A woman’s first needs are water and food. Swiftly following those, she needs something to wear. Not just because she needs to look good (though there is that), but also because human skin is ridiculous. Our fur, such as it is, fails to keep us warm in many environments, yet our skin burns in other environments. And let’s not even get started about the insects. We don’t even have a tail to help brush them off.

While food and water do exist out in the wild world (free for the foraging, to a limited extent), fabric is human-made from beginning to very frayed end. Your daily ritual of getting dressed in the morning is the culmination of invention after invention after invention over millennium after millennium.

Sigmund Freud gave women the dubious honor of having made many of those inventions. He said, “it seems that women have made few contributions to the discoveries and inventions in the history of civilization. . . There is, however, one technique which they have invented—that of plaiting and weaving.” Women developed these skills, he continued, in response to a subconscious feeling of shame and “genital deficiency” (quoted in St Clair, 14).

<Please boo and hiss here.>

There are so many things wrong with that statement it’s hard to know where to start, but let’s just say that we don’t have the foggiest clue which gender invented any of the pre-historic developments, like the wheel or fire or writing. Women may be responsible for all of them. Or none. Or maybe just a healthy mix. And I don’t know about you, but I think feeling chilly is a much more compelling reason for inventing clothes than genital deficiency. So much for Freud.

Creating the Fibers

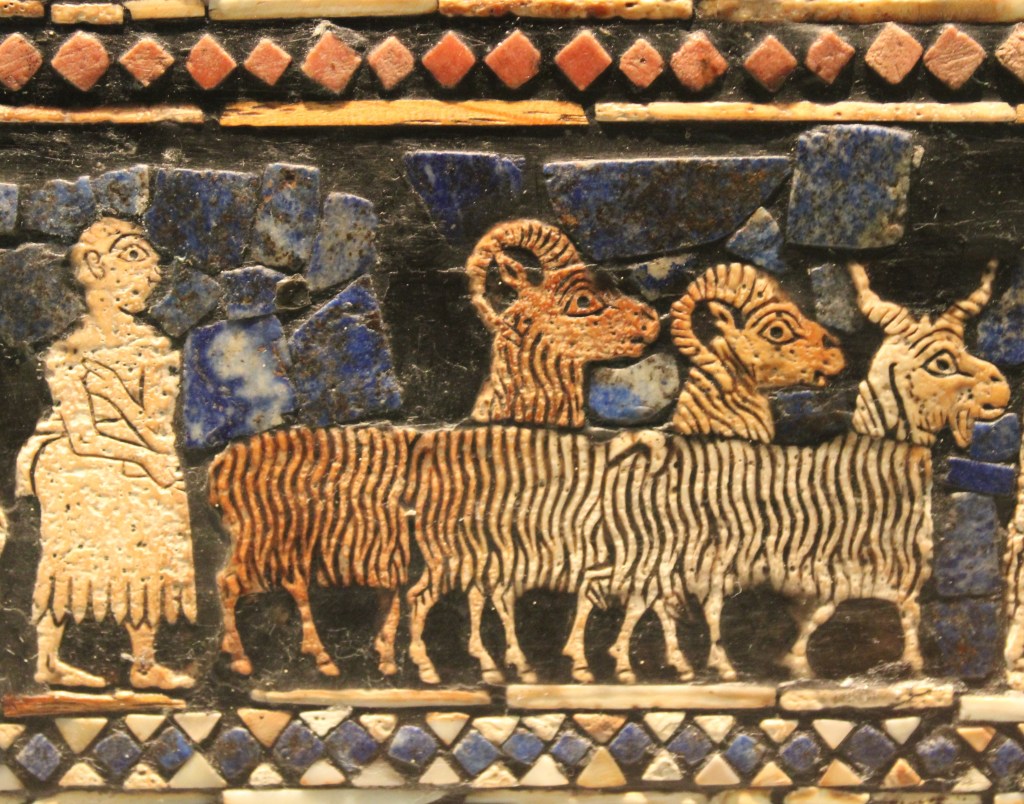

The first invention needed was the fibers themselves. There are lots of possible options in the natural world, but none are very useful in their natural, God-or-evolution created state. The four biggies turned out to be wool, cotton, flax, and silk, but humanity could only know that after intensive selective breeding. Wild sheep, for example, have short scraggly hair that molts irregularly, in patches. It took 2,000 generations of selective breeding to get the fluffy ones visible in Mesopotamian art (Postrel, chap. 1). There are fifty wild cotton species, coming from multiple continents, but those plants are fussy about where they grow, and their cotton balls are small, with very short fibers, and the whole little ball is stuffed with seeds that have to be picked out one by every last one (Postrel). Flax and silk had their own issues. None of this was easy.

Even after breeding for more fibers, longer fibers, and collectible fibers, congratulations, you’ve achieved very thin fibers that can be still measured in inches or centimeters. Most textile workers trash threads that size. They’re not very useful.

Creating the Thread

The answer is called spinning. Spinning is how you take fibers that are too short, too thin, and too fragile and turn them into long, continuous strands of strong thread or yarn.

In a small way, you can try this at home. Take an ordinary cotton ball. (By ordinary, I mean very soft, very clean, very white, very deseeded cotton. In other words, highly processed and not ordinary at all, but let’s ignore that part.) Pull a little bit of the cotton out. It’ll be loose and fluffy, but you can roll it between your fingers or to be more historically accurate, roll it between your palm and your thigh. It will become longer and tighter but leave one end a little fluffy. Pull a little more loose cotton out, overlap it with the fluffy end of your previous yarn and roll that bit, until it gets twisted up with the previous bit, making your yarn a little longer. Repeat ad nauseum.

I gave this a go and completed about a handspan of lumpy, knobbly yarn before I got totally bored. For context, a pair of jeans contains about six miles, or almost 10 km of yarn. A queen-sized sheet takes more than six times more than that (Postrel, chap 2). And my lumpy yarn isn’t good enough for any of that.

To spin good thread requires four hands: one to hold the fiber, one to draw it out, one to twist, and one to hold your new yarn so it doesn’t get tangled up. And people all over the world invented a solution to this, which is called the drop spindle.

The Drop Spindle

A drop spindle is a stick with a weight on one end and a hook on the other. You hold your bundle of fibers in your left hand and place the hook onto a little of the fiber on the bottom. Then your right hand sets the spindle spinning. The spin will do the twisting for you and gravity will pull the stick down. You’ll get nicer, more even thread getting longer and longer between your bundle of fiber and the descending stick. When it gets too long to handle, you can pause and wind your new thread around the stick, leaving just the bit at the top through your hook. Start again. Repeat ad nauseum. (If you’re finding this hard to picture, check out this video:

Our oldest evidence of drop spindles is from 12,000 years ago in Israel (Yashuv). The thread made on them has long since rotted away, as have the sticks, but the weights (or whorls, as they are called) don’t rot because they are often rocks, metal, or pottery with a hole through the middle. They are easily identifiable and a dime a dozen at archaeological sites all over the world, in China, India, Africa, Meso-America, Europe. Everywhere, really. Many museums have thousands of spindle whorls. Mostly not on display, because most of them are not all that interesting, though they can be very decorative.

Not all aspects of the textile business were always assigned to women, but so far as we have records, spinning was a woman’s job. Doesn’t matter the time, place, or the culture, women of practically all socio-economic levels were doing it. It was a basic life skill, like cooking or cleaning. We can run through a list of reasons why this is so. Spinning required fine motor skills, but no great strength. It combined well with watching children or the pot boil because you could do it indoors or out, virtually any time of day, with frequent pauses as necessary.

It is difficult to overstate just how time consuming this was. A good spinner can produce about 260 yards of yarn an hour (McCune). A little quick math, and that means it takes 40 hours of skilled work to produce the thread in your favorite pair of jeans. Just the thread, mind you. That doesn’t count the growing, harvesting, deseeding, cleaning, and carding of the cotton which came before. Nor does it count the weaving and the sewing which come later. And that’s just a pair of jeans. Imagine something much bigger. Like a set of sails for a ship. Those fancy Viking ships that terrorized the western world from about 793 to 1066 CE were very impressive. Not so much for the woodcraft, but for the sails. The sails were much more expensive than the ship itself (Postrel, chapter 2).

The Spinning Wheel

Viking women used the drop spindle to make those sails. But at the same time, elsewhere in the world, some women were using a new invention: the spinning wheel. The spinning wheel was invented by an unnamed silk spinner in China, according to one of my sources (Postrel, chapter 2) and by an unnamed cotton spinner in India, according to another of my sources (Finlay, 98). I say, why not both?

I’m not going to explain how the spinning wheel works, partly because a video is worth a thousand words, and partly because there are a lot of variations. They don’t all work the same.

The main benefit of the wheel is that it provides the twist, and you might be keeping it turning with a continuous foot treadle, rather than spinning your drop spindle over and over with your hand. It’s steadier, which means you get more even thread. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Here are the words of author Victoria Finlay:

“When I first sat down at the spinning wheel, I was confident that it couldn’t be harder than using the drop spindle. I expected that I would be flicking the treadle and spinning along in no time. Instead it was like being on a bicycle for the first time. There were so many near-impossible acts of balance and coordination to be managed simultaneously that I simply couldn’t imagine doing them all at the same time. If I paused on the treadle at the wrong point, the wheel would reverse direction, with the weight and plunge of a playground swing, sending all the other elements into free fall. If I paid any attention to that, then my hands would freeze and forget to draw out the thread to feed into the tube leading to the flyer and it would either wind itself into a frizz or—more often—break.” (Finlay, 99)

Bear in mind that Finlay was using a single drive wheel, which is one of the easiest for beginners. There are more complicated versions.

The spinning wheel migrated into Europe during the Middle Ages, but it never fully replaced the drop spindle, partly because it could only handle certain fibers and partly because so many women couldn’t afford a fiddly piece of machinery.

Getting Paid for Your Work

Whatever the method, spinners were always, always in demand because no spinner could keep up with a weaver. I’ve read varying estimates, but it took anywhere from eight to twenty full-time spinners to supply one weaver (Postrel, chapter 2).

Basic economic theory suggests that if the product you make is in demand, you should be well paid, right? Well, think again. Spinning was very badly paid. Many women, of course, were doing it for their own household use, so they weren’t paid a wage at all. Others were doing it as slaves, so ditto. But if you were hiring out, you earned a pittance. For example, in England in 1768, spinners were paid one shilling a week. For context, a weaver got paid nine shillings a week if he was a man or five shillings if she was a woman, but that’s still five times more than the poor spinner (Postrel, chapter 2).

Sexism was definitely in play here, but it’s too easy to say that sexism was the only thing keeping the wages low. It was also a plain fact that the amount of thread a spinner could make in a day was pretty much useless. Hence, the pretty much useless daily salary. It took enormous quantities to become valuable. If spinners had earned a better salary, no one could have afforded the end product.

Low pay was one of several reasons why women dreaded being single. A woman alone probably wasn’t destitute in the sense that she could make no money at all because there was always spinning. But the pay was so low that without other resources, she was pretty close to destitute.

Linguistic and Literary Remnants

On the plus side, spinning was an activity that women brought women together to socialize. Your hands are busy, but your mind and tongue can wag. You can still see evidence of spinning. If you are a telling a far-fetched story, you might call it “spinning a tale” or even “spinning a yarn.” A single woman who has passed the usual age of marriage was in the past called a spinster. Not so much now, but in the past, we referred to our mother’s side of the family as the distaff side. A distaff was a long stick where spinners tied their yet-to-be-spun fiber, so it would hold together as they drew it out.

Then there are the tales about spinning. You can imagine that the mostly powerless women at work with their spindles liked telling the stories of the three Greek fates, who controlled the fates of men by spinning a thread that began at birth and cut off at death. Impoverished spinners probably liked pretending that Rumpelstiltskin might show up to show them how to spin straw (or flax) into gold. And the tale of Sleeping Beauty is perhaps the most desperate: Surely, surely we could just prick our finger on this machine and sleep until a handsome prince shows up to rescue us? Yes, please.

These are folktales, and we don’t know the original authors. But it would make sense for them to be women, wouldn’t it? (Take that, Freud.) Another story that I think was female-authored isn’t so famous. It appeared in the original Grimm’s Fairy Tales, told to them by a woman named Jeanette Hassenpflug, and it’s short, so I’m going to tell it in full, but there are two things you might need to know. One is to remember that a spinning wheel can be controlled by a foot pedal. And the other is that when spinning flax, it’s common to lick your fingers as you go because moist fibers lie flatter and smoother. Okay, here’s the story:

Once upon a time, there was a king who loved linen. The queen and the princesses spun all the time, for he was very angry if he couldn’t hear the spinning wheels. One day he went abroad, but before leaving he gave them a great chest full of flax, and said, “Spin all of this before I come back.”

The princesses started to cry, “It’s too much! We’ll have to sit here the whole day every day to spin all of this!”

But the queen said, “Don’t worry. I will help.”

The queen knew that nearby lived three terribly ugly old maids. The oldest had a lower lip so large it hung down over her chin. The middle one had a forefinger as thick as three fingers on any normal woman. The youngest had a fat foot, as wide as half a kitchen table. The queen sent for these maids, and on the day the king returned they were sitting in the queen’s sitting room, spinning flax.

The king walked in and was happy to hear the humming of the spinning wheels, but he was was astonished to see the disgusting old maids. After a moment, he asked the oldest how she had gotten such a large lower lip.

“From licking the flax! From licking the flax!”

The king asked the middle one how she had gotten such a thick finger.

“From twisting the thread! From twisting the thread and wrapping it around!” she said.

Finally the king asked the youngest how she had gotten such a fat foot.

“From pedaling the wheel! From pedaling the wheel!”

The king was appalled. He ordered the queen and the princesses to never touch a spinning wheel again, and so they were delivered from misery and lived happily ever after. (Hassenpflug)

Okay, so it’s not the most politically correct of fairy tales, but you just know that any woman who told this story was self-identifying with the princesses, not the old maids, right? And it all works out great for them!

The Spinning Jenny

The beginning of the end of spinning came in the 18th century with another invention. As the story goes, James Hargreaves was a weaver in Lancashire, England. Like all weavers, he never had enough thread. He was a tinkerer, and he had previously experimented with adding a second spindle to a spinning wheel to get the same wheel to twist onto two spindles at the same time. It didn’t work. But in the early 1760s, someone knocked over a spinning wheel, and he observed that the wheel kept turning even when it was horizontal. It was a different configuration that solved everything. He tinkered some more and ended up with a spinning jenny. (A jenny was local dialect for engine.) With Hargreaves’s invention, a single worker could turn one wheel and twist eight threads at once (Finlay, 101).

An eight-fold increase in productivity is enormous, and later models pushed it to an eighty-fold increase. This was very, very good for anyone who wanted to buy cloth (everyone), and an absolute nightmare for anyone who made their living with a drop spindle or a spinning wheel (a whole lot of women). James Hargreaves moved his family and his patent to Nottingham after local hand spinners broke into his home and destroyed his machine and his furniture (Finlay, 101).

Matters only got worse for hand spinners when Richard Arkwright of Preston, England, invented a water-powered version and built a cotton mill. It was not the world’s first textile factory, nor even the first water-powered textile factory. But its predecessors in Italy and France had focused on silk, which was a luxury good. They couldn’t transform the world because most of humanity couldn’t afford their product. Hargreaves, Arkwright, and other English inventors absolutely flipped the world over by making cotton fabric cheap. That was something that had never before been true of any fabric in the whole history of world.

Cheap Thread Brings Social Consequences

It is no exaggeration to say that the British Empire got rich by putting the world’s spinners out of business. In earlier centuries, the English had eagerly purchased cotton cloth from India. In very short order, they stopped importing cloth and only accepted raw cotton. Demand outstripped India’s ability to grow cotton, so Brazil and the Caribbean and the American south got into the business of feeding English mills, with (if you know your history) some very serious social consequences. In return, England sold all of these countries finished thread and cloth at heavily marked up prices, while doing their very best to keep their technical innovations secret.

Of course, word got out. Mills were built elsewhere, but England had a solid head start.

As for the women who had previously done the spinning, they had to find other options. If they lived in the right places, some of them became millworkers. At the beginning they were excited about that. Compared to spinning all day at home under the watchful eye of your parents, a factory job felt like freedom. The problems became apparent later. If you didn’t live in the right place to work at a mill, you probably just got even poorer than you were before.

Some women used hand spinning as a form of protest. In the late 1760s, only a few years after Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, American colonists boycotted English goods and proudly declared they would spin their own thread after all. Even upper-class women started hand spinning, including some who had never done it before because they’d always had the resources to pay for some other woman to do it for them. Women would gather together for spinning bees and spinning matches to see who could spin the most (Ulrich, 182-191). I don’t know how much effect this had on British policies. I suspect it was more symbolic than anything else.

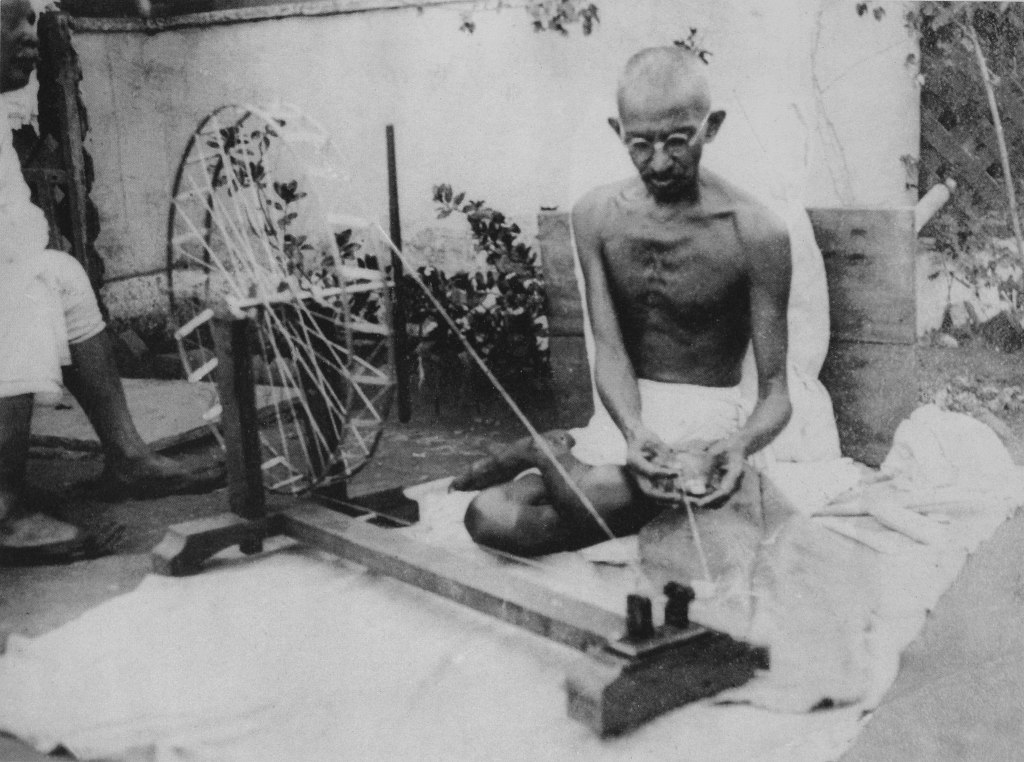

Nearly two hundred years later, Mahatma Gandhi also saw dependence on English cloth as a problem, and he had the same solution. He encouraged Indians to reclaim their past traditions and their current economy by spinning and weaving their own cloth, rather than purchasing the ready-made English versions. But what is nice is that he didn’t see this as something to impose on women. His wife Kasturba (episode 14.15) did spin cotton on a traditional Indian spinning wheel, but Mahatma Gandhi spun too.

Protest is all very well, but once independence is achieved, economic realities take over. Most people simply aren’t going to spin their own thread when they can buy better for less. American women gave up hand spinning again. By the American Civil War, only people living in the very poorest and most isolated communities wore homespun. Most people in India don’t wear it either.

However, interest in natural fibers and handicrafts has had a resurgence. As I said at the top of the episode, they’re not really natural fibers; they’re heavily bred. But they’re also not plastic. Interest in sustainability and ecological fashion is also growing. This means that if you would like to try spinning, you absolutely can. You can buy a drop spindle online. You can also buy your raw fibers, which may even come clean and carded, which was more than many a historical woman got. Some women nowadays describe the methodical rhythm of spinning as therapeutic.

My guess is that it can be as long as you’re not depending on it to buy you your small crust of bread at the end of the day.

If you have ever done any spinning, please comment down below about how it went.

I have a special thank you today to Roxi, who signed up as a supporter on Patreon. Supporters like Roxi keep this show rolling and freely available to everyone. If you’re able to help as well, I’d really appreciate it.

Bibliography

Beekaylon. “Gandhi and His Impact on Indian Textiles: A Legacy Woven in Khadi.” http://www.beekaylon.com, October 1, 2023. https://www.beekaylon.com/mahatma-gandhi-s-impact-on-indian-textiles-a-legacy-woven-in-khadi.

Finlay, Victoria. Fabric the Hidden History of the Material World. New York: Pegasus Books, 2022.

Hassenpflug, Jeanette. “Grimm 014: The Three Spinning Women.” sites.pitt.edu, n.d. https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm014.html.

McCune, Kathy. “How Long Does It Take to Spin Yarn? – Woolmaven.com.” Woolmaven.com, March 5, 2023. https://woolmaven.com/144/how-long-does-it-take-to-spin-yarn/.

Postrel, Virginia I. The Fabric of Civilization : How Textiles Made the World. New York: Basic Books, Hachette Book Group, 2020.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. The Age of Homespun : Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. New York: Vintage Books, 2001.

Yashuv, Talia, and Leore Grosman. “12,000-Year-Old Spindle Whorls and the Innovation of Wheeled Rotational Technologies.” Edited by Iris Groman-Yaroslavski. PLOS ONE 19, no. 11 (November 13, 2024): e0312007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312007.

My dad owns a spinning wheel, carders, and a drop spindle. He has wanted his own loom for years, but can’t justify the space. He has woven small rugs in the past, but isn’t interested in crocheting or knitting. My mom crochets, but never with Dad’s thread/yarn.

LikeLike

(That was Kate the Great.)

LikeLike

[…] products we now use for diapers didn’t even exist for most of human history. As I discussed in episode 15.4 on spinning, cloth was unbelievably expensive for most of human history. So the solution to a baby’s sanitary […]

LikeLike

[…] create. Clothes were expensive. They had become much less expensive with 18th century inventions in spinning and weaving, so by 17th century standards, they were cheap. But those early inventions did not help […]

LikeLike

[…] full discussion of its own, but even so, I covered only one major invention from that time period: the spinning jenny. That alone was enough to put Britain right at the top of world dominance, and of course they […]

LikeLike