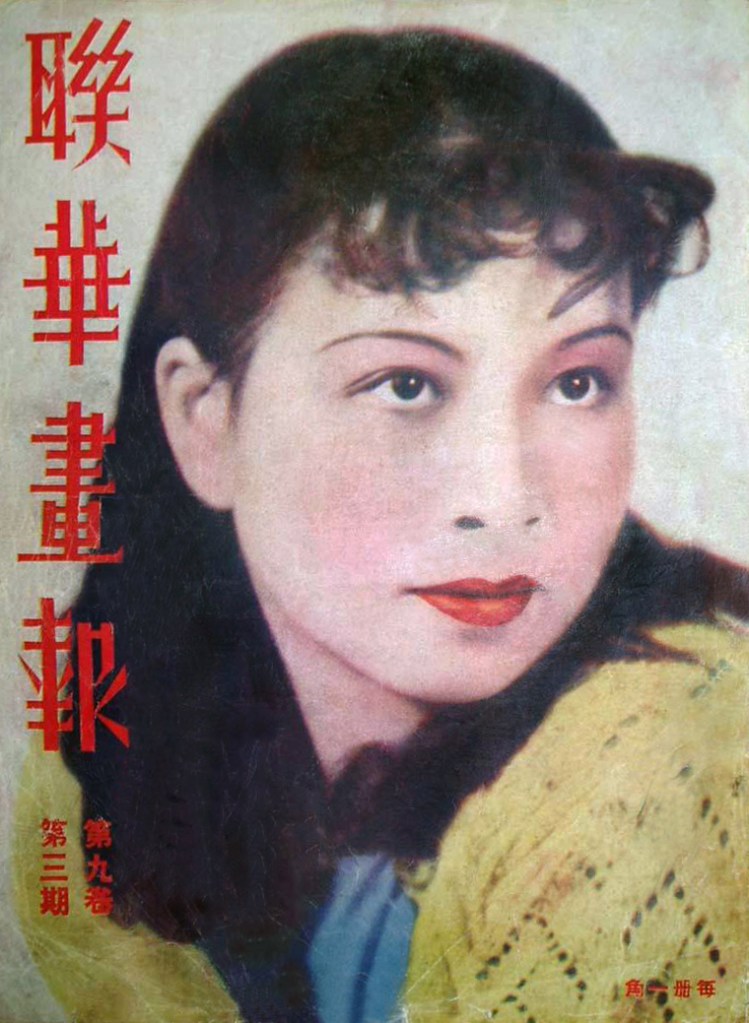

Yunhe cut her losses. She moved to Shanghai and changed her name to Lan Ping. She supported herself with minor roles in theater and a teaching job at a night school for women workers. Also, she handed out leaflets for the Communists, which got her arrested and jailed. After three months in prison, she signed a confession and declared herself a Nationalist and walked free. It’s still not clear that these party labels were anything but words to her (Terrill, 52-60).

So while the Communist army was dying in large numbers on the Long March, Lan Ping was living it up in the theater district of Shanghai. She took larger and larger roles on the stage. She enjoyed makeup, clothes, fans, Western movies, and a string of low commitment relationships.

She also got married for the third time. It was a stormy and well-publicized marriage that included breakups, affairs, and a suicide attempt (his, not hers). Real good tabloid stuff, which is exactly where it was publicized. They broke up for real in 1937, and Lan Ping published an essay on why none of it was her fault.

1937 was also the summer the Japanese attacked Shanghai. In episode 8.9, I told the story of Zheng Pingru, another young actress in this same city at the same time. Zheng Pingru stayed in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, became a spy, and died for it. Lan Ping took the other route. She fled the city. It was a much safer option (Terrill, 110).

Becoming a Communist

She ended up in a place as different to Shanghai’s theater district as it was possible to get. Up north, in the Communist encampment at Yanan, the great Mao Zedong lived in a cave and directed the operations of the party members, who wore unisex gray clothes, slept on hard wooden beds, and mostly did without toilets, cars, or industry of any kind (Terrill, 126-131).

Neither the Communists nor Chinese culture were big on individual self-will or self-expression, but Lan Ping managed to make her presence known just the same. She was enrolled in the Party School, and when Mao came to give a speech she drew attention to herself by clapping longer than anyone else (Terrill, 134).

Since she didn’t know much about Communism, she had a lot of questions, and she wrote Mao a letter, asking for a face-to-face meeting so he could explain it to her. Without waiting for an answer, she showed up at his cave and basically invited herself in. If she hadn’t been young and pretty, this might not have worked. But she was young and pretty, and it did work (Terrill, 134).

By August 1938, Lan Ping’s work assignment was in the archives, conveniently near Mao’s office (Terrill, 138). She was 23. He was 40. They were happy. But no one else was happy.

Chief among the unhappy people was Mao’s wife, He Zizhen. She was a veteran of the Long March, a heroine of the Revolution, a mother of six of Mao’s children (he had more). She made her displeasure about this young tramp very, very clear.

Her motives were obvious, but she wasn’t the only one who disapproved. By Party standards, Lan Ping was hopelessly unsuitable. Had she survived the long March? No. Had she once signed a confession and declared herself a member of the Nationalist Party, otherwise known as our mortal enemies? Yes. Some people suggested that tramp didn’t even begin to cover the depth of her depravity. What if she was a secret agent? (Terrill, 149).

Mao overrode any objections. He said he wanted Lan Ping, that he could not go on without her, and so he would quit the Revolution if he couldn’t have her. So really, his divorce for the good of the Party and China itself. It was semi-traitorous to suggest otherwise. (In some ways, he’d have gotten on well with Henry VIII, who was certainly no Communist.)

He Zizhen was packed off to the Soviet Union for her health (Terrill, 214). The divorce was granted, and Lan Ping got married fourth time. It was Mao’s fourth marriage too.

Madame Mao

To mark the occasion, Lan Ping changed her name for the last time to Jiang Qing, which means Green River (Terrill, 160).

However, that was about all Jiang Qing was able to do. The Party extracted a price for allowing a woman with her sketchy background to dream so high. In theory, women had better opportunities under Communism than under previous systems. The masses were celebrated, and there were certainly masses of women. Communist regimes throughout the world recognized that women were fully capable of working hard to benefit society, and they put them to work, though roll out was hampered by the fact that they forgot women had been working all along. They often failed to make adequate provisions for little things like cooking, sewing, childcare, etc. But in the early days of the Communist revolution in China, women like He Zizhen did hold real party positions with titles and responsibilities and power. Not too much power, but some. Jiang Qing might have thought she was destined for one of those, but she was disappointed. The Party demanded that her job was to look after Mao. Nothing else. She could play no political role whatsoever. She was to be a housewife.

To me, this doesn’t initially sound so bad. I would pay good capitalist money to be a housewife instead of a politician. I’d be terrible at politics. But Jiang Qing didn’t feel that way, and besides, in Communist China pretty much every role was political. Certainly Jiang Qing’s specialty of the performing arts were. Art was a tool to promote the party agenda. Mao said so, “There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake” (Zedong, “Talks at the Yenan Forum”).

So Jiang Qing, the girl who had refused to accept any situation she didn’t like, sort of disappeared into marriage, just like a traditionally Chinese woman was supposed to. She was married in 1938. Her only child was born in 1940, and Jiang Qing was still a political nonentity in 1947 when Nationalist bombing forced them to evacuate Yanan. In 1949, the Communists emerged victorious on the mainland and the Nationalists fled to Taiwan.

First Lady of the People’s Republic of China

As First Lady of the new People’s Republic of China, you might think Jiang Qing would take a visible role in the 1950s, but you’d be wrong. Partly this was because she was ill and frequently in the Soviet Union for treatment. But it’s hard not to notice that that’s exactly what happened to He Zizhen, and certainly Mao had long since discovered that China could provide an endless supply of young pretty girls.

A younger Jiang Qing might have pitched a fit. But He Zizhen was a cautionary tale. I am not entirely certain that it would be fair to say that Jiang Qing’s goal had been to sleep her way to the top. But if it was, she had succeeded. There was no higher to go. As Jiang herself said “Sex is engaging in the first rounds, but what sustains interest in the long run is power” (Terrill, 123). In practical terms, this meant that she said nothing about Mao’s infidelity. She just got ill and depressed. But in the 1960s the political landscape changed.

Mao’s Great Leap Forward was a plan to quickly industrialize Chinese cities and collectivize Chinese farms. The goal was to eliminate private property, so the wealth could be shared by all. The agricultural quotas set for each commune were ridiculous. They were set by visionaries, instead of—you know—actual farmers. These politicians and bureaucrats had never planted a crop, much less harvested one. But that didn’t stop them from issuing detailed instructions that were both mandatory and an ecological disaster. If you voiced any concerns about the plan, you were a rightist, a traitor, a capitalist, and you were hounded out of your job, your community, and possibly your life.

The result was that local officials falsified their reports and claimed to have huge harvests. As proof, they sent their enormous surplus into the cities, leaving virtually nothing for the local commune members to eat. When shortages became obvious, these same local commune members were accused of having hidden the harvest and punished. It was the only possible explanation. It was certainly not because anything was wrong with the plan.

Hard numbers on how many people died are difficult to know, given how all the reports were falsified. But even the middle ground estimate is 30 million. Yes, 30 million. In the words of author Clive James, this means that “Mao killed more of his own people than Hitler and Stalin put together ever managed to kill of theirs. But since Mao held the monopoly of publicity, none of the blood showed. The world saw only the waving flags.” (James, chap 6).

By the mid 1960s, even Mao could no longer pretend that all was well. The Party loyalists were getting restless in the face of overwhelming evidence that the policies were a disaster on an unimaginable scale. Also Mao was in the early stages of Parkinson’s. He needed help. And what is a wife for, if not to be a loyal helpmeet? Jiang Qing’s moment had come. The Revolution needed a shot in the arm.

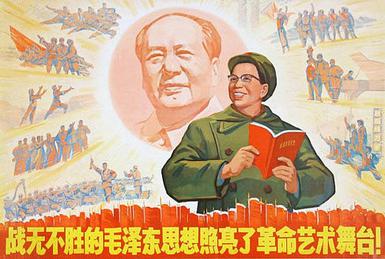

The Cultural Revolution

Jiang Qing began saving the revolution in the field where she felt most knowledgeable: the theater. Her new slogan was “Make it revolutionary or ban it” (Terrill, 263). And she did. Every play must have a sharp moral message, depicting the class struggle. If that means rewriting a piece of classic literature that had delighted audiences for centuries, then rewrite it. She moved on to the other arts. For example, she informed the Philharmonic that “the capitalist symphony is dead” (Terrill, 250). People like Beethoven weren’t Communist enough.

By 1966, Jiang Qing’s had an official position doing this art-as-propaganda gig and it put her in the mainstream of power. She was leading political rallies and giving the act of her life to an audience of millions (Terrill, 256). The Cultural Revolution had begun.

It was soon much bigger than just art. The rationale was explained as purging the Four Olds: old ideas, old customs, old culture, and old habits. This meant throwing out capitalist stuff like jeans, sunglasses, and books in English. But also many things that Chinese had treasured for centuries, like statues of Buddha, ancestor scrolls, paintings of nonrevolutionary subjects like birds or mountains. Authorized gangs of soldiers and unauthorized gangs of teenagers ransacked people’s homes looking for such contraband.

As for the people who created or cherished such objects, they were purged, either by actual death or by reeducation in a labor camp, which was almost the same thing. About 2 million more people died.

Some of those people happened to be those who had wronged Jiang Qing at some point in the past, including her days in Shanghai or Yanan. She included their families too (Terrill, 263). It was easy enough to find an excuse when all you had to do to deserve death was cherish something old.

In the place of all these great things that were no longer part of people’s cultural lives, they were to wear clothes designed by Jiang Qing and watch Peking operas and movies approved by Jiang Qing. Most of all they were to read the little Red Book of teachings by Mao.

Filling the Power Vacuum

Mao himself was mostly behind the scenes because his health was bad. His deputies were on the frontlines making things happen, and the most powerful group of these was the Gang of Four, led by Jiang Qing. What was obvious to everyone in the Gang and also to their powerful rivals was that Mao would not live forever. Someone was going to fill the void when he died.

Increasingly, Jiang Qing wondered if it could be her. The odds were not favorable. As I said earlier, Communist states liked to pretend they gave opportunities to women, but there were still vanishingly few women in the upper echelons of power. If you looked further back to 4000 years of imperial history, China only ever had one reigning empress, Wu Zetian, episode 2.3. Jiang Qing became very interested in Wu Zetian, which I don’t really understand because Wu Zetian was definitely an old idea. But when you control the propaganda wing of the government, that’s easily fixed. Jiang Qing hired writers to produce articles showing that Wu was anti-Confucian and progressive, which is a creative take (Terrill, 311).

Anyway, Jiang Qing’s campaign seemed to be working. By 1974, she was listed first on many gatherings of Chinese leaders (Terrill, 326). There’s a famous photo of her hosting Richard Nixon, when he made his famous trip to mend US-China relations.

By 1976, the man with the title of First Premier (basically Mao’s second in command) died. Jiang Qing and Deng Xiaoping battled over his replacement. Hua Guofeng was appointed as a compromise.

And then the Great Mao was on his death bed. In his last meeting with the Party leaders he could barely speak. Reports of what he said vary wildly. He might have mumbled “Help Jiang Qing to carry the Red Flag!” In other words, help her to become Chairman of the party.

Or he might have said “Help Jiang Qing to correct her errors!” Meaning Mao did not approve of everything she had done (Terrill,363).

Or he might have said nothing of the kind. The document that records this is suspected of tampering (Hsu, 15).

Mao also wrote to Hua Guofeng that “With you in charge, I am at ease” (Hsu, 8). Meaning that Hua should be Chairman. And then, without clarifying himself, Mao died.

The stage for a showdown was set. By titles alone, Hua was the obvious successor. He also had Mao’s chief bodyguard and a unit of 20,000 men. But Jiang Qing had control of the media, the urban militias, and a couple of key industrial areas. The army was split.

Both sides were planning a coup, but Hua pulled his off first (Hsu, 18). Armed men broke into Jiang Qing’s home while she slept and arrested her.

The problem with a media that supports you because they were ordered to support you is that they will turn on you just as fast when the orders change. Cartoons appeared all over China with Jiang Qing’s name written in skeletal bones, instead of calligraphy brush strokes. She was a witch, a siren, a rat. People shouted in the streets “Ten Thousand Knives to the Body of Jiang Qing.” They started calling her the White-Boned Demon (Terrill, 373).

Madame Mao on Trial

It took the Party four years to bring her case to trial. Hua Guofeng wasn’t even in charge anymore. His leadership skills weren’t up to the task. But the Communist Party was in a ticklish position. They needed to repudiate the failed policies of the past, but they also needed to justify their continued existence. Chairman Mao was a god, the reason the Party existed. We don’t criticize him even when we walk back many of his policies. There had to be someone else to blame.

At her televised trial, Jiang Qing was accused of two broad sets of crimes: she persecuted people (which was true) and she tried to usurp power (which was also true).

In response, Jiang Qing had two lines of defense: that her judges and accusers were guilty of exactly the same thing (which was true). And also that “Everything I did, Mao told me to do. I was his dog; what he said to bite, I bit” (Terrill, 15, 382-386). In other words, if you want to blame someone, blame Mao. Which she knew perfectly well the Party didn’t want to do. The prosecution did introduce reports of daylight between Mao’s opinions and Jiang Qing’s actions. So it may be that he did not originate all of her actions. But if he had wanted to stop her, he could have. He didn’t.

By now, Jiang Qing and the judge were in a shouting match with each other. This is against the rules in a Western court, but it was even more surprising in a Chinese court. The expected behavior was to start confessing because the Party accused you and the Party is always right (Terrill, 386).

Jiang Qing made no apologies. The chief judge concluded that “She refused to present her case within the framework of the accusations… but instead made use of the debate to make counterrevolutionary remarks.” A Beijing newspaper was more blunt, saying “Jiang Qing’s ugly performance shows that she has not yet awakened from her feudalist dream of staging a comeback. Perhaps she will die unrepentant. Let her do so” (Terrill, 390).

She was found guilty on all counts. The sentence was death, suspended for two years contingent on her good behavior. In fact, she lived for another eleven years. She died in 1991 after being released for medical treatment. It wasn’t her medical condition that killed her. Security was lax, and she succeeded in hanging herself in the bathroom.

Jiang Qing provides us with plenty to criticize. She is not a model I’d hold up for other women with political aspirations. However, it’s still a little hard to swallow that at the end of the day, the most visible way she helped the famous man in her life was to take the blame for him. She deserved some of the blame, yes. But she didn’t deserve all of it.

Selected Sources

Brown, Clayton. “China’s Great Leap Forward.” Association for Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies, 2012. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/.

Carter, James. “The Death of Jiang Qing, A.k.a., Madame Mao.” The China Project, May 19, 2021. https://thechinaproject.com/2021/05/19/the-death-of-jiang-qing-a-k-a-madame-mao/.

Friedman, Edward. “The Persistent Invisibility of Rural Suffering in China.” Indian Journal of Asian Affairs 22, no. 1/2 (2009): 19–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41950494.

Honig, Emily. “Review of The White-Boned Demon. A Biography of Madame Mao Zedong.” Political Science Quarterly 100, no. 2 (1985): 357–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/2150693.

Hsü, Immanuel C Y. China without Mao : The Search for a New Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. https://dokumen.pub/china-without-mao-the-search-for-a-new-order-2nbsped-9780198022657-9780195060560.html#:~:text=The%20%22Deathbed%20Adjuration%22%20During%20the%20mourning%20period%2C,appeared%20more%20preoccupied%20with%20succession%20than%20grief.&text=A%20June%203%2C%201976%2C%20document%20of%20Mao’s,help%20Jiang%20Qing%20carry%20the%20Red%20Banner..

Ip, Hung-Yok. “Fashioning Appearances: Feminine Beauty in Chinese Communist Revolutionary Culture.” Modern China 29, no. 3 (2003): 329–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3181296.

James, Clive. Fame in the 20th Century. Random House (NY), 1993. https://archive.clivejames.com/books/fame6.htm.

Joseph, William. “Review of The White-Boned Demon. A Biography of Madame Mao Zedong.” Pacific Affairs 58, no. 2 (1985): 308–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/2758274.

Lamb, Stefanie. “Introduction to the Cultural Revolution.” Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. Stanford University, December 2005. https://spice.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/introduction_to_the_cultural_revolution.

Marxists.org. “The Jiang Ching (Chiang Ching) Internet Archive,” 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/jiang-qing/.

Terrill, Ross. Madame Mao : The White Boned Demon : A Biography of Madame Mao Zedong. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1984.

Wright, Elizabeth. “Review of The White-Boned Demon. A Biography of Madame Mao Zedong.” The China Quarterly, no. 106 (1986): 367–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/653454.

Zedong, Mao. “Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art (May 2, 1942).” Marxists.org, 2020. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_08.htm.

[…] when educational opportunities were opened to women and then it was deliberately crushed by the Cultural Revolution, but I am pleased to say that Nüshu is experiencing a revival. People are trying to preserve […]

LikeLike