In 1869, the English essayist William Rathbone Greg wrote a little piece called “Why Are Women Redundant?” and the title alone is proof that he badly needed an editor. Upon reading his essay, it becomes clear that Greg does not believe that all or even most women are redundant. Married women are fulfilling the purpose for which women exist, so they’re all right. Greg is also okay with single women in domestic service. Servants “discharge a most important and indispensable function in social life; they do not follow an obligatorily independent, and therefore for their sex an unnatural, career … they fulfil both essentials of woman’s being: they are supported by, and they minister to, men” (Greg, 25, italics original).

(I am immediately wondering about all the maids who were actually employed by women, and wondering if that makes them redundant after all, but Greg does not grace us with his opinion on that issue.)

Greg’s also okay with lower class single women working in factories. “Women and girls are less costly operatives than men: what they can do with equal efficiency, it is therefore wasteful and foolish to set a man to do” (Greg, 33).

The women Greg has a problem with are the middle and upper-class single women. Those who subsist on the charity of their male relatives, and when that fails, go out to become destitute needle women or third-rate governesses. These are the women who are contributing nothing to a society newly inspired by notions of progress and productivity. They also suffer themselves because, in the words of Greg, “in place of completing, sweetening, and embellishing the existence of others, [they] are compelled to lead an independent and incomplete existence of their own” (Greg, 5). They are superfluous.

Greg, and others like him, were concerned because recent British censuses showed such women to exist in alarming numbers. They far outstripped the number of single men. By his calculations the United Kingdom had 1,100,000 women who were “unnaturally” single (his word, not mine).

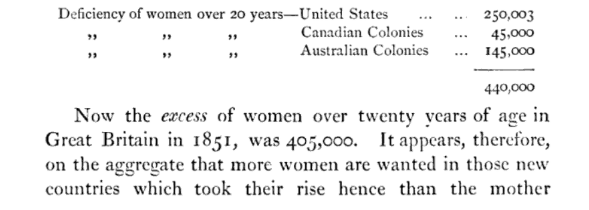

Greg’s essay proposed a plan to mitigate this. He did a lot more fancy calculations, and it came to his attention that this state of affairs was reversed in other places. He claims that the Canadian colonies ran a deficit of 45,000 adult women. The Australian colonies needed 145,000 women to break even. And the United States would be happier with 250,003 additional adult women. I’m not sure why the United States needed precisely three women beyond the nice round number, and this is another case where Greg needed an editor because he totaled those numbers and forgot about the three, making it 440,000 redundant women who simply needed to emigrate from Great Britain to the colonies and former colonies. Voila, they would no longer be redundant (Greg, 14).

Greg anticipated potential objections. The first one on his mind is simply that moving 440,000 women across oceans is a logistical challenge. He thinks that the combination of private charities and government intervention could fix that (Greg, 17). The second problem was that the class of women wanted in the colonies (i.e., good hard workers like dairy maids) was not the same as the class of women redundant in the Great Britain (i.e., educated spinsters who were brought up to believe working in a dairy was beneath them). To this he says merely, ladies, give up your pride and remember that your education confers adaptability (Greg, 18-19).

All in all, Greg’s essay is as full of holes as the Swiss cheese those dairy maids might have been making, but he was not alone. He was part of a debate that lasted for decades on what to do with single women who could not support themselves.

It was hardly a new concern. Jane Austen wrote about the same issue decades earlier, but the answer then had always been that some male relative must provide, however grudgingly. Failing that, the woman simply sank in social status, and frequently she sank to the very, very bottom. But throughout the 19th century, the numbers and visibility of these women increased. Hence the debate. Meanwhile, the women who actually did emigrate were mostly lower-class. And you can see why. They had far less to lose. They would probably end up doing similar work in either country, but wages were typically better overseas, for the simple reason that labor was in short supply. Wives were in short supply too, so they’d soon get married, and give up the job, in favor of similar work in their own homes for no pay at all (Levitan, 366).

The Feminist Response

As you can imagine, the burgeoning feminist movement did not agree with Greg about the proper remedy to any of these problems. Their solution was that we should enable middle and upper-class single women to support themselves and be productive members of society. What a thought!

Feminist Frances Cobbe wrote a response essay to Greg’s essay. She entitled it “What Shall We Do with Our Old Maids?” and she agreed with Greg that:

“Marriage is, indeed, the happiest and best condition for mankind. But does anyone think that all marriages are so?… Do we mean a marriage of interest, a marriage for wealth, for position, for rank, for support? … Such marriages as these are the sources of misery and sin, not happiness and virtue” (Cobbe, 62).

In short, she continued, the best way to promote happy marriages was to make sure that single women were healthy, happy, and fully employed, so that if they did marry, it was from choice, not from desperation. She is particularly interested in women as doctors, and she goes on at length about why that’s a good idea. At the time, no British woman had ever qualified as a doctor.

Fellow feminist Jessie Boucherett went even farther and suggested that maybe men should emigrate. Then the women back at home could step into their jobs. There would be millions of single women, but not one would be superfluous, “as every one would be valuable in the labor market” (Boucherett, 33)

According to Greg, women as professionals was a terrible idea. Those wild schemers “who would throw open the professions to women, and teach them to become lawyers and physicians and professors, know little of life, and less of physiology… The cerebral organization of the female is far more delicate than that of a man… Mind and health would almost invariably break down under the task” (Greg, 32).

In other words, the physiology of women was perfectly adequate for hard labor like laundry, milking cows, and hauling water. Working class women were doing that already even in Great Britain, and Greg was suggesting that middle and upper-class women could do the same in the colonies. But those same women’s physiology was inadequate for cerebral pursuits, rather than physical.

This argument is so ridiculous, it would be funny, if it hadn’t been so deadly serious for so many Victorian women. It wasn’t simply a matter of whether these women felt useful and appreciated, or even in whether they could feed and clothe themselves. The question of superfluous or redundant populations was part of the larger eugenics movement and the idea that it was best for humanity as a whole if it purged the “undesirable” elements of society, whether they be single women, or the disabled, or the indigent poor, or suspected criminals, or the LGBT, or certain racial, ethnic, or religious groups. In the end, I wouldn’t say that middle and upper-class women paid the heaviest price here, but in 1869, they didn’t know that. Many eugenic horrors were still in the future.

The Middle Option

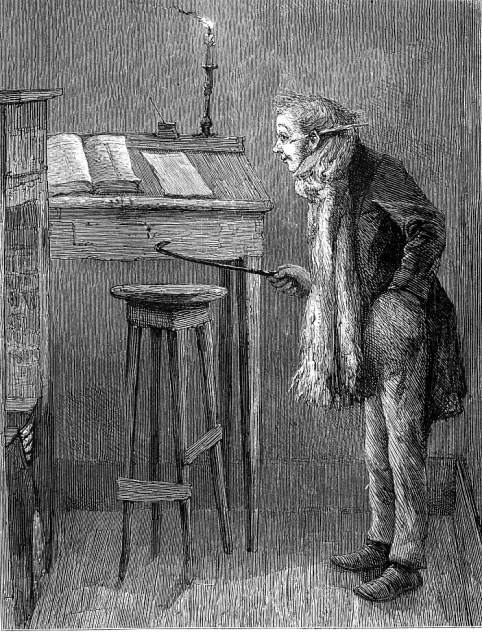

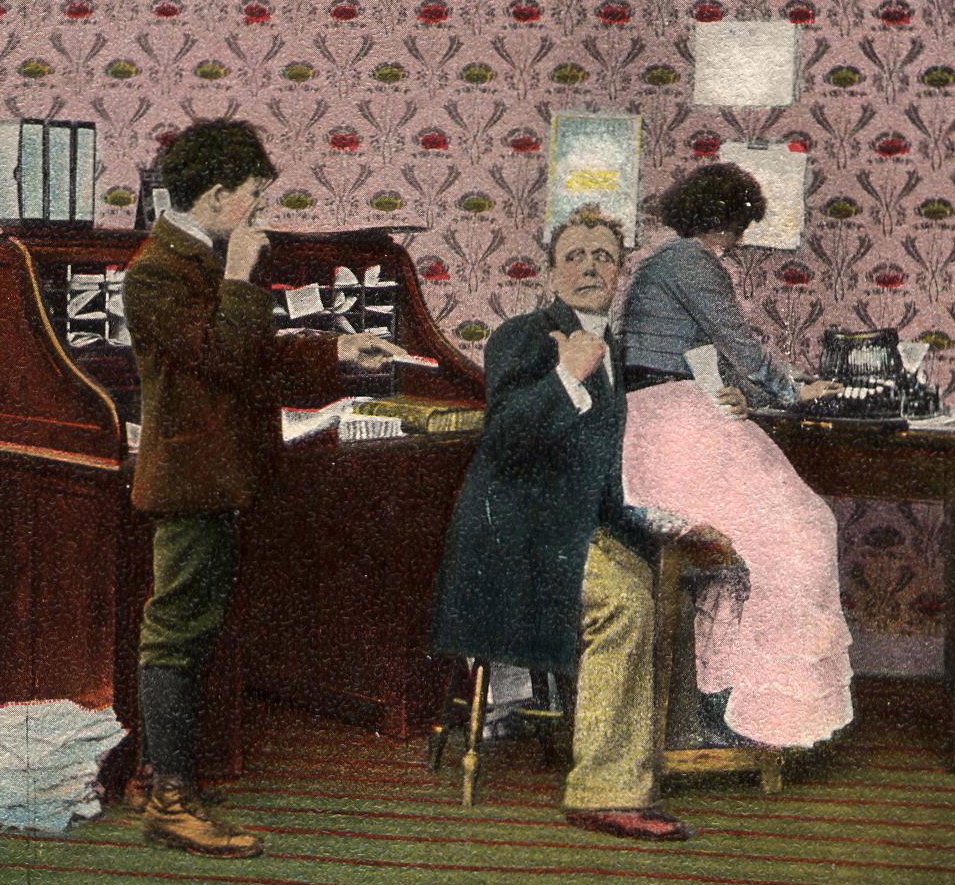

Now obviously, women should have been allowed into high prestige jobs like lawyers, doctors, and professors. But there was also another kind of white-collar job, and that was to be a clerk or secretary. Nowadays the stereotypical image of a secretary is definitely a woman, but that was not the case in the 19th century. The most famous literary figure in this role is a man: it’s Bob Cratchet, who works for Ebenezer Scrooge in The Christmas Carol. Cratchet is poor and underpaid in the story, but that is in part because his salary has to cover the expenses of a family.

For many a single woman, with only herself to support, it would have been a dream job, allowing her to live independently and dispense with the grudging support of a male relative. And like so many dreams, it was largely out of reach. Though many, many women now had the requisite reading, writing, and arithmetic skills, they were not acceptable in the offices of an economy that was growing more and more dependent on bureaucrats rather than farm laborers. Partly this was because they would take jobs from men, and no one wants more competition. Partly it was because offices buildings literally didn’t have the infrastructure for women: they had no toilets for women (Connolly).

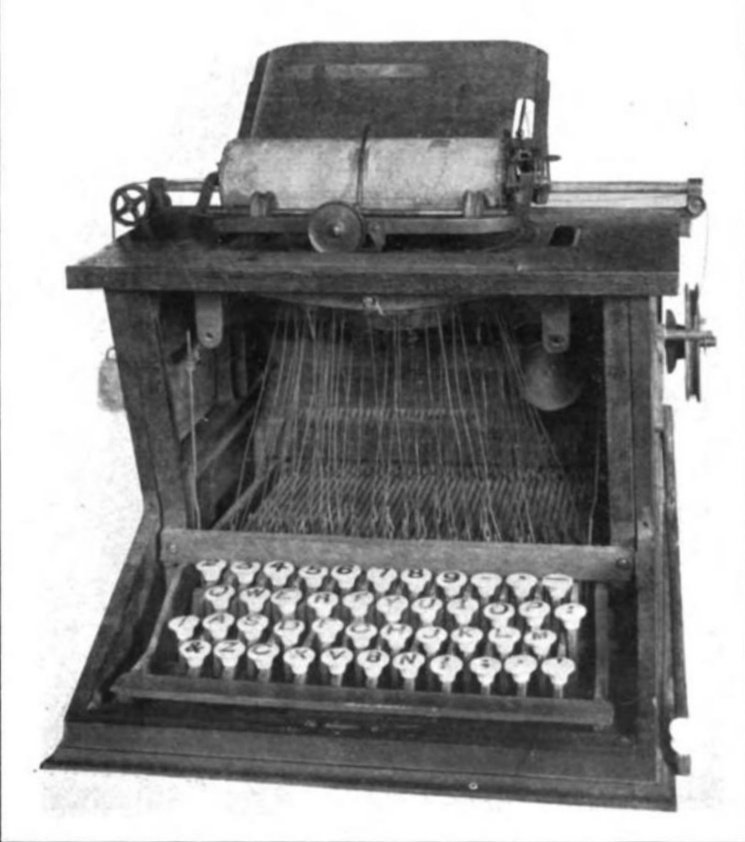

It seemed unlikely that women would ever crack the door into the business office, but then something unexpected landed in the middle of the debate. In 1868, American inventor Christopher Latham Sholes patented a brand-new machine: a typewriter.

It was not the first attempt at such a device, but it is the one that he sold to a company named Remington. It took Remington a bit to get it on the market, but on July 1, 1874, it went on sale to the public. It was substantially different from what you might be imagining. For one thing, it was “blind,” a term they used to mean that the operator could not see the text as it was being printed, so you wouldn’t notice any typos until later. Also, it could only print capital letters. Also, it was built into a sewing machine base, and you used a foot treadle to return the carriage at the end of each line (Hoke, 77). In other words, there was room for improvement.

Which Remington did. Among other things, by 1875, Sholes had also innovated the QWERTY keyboard layout that is still used by many English speakers on their laptops and smart phones even today (Simon). By 1882, competitors had also gotten into the game (Hoke, 77).

Women and Typewriters

Sholes likely had no idea how much his invention would change life for women. Certainly, Remington did not. Their early ads suggest that they didn’t even realize that businesses should be their target audience. They thought of this machine as an aid to literary writers. The ads showed women in poses suggesting that girls who aspired to be Jane Austen or Harriet Beecher Stowe would buy this so they could type up their novels at home (Hoke, 83). So yes, it was feminine, but business, it was not.

However, businesses on both sides of the Atlantic were thrilled with the possibilities of the typewriter. In competitions, speed typists generally defeated speed writers by about 30 words per minute (Hoke, 78). The only trouble was that the Bob Cratchets of the world did not know how to use it. Therefore, offices now had job openings, and it wasn’t a matter of women coming in to compete with men for the job. Rather, it was a matter of women coming in to do a job that previously had not existed. That was more palatable than the wild schemes of people like Frances Cobbe (Waller, 46; Hoke, 81).

There were a few other reasons offered for why this was appropriate women’s work. Remington was a company already familiar to women because they made sewing machines, and the comparison between the two machines was repeatedly brought up. One ad also drew attention to the comparison with another skill that many women had, by saying it involved “no more skill than playing the piano” (Keep, 405). Which speaking as a pianist, leaves me baffled. Playing the piano takes a lot of skill but theoretically, women’s fingers were smaller and more delicate and better suited. Hours of knitting and sewing and left their hands with fast and accurate fine motor skills (Rimkunas; Keep, 405).

Maybe so, but the main reason was that women were willing to do it for less money than men. This made it worth it for business owners to swallow their scruples, install a women’s toilet, and move on. Women were willing to take less money because even at half the wage of their male counterparts, it was still significantly more money than they could make in a factory or in domestic service, and it had more prestige too (Hoke, 79; Keep, 403).

Some of them were honest about other reasons too. For example, women were less likely to unionize and demand higher wages (Conolly). And they were no threat at all as future competition, since they couldn’t rise to the higher echelons of the company. All in all, businesses decided they liked having a few women around, so long as they stayed in their proper place.

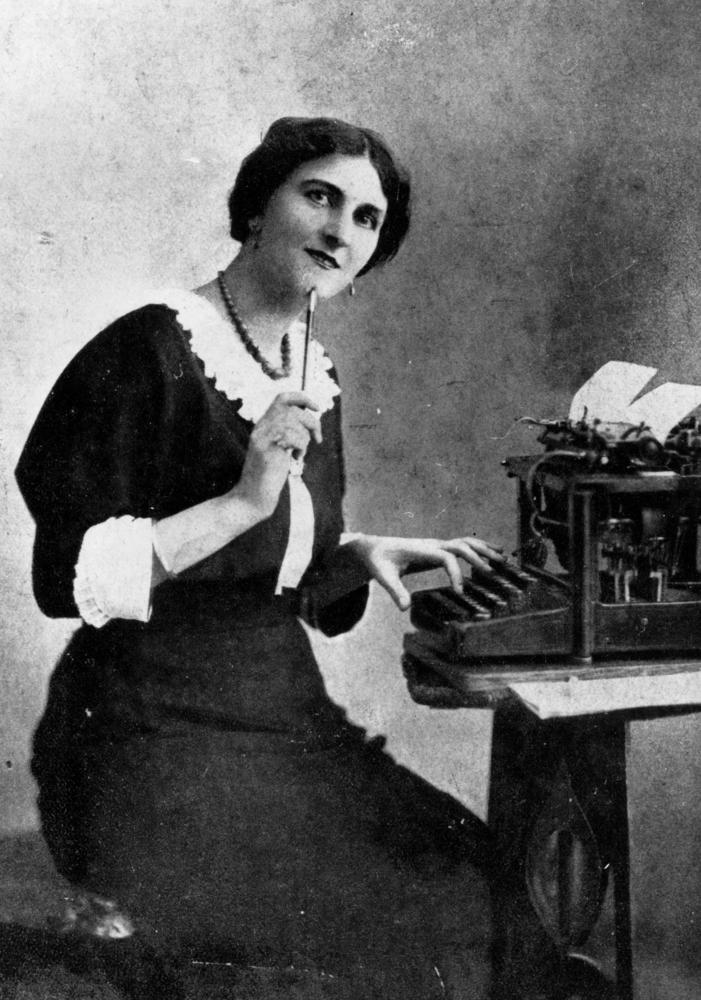

The Typewriter Girl

By the mid-1880s, men do not even appear in ads for typewriters. All the typists are women (Hoke, 83). The stereotypical image of low-level office personnel had completely shifted. A stenographer is someone who takes down spoken language verbatim into written form. It’s particularly important in court proceedings, but also in business transactions. When this was done by hand, many women had the requisite skills, but somehow they largely didn’t get the job. In 1870, only 4.5% of the stenographers in the US were women. By 1900, 76.7% of them were women. Not only that but the sheer total numbers had exploded. The industrial age was expanding business opportunities, the typewriter was expanding business communications, and women were doing the typing (Hoke, 77).

To do so, women needed training. The first typing school was established by the Young Women’s Christian Association (or YWCA) in New York in 1881. Remington’s competitors weren’t even on the market yet, and the general public was not yet convinced that this was appropriate for women. “Well-meaning but misguided” was what commentators said. Nevertheless, the eight women in the first graduating class did well (Hoke, 79-80; Keep, 402). They were succeeded by millions of others. Remington wanted to expand overseas, but they could hardly sell a product that no one knew how to use. So they opened up typing schools on every continent except Antarctica to fill the gap and create the customer base (Keep, 406). By 1889 there was a methodology involved. It wasn’t just hunt-and-peck; it was use all ten fingers and keep your eyes on the paper, not the keyboard (Waller, 43).

The women taking these courses were mostly from the middle class. They had to be to have the literacy skills and the ability to take a 6-month course at the YWCA. They were also mostly young. The average age of what came to be known as a Type-Writer Girl was generally between 20 and 30. They didn’t rise higher because they mostly quit when they got married. And most of them did get married, relieving anyone’s worries about superfluousness.

In fact, the Type-Writer Girl was glamorous. To be young and in possession of your own money, and yet still have leisure and independence to enjoy an evening out or an outing on Sunday? This was a new concept to a large number of women. The typewriter girls in the ads were always fashionably dressed. In fact, they dressed better than your actual typewriter girl could afford. The pay was not high. It was just higher than in the factory or domestic service.

Businessmen found themselves to be in no way averse to having young, pretty, and attractively dressed young women around the office. It likewise became a way for a middle-class girl to acceptably meet middle-class men, one of which might fall in love with her. In fact, it became a standing joke for vaudeville routines to have a typewriter girl who married her boss (Keep, 416; Waller, 44).

As you can well imagine, this was a situation ripe for sexual harassment and abuse. Which is exactly what happened. As sad as that is, it did not prevent most women from choosing it, for the simple reason that their other options were no better. Harassment of the domestic servants has been going on since domestic servants came into existence, and it happened in factories as well.

The fact was that while typewriters promised women independence, they did not fully deliver. Girls might be more independent of their fathers, but they were not any more independent of men. Getting into the office was one thing. Moving up in the office was something else. Nevertheless, the typewriter opened a door that had been quite firmly closed. The typewriter is what made it respectable for a middle-class woman to work outside her home at all.

Because she’s not superfluous.

If you liked this article, please consider supporting the show, either with a one-time donation or as a regular subscriber with benefits like ad-free episodes and bonus episodes.

Selected Sources

Boucherett, Jessie. “How to Provide for Superfluous Women.” In Woman’s Work and Woman’s Culture: A Series of Essays., edited by Josephine E. Butler. London: MacMillan, 1869. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011618602.

Cobbe, Frances. “‘What Shall We Do with Our Old Maids?’ Fraser’s Magazine (1862, Reprinted as ‘Essay II’ in Essays of the Pursuits of Women 1863) .” Archivalgossip.com, 2021. https://archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/632.

Connolly, Hannah. “Holding the Keys – How the Typewriter Shaped the Workplace for Women.” Thestack.world, 2021. https://www.thestack.world/news/society/people/holding-the-keys-how-the-typewriter-shaped-the-workplace-for-women-1628258839918.

Greg, William Rathbone. Why are Women Redundant? United Kingdom: Trübner, 1869. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Why_are_Women_Redundant/R0aQ36xR1sAC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Hoke, Donald. “The Woman and the Typewriter: A Case Study in Technological Innovation and Social Change.” Business and Economic History 8 (1979): 76–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23702593.

Keep, Christopher. “The Cultural Work of the Type-Writer Girl.” Victorian Studies 40, no. 3 (1997): 401–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3829292.

Levitan, Kathrin. “Redundancy, the ‘Surplus Woman’ Problem, and the British Census, 1851–1861.” Women’s History Review 17, no. 3 (July 2008): 359–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612020801924449.

Rimkunas, Barbra. “How the Typewriter Brought New Opportunities to Women .” Exeter Historical Society, April 7, 2024. https://www.exeterhistory.org/historically-speaking/2024-03-15/typewriter-revolution.

Simón, Yara. “The History of the Typewriter.” HowStuffWorks, 1970. https://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/inventions/typewriter.htm#pt1.

Waller, Robert A. “WOMEN AND THE TYPEWRITER DURING THE FIRST FIFTY YEARS, 1873-1923.” Studies in Popular Culture 9, no. 1 (1986): 39–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23412899.

[…] Of course, most women didn’t see that kind of success. But their mastery of the home sewing machine proved one thing: Women were perfectly capable of operating a complex machine. You might think that was obvious, but it wasn’t obvious to a lot of people in the 19ᵗʰ century. The sewing machine was the first complex machine available to such a large section of women. And they did just fine with it. And later on their sewing skills were considered directly applicable when another new machine became available: the typewriter. And that machine opened up the world of business offices to them. (See episode 15.5.… […]

LikeLike

[…] she wanted an office job, she could have taken a typing course and learned to type, thus entering a business world that had previously only existed for men. If Mary herself felt too […]

LikeLike