Close your eyes. Take a mental walkthrough of your home, and count up how many places in it provide water. I’ll wait.

I live in an American suburban house. It’s not very big by American suburban standards (which, I admit, are ludicrous). My upstairs bathroom has a sink, a bathtub faucet, and a shower head. The downstairs bathroom has a sink and shower head. Each bathroom also has a toilet (which I admit I didn’t initially think of as a water source, but technically, it is). The kitchen has a sink and a fridge that dispenses both water and ice separately. The laundry room has a hookup for the washing machine, and there’s a hose in the front yard and another in the backyard. That’s thirteen places I can go to get water, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Most of those places can dispense hot or cold water, whichever I want, and two of them are cold and really cold by design.

That is a miracle, folks. An absolute miracle. Most historical women would simply not have believed this was possible.

The story of how and when it became possible is a little murkier than I would like. I had lots of sources on how humanity has managed water, but they tend to be focused on the macro scale. They tell you how to water a massive slave-tended field, but I was more interested in how your average woman managed when she needed to thin out the evening soup to feed another person and wash the dishes afterwards. Sources aren’t so good on stuff like that.

How Much Water?

According to the EPA, the average American uses 82 gallons of water at home per day. Probably because most of us find it so easy to get. I’m not particularly careful because I’m living with thirteen taps and a climate that generally complains about too much water, rather than not enough. Like everyone else, I use water for drinking, cooking, washing myself, washing my kitchen, washing my clothes, and washing anything else that needs washing, especially in the bathroom. I might be more careful if I had to haul every one of those gallons myself, some of them both in and out of the house. That’s another important point. Most of my thirteen water sources come with a handy drainpipe attached.

Incidentally, water is heavy. Each gallon weighs over eight pounds (almost four kilos). Multiply by 82, and you get a good, solid amount of lifting.

You might think that the ideal solution, other than having modern plumbing, is to situate your house so that your water source is basically in the front yard. But that gets tricky. Sure, it’s good for your daily water haul. But waterfront properties often have problems with diseases and insects, and they really have a problem with floods. Balancing these competing concerns has been a struggle for every sedentary population ever. How well they handle it has been literally the difference between success and failure, between life and death.

One solution is to simply walk to your water source and fill up your waterproof container (which, incidentally, is a miraculous invention in and of itself). Then you carry your container back. All 8 pounds per gallon of it. This leaves very little trace in the historical record, but we know someone must have done it. The actual source of the water might be a river or a lake, but it also might be a well. Wells are the only hope of evidence we have, and sure enough, we find them to be considerably older than most other evidence of civilization, clocking in at 8500 BCE on Cyprus (Dawson), and elsewhere over the next few millennia. Some of those ancient wells are still working wells.

Women’s Work

Carrying water is so mundane that it rarely got written down at all, but we can deduce that it was woman’s job from several sources, including the Bible. When Abraham wanted to find a wife for his son, he sent a servant to a well. Apparently, the servant could not or would not draw water for himself, so Rebekah did it for him (Genesis 24). Hagar was cast out with her son until God provided a well for her, where she drew water (Genesis 21). Several thousand years later, Jesus visits a well and asks a Samaritan woman to draw a drink for him (John 4).

Things were no different around the world and two millennia later. In 1886, a North Carolina Farmer’s Alliance organizer was looking for an issue that would attract women into the organization. What he landed on was water. He chatted with one man who lived sixty yards from a very good spring. The organizer wanted the man’s wife to join too, so he whipped out a pencil. He assumed that water had to be brought into the house six times a day on average. “Well, suppose we figure a little,” he said. “Sixty yards at six times a day is 720 yards—in one year it amounts to 148 miles and during the forty-one years that you have been living there it amounts to 6,068 miles—don’t you think we could get up some question that would interest the farmers’ wives and daughters? Remember too that half the distance is up hill with the water” (Strasser, 86).

This doesn’t precisely say that the man of the house never carried the water, but it certainly assumes that it was mostly the woman. That was the cultural expectation.

In sub-Sarahan Africa, it is still the cultural expectation. A 2016 study interviewed families that walk for water more than 30 minutes a day, across 24 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In Cote d’Ivoire, for example, it was a woman 90% of the time. That was the highest percentage, but only Liberia had adult women doing it less than 50% of the time. You might think that means that men are doing it more than 50% of the time in Liberia, but in that you would be wrong. Because when it isn’t done by an adult woman, it’s usually done by a child. (Liberian men did it in just 15% of the households that needed it.) Oh, and surprise, surprise, it is more likely to be a female child than a male child (Graham).

I cannot prove that what was true in ancient Israel, 19th century rural America, and modern-day sub-Saharan Africa was equally true in all historical societies. As I said, the records are mostly silent. But I can’t think of any good reason to doubt that it was true for many of them. Historical woman carried an awful lot of water.

Carrying the water frequently has a physical impact on health. And it’s also just a time drain. Every minute you spend balancing a jug of water on your head is a minute that you aren’t going to school, aren’t building a small business, aren’t improving your house, and a thousand other things. So when alternatives existed, it must have been a huge relief to women in particular.

Ancient Inventions and Water

Given how many women still don’t have these alternatives, you might be surprised at how early they show up, at least for rich people. The Indus Valley civilization dates to 2500 years BCE and is located in modern-day Pakistan and India. In their two big cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro almost every house had a private bath and toilet, with drains to take wastewater out to a larger drain for the neighborhood (Antoniou). The drains were made of baked bricks (another invention), made waterproof with a mud mortar, and placed under the streets. Fun fact for you, this drainage system still works. In 2022, the area had torrential rainfall. Mohenjo-daro handled it just fine, thanks to a piping system that is 4500 years old (The Friday Times).

Getting the dirty water out is super important, and well beyond my personal engineering skills, but still seems to me to be relatively easy compared with getting the clean water in. I am not at all clear on how Indus Valley baths and toilets were supplied with water. Having a drain is not the same as having a faucet or tap.

Over on the island of Crete, some lucky Minoan woman lived in the Queen’s Megaron in the palace of Knossos. (At least, the original excavator called it the Queen’s Megaron. I am unsure how he knows it was the queen’s and not the king’s, but whatever.) It featured, among other things, a terra-cotta bathtub and what may be the world’s first flushing toilet (Banda). But don’t get too excited because the water for flushing wasn’t piped in. You literally poured the water from a vessel to make it flush. The vessel might have been collecting rainwater, which is easy, if unpredictable. But it also might mean that someone carried that water in. I’m guessing it wasn’t the queen.

Eventually, multiple places independently figured out enough hydraulic engineering to come up with piped-in water. Maybe not on the scale that you are thinking, but the ancient world had continuously flushing toilets. That means there was no lever to push when you want to flush. There was just a continuous flow of water that carried waste away. This existed in Japan and Greece and most famously in Rome (Antoniou).

Romans and Water

Romans knew about several simple machines that can transport water. Archimedes’s screw is named after the Greek writer who described it, but it’s actually an Egyptian invention. Basically, it’s a tall cylinder with a spiral or helical surface going around it. If you turn the central cylinder, the helix picks up water at the bottom and carries it to the top. The principal is still alive and well in modern engineering.

However, Romans primarily just used gravity. Starting in 312 BCE, they found springs in the valleys and highlands around the city and built a carefully graded system of aqueducts and conduits down into the city. It could even go underground and come back up because the constant influx of new water into the system built up the water pressure so that it flowed back up into the fountains in every part of the city. Pipes were usually made of lead. So that’s sketchy, but sometimes of they were ceramic, wood, or even leather (Havlicek, 35).

This does not mean that your average Roman woman got thirteen water sources in her own house. It does mean that your average Roman woman could get a bath without hauling any water. That’s because she didn’t bathe at home. Instead of hauling water, she hauled herself to the public bathhouses, which did have constantly flowing water.

Your average Roman woman didn’t need water for cooking at home either. That’s because she had no kitchen facilities. Partly this was about water access, but mostly it was about fire danger. In a densely urban environment, you really don’t want everyone constantly cooking over an open flame. Most Romans ate from street vendors or in taverns.

For her other water needs, your average Roman woman went to the public fountains. And if she didn’t want to use it right there in public, she must have carried it back home.

As for getting rid of the wastewater, Rome had a goddess of sewers! Because why not have a sewer goddess? Cloacina presided over the Cloaca Maxima, which translates to Greatest Drainage. It began early in Rome’s history and grew over time, eventually carrying much of the city’s wastewater out into the Tiber river. Parts of it are still functioning even today.

Again, this does not mean that your average Roman woman had access to drains in her house. The state (sometimes) maintained the main drains, but they did not hook up individual houses. If you were wealthy, you paid for that yourself (Havlicek, 363). You also paid to be hooked up to the aqueduct, so you got private baths and kitchens with piped-in water. As always, it pays to be rich.

Romans exported similar systems all over the empire, so you didn’t necessarily have to be in Rome itself to enjoy these benefits. Romans congratulated themselves on bringing water and civilization to the savage masses and rarely paused to wonder whether those people would have chosen freedom over plumbing if they’d had the choice. We’ll never know because the records are all written by Romans.

Then the empire collapsed and so did the building of new large-scale waterworks. It’s really only possible with a strong central power. Some survived, as I said, but overall, Europe would not enjoy infrastructure that good until the 19th century (Boccaletti, chapter 6). Elsewhere in the world, strong central powers were alive and well, and they had waterworks to prove it: Baghdad, Han dynasty China, the Maya at Palenque, the list goes on. If I’m saying little about these places, it’s because the details of how ordinary women accessed it (if they accessed it), are just not included in my sources.

Small-scale waterworks were alive and well, even in medieval Europe. Contrary to what you might have heard, there is plenty of artistic evidence of bathing in the Middle Ages (Medievalists.net).

Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms-5221 réserve, fol. 287r.)

But as far as I can tell, there is not much evidence of how the water got into the bathtub. Or anywhere else. One suspects that it varied, depending on where you were, when you were, who you were, and how much you could pay. For example, in the 13th century, the City of London built a Great Conduit that piped water from Tyburn Springs nearly three miles into the heart of the city where people could fill their own containers. It worked right up until the Great Fire of London destroyed it in 1666. None of my sources really explains what women did after that. Presumably, they just walked farther.

Rebuilding the Waterworks

Large-scale public waterworks came into their own again in the 19th century. In part, this was because an increasingly urbanized world simply couldn’t live without a centralized water system. When large numbers of us are living cheek by jowl, we can’t all keep our jowls right next to the river, and we can’t all dig our own wells either. Cities installed pumps or fountains at regular intervals. Which is a big help, but still not the same as installing thirteen taps in your own house. They also installed drains for pouring out your wastewater, and those might be much closer to your house.

In the United States the city that pioneered waterworks was Philadelphia. Their system opened in 1815, and they used pumps and gravity and surplus reservoirs to build a system that was a marvel to visitors like Charles Dickens. Only subscribers got the water directly into their homes, which meant in the early part of the 19th century, most people still used private wells or the street hydrants. Other cities followed Philadelphia’s lead. If you were out west, you were not so lucky, but sometimes your municipality would hire a wagon to drive around town and deliver water to private tanks (Strasser, 92,93).

Not everything about public provided water was good. Quite the opposite. This became absolutely crystal clear through the work of Dr. John Snow in London. He was dealing a cholera outbreak in 1854. Cholera is a disease in which you basically vomit and diarrhea until you are so dehydrated that you die. At the time, it was believed that this was caused by bad air, and since you can’t really do much about breathing, it was hopeless. You were doomed.

Dr. John Snow wasn’t so sure. He very carefully mapped each home suffering from cholera, and he proved that they were all getting their water from a particular pump. Snow did not know if the newfangled germ theory of disease was true or not, but he knew a real easy way to test his theory. He convinced the local council to remove the handle from the pump. People had to go farther for their water. But they didn’t get cholera (Boccaletti, chapter 11).

We now know that bad air has nothing to do with cholera. Cholera is caused by a water supply contaminated with sewage. Modern waterworks are very careful to make sure that sewage going out does not mix with the water coming in, but a lot of people died before we figured out how important that is.

As usual, it was only the rich who successfully got water directly into their house. One woman who tried was Harriet Beecher Stowe. In 1850, before she was rich and famous, she rented a house in Maine, and she wanted an indoor sink with a water pump, but there were no pipes of any kind. Undaunted, she purchased two very large barrels to use as cisterns, only to find that they would not fit through the door. She wrote to her sister that “In the days of chivalry, I might have got a knight to make me a breach through the foundation walls,” but those days were over. Finally, she hired a cooper to take the barrels apart and reassemble them inside. But still all was not well. The landlord refused to install her sink (Strasser, 97). I’m unclear on whether she ever got running water in this house.

Indoor plumbing did not become commonplace in the United States until decades later, when Progressive reformers (most of them wealthy or middle class) entered the living quarters of the poor and were appalled by what they found. The poor were dirty and unsanitary, just like elitist complainers said they were. But it wasn’t because the poor liked being that way. With no water supply in the house, inadequate supply out of the house, and long working hours that left them too exhausted to do the additional exhausting job of carrying water, the poor literally didn’t have the resources to be clean.

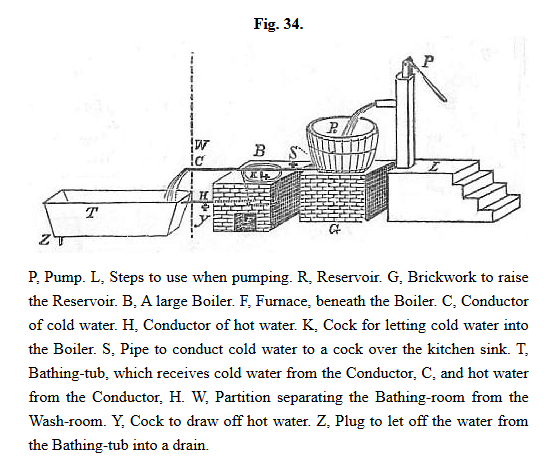

By this point, it wasn’t because the US didn’t have the technology to provide water. They did. It just cost money, both to install and to maintain. Catherine Beecher, for example, was a fabulously successful 19th century influencer, who told women how to manage their households and lives. Her 1848 book on domestic economy includes a plan for pump for household use. It assumes that you have a well or cistern under your house. The pump should be used once a day to fill a more accessible reservoir. She says should be done by a man or boy! I approve this message.

After that, the woman of the house has taps that she can turn to let the water flow from the reservoir into a bathtub, or into a boiler which heats the water before flowing it into the bathtub or into the kitchen sink. This she says will allow you to use great quantities of hot and cold water with “no labor in carrying and with very little labor in raising it” (Beecher, Treatise, chapter 24). All well and good, but of course it wasn’t really as easy as that. For one thing she elsewhere admits that “the plumbing must be well done, or much annoyance will ensue” (Beecher, American Woman’s Home, chapter 2). And for another thing, Beecher’s audience was middle class. The lower classes could never have paid for such a system.

One obvious solution would have been to do what the Romans did. Make it more affordable by making public bathhouses, which are easier to supply with water than each and every small tenement home. In 1891, New York City did open public bathhouses. It enjoyed some limited success, but it didn’t really catch on. In part that was because social reformers always spoke to poor people with a healthy dose of paternalistic lecturing (Blakemore). The poor didn’t really like it. I’m guessing that heading to the public baths came with the same kind of insecurity that some of us feel when heading to the gym. You’re there to improve yourself, but somehow, you already feel judged for needing improvement. It’s easier to just stay home.

Water in the 20th and 21st Centuries

As late as 1919, this was still a big problem, and the idea of public baths was no longer considered the answer. One social reformer that year dreamed bigger. She said “There should be toilet facilities in good condition with a door which can be locked, for the use of the family alone; running water in at least one room in the house besides the toilet… A bath room is highly desirable and should be included wherever possible” (Strasser 100).

It was not until the 1920s that indoor plumbing stopped being a luxury item. Even then, most of you would be very dissatisfied with what the poor had. Perhaps a shared bathroom for a whole floor of apartments. Or bathtubs with only a cold water tap. Or pipes that froze in the winter which meant you didn’t actually have running water after all (Strasser, 102). And I’m still talking about the United States here. The rest of the world came along at their own pace, sometimes quickly and sometimes … not.

All in all, it took most of human history and many inventions to get to the point where most (but not all) of us just expect to have running water close at hand, pretty much wherever we go. I’ve spent virtually none of my life carrying water. Building codes don’t permit buildings that don’t have water. Which has certainly improved the standard of living for many of us and allowed for unbelievable displays of conspicuous consumption like thirteen taps in one house. Sheesh.

The flip side is that even today, even in first-world countries, not everyone can afford this. Homes are much more expensive than they used to be, and one of many reasons for that is that homes used to be basically just a box with a door. No plumbing, no electricity. You can see how that would be cheaper. One perennial suggestion about the homeless problem is that if we relaxed building codes, housing wouldn’t be so expensive and more people could afford it, especially in emergency situations (Valdez). Surely four walls and a roof with no water source is better than no walls, no roof, and no water source?

On the other hand, we really, really don’t want to go back to the tenement slum situation. I have no answers on public policy debates. This is why I’m a podcaster, not a public policy maker.

If you liked this article, please consider supporting the show, either with a one-time donation or as a regular subscriber with benefits like ad-free episodes and bonus episodes.

Selected Sources

Antoniou, Georgios P., Giovanni De Feo, Franz Fardin, Aldo Tamburrino, Saifullah Khan, Fang Tie, Ieva Reklaityte, Eleni Kanetaki, Xiao Yun Zheng, Larry W. Mays, and et al. 2016. “Evolution of Toilets Worldwide through the Millennia” Sustainability 8, no. 8: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080779

Banda, Austin. “The Queen’s Megaron at Knossos: A Pleiades Location Resource.” Pleiades: a gazetteer of past places, 2020. https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/271668241/the-queens-megaron-at-knossos.

Beecher, Catharine Esther. A Treatise on Domestic Economy, for the Use of Young Ladies at Home, and at School, 1848. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21829/21829-h/21829-h.htm#CHAPTER_XXIV.

Beecher, Catharine Esther, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The American Woman’s Home, Or, Principles of Domestic Science, 1869. https://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/cookbooks/americanwomanshome/amwh.html.

Blakemore, Erin. “Public Baths Were Meant to Uplift the Poor.” JSTOR Daily, September 9, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/public-baths-were-meant-to-uplift-the-poor/.

Dawson, Helen. “Deciphering the Elements: Cultural Meanings of Water in an Island Setting.” ResearchGate Accordia, no. 2014-2015 (2015): 13–26. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311534774_Deciphering_the_elements_Cultural_meanings_of_water_in_an_island_setting#pf6.

Graham, Jay P., Mitsuaki Hirai, and Seung-Sup Kim. “An Analysis of Water Collection Labor among Women and Children in 24 Sub-Saharan African Countries.” Edited by Virginia J Vitzthum. PLOS ONE 11, no. 6 (June 1, 2016): e0155981. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155981.

Hallett, Vicky. “Millions of Women Take a Long Walk with a 40-Pound Water Can.” Npr.org, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/07/07/484793736/millions-of-women-take-a-long-walk-with-a-40-pound-water-can.

Havlíček, Filip and Morcinek, Miroslav. “Waste and Pollution in the Ancient Roman Empire” Journal of Landscape Ecology 9, no.3 (2016): 33-49. https://doi.org/10.1515/jlecol-2016-0013

Medievalists.net. “Did People in the Middle Ages Take Baths?” Medievalists.net, November 28, 2023. https://www.medievalists.net/2023/11/people-middle-ages-baths/.

Prokter, Adrien. “Great Conduit.” Know Your London, November 12, 2014. https://knowyourlondon.wordpress.com/2014/11/12/great-conduit/.

The Friday Times. “Mohenjo-Daro’s 4,500-Year-Old Drainage System Still Functions: Archeology Dept.” The Friday Times, September 19, 2022. https://thefridaytimes.com/19-Sep-2022/mohenjo-daro-s-4-500-year-old-drainage-system-still-functions-archeology-dept.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Statistics and Facts.” US EPA, April 2, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/watersense/statistics-and-facts.

Valdez, Roger. “Could a Shelter Emergency Help Relax Expensive Building Codes.” Forbes, January 7, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rogervaldez/2025/01/07/could-a-shelter-emergency-help-relax-expensive-building-codes/.

[…] well-established tradition of drying food. Canning is water intensive, and not very accessible to women who live without running water in a land where water is precious. Government officials were not always sensitive to this […]

LikeLike

[…] improved the maternal fatality rate. One where women had access to some forms of birth control and water was routinely piped into your very own home, even if you weren’t […]

LikeLike