The current series is Inventions That Changed Women’s Lives, and today’s episode comes with a warning. This podcast is not intended to be explicit, not now, not ever. But a discussion of the invention of birth control does require mention of certain body parts and certain reproductive actions. If that’s going to bother you, maybe give this one a miss. Check out the 190 posts in the back catalog instead.

I left off last time with an aging Margaret Sanger, birth control advocate, looking at her life’s work and realizing that women’s ability to control their own reproduction really wasn’t that great. Condoms and withdrawal worked pretty well, but they required the cooperation of the man, and not every man was cooperative. Diaphragms, jellies, and douches were awkward to use, sometimes difficult to get, and not always effective anyway. Plus they were too expensive for a great many of the world’s women.

Sanger Meets Pincus

In the winter of 1950, Margaret Sanger, age 71, asked for a meeting with biologist Gregory Pincus. She had chosen him carefully because most respectable scientists weren’t going to agree to what she wanted.

Pincus was not particularly respectable. He had no prizes or inventions to his name. In the 1930s he had done in-vitro fertilization on rabbits. It was an amazing achievement, but the public had just read a hot-off-the-printing-press science fiction dystopia called Brave New World. Pincus had to explain to the public that he was not about to grow human test tube babies. Only a magazine article quoted him and accidentally left out the word “not”. The resulting uproar meant no tenure, eviction from Harvard, and no opportunities other than a small job in an underfunded, unknown private lab. Pincus never had enough money (Eig, 2; PBS; Asbell, 120-121)

That’s why he was willing to listen when the infamous Margaret Sanger said she wanted a new contraceptive. It had to be cheap and easy-to-use. A pill would be ideal. Something a woman could swallow and her partner didn’t even need to know about it because it wouldn’t interfere with the sexual act either before, during, or after. Also it had to be completely reversible when a woman was ready to have children. And above all, it needed to work. Reliably work. Also, Sanger wanted this pill fast. At 71, she didn’t need it personally, but bringing birth control to the world’s women was her life’s work, and she didn’t have time to waste.

And yes, she knew that laws against birth control existed practically everywhere, so no manufacturers were going to produce this, and no doctor would prescribe it. So how about it?

Pincus said: Yeah, that sounds doable.

That’s how the Pill began.

Research Begins

Sanger was reasonably well off, but she wasn’t fund-your-own-research-lab level of wealthy. However, she knew people who were. She scrounged up $2000 to get Pincus started. Even in the early 50’s that was pocket change for a job like this.

Pincus got started anyway. His idea was to use the hormone progesterone. He had already used it on rabbits, and he knew it prevented ovulation in rabbits.

In human women, progesterone is produced after an egg is fertilized. It changes the lining of the uterus so the egg can implant, and it shuts down the ovaries so no new eggs come out and get in the way. In other words, it’s a highly effective natural contraceptive. It’s why women can’t get pregnant when they are already pregnant.

On $2000, Pincus and his assistant began re-running their experiments on rabbits again, just to make sure. Then they did it on rats.

Meanwhile Sanger was scrounging for money. It eventually came via another woman who would never need the pill herself. Katharine Dexter McCormick was a wealthy, 75-year-old widow. She had known Sanger for years and had helped do all kinds of birth control work, including smuggling diaphragms in from Europe when it was still illegal to ship or import contraceptives.

McCormick had a personal reason for her interest in this subject. Her own marriage had seemed like a fairy tale at the time, but it ultimately meant decades of caring for a severely schizophrenic husband. She knew what it was to have a husband she couldn’t depend on, and a marriage in which the question of children was not as simple as the stereotypical family structure made it seem.

McCormick visited Pincus and made the first of many donations. She also became the de facto manager of the project. Like Sanger, she had no time to waste. She wanted the world’s women to have this pill, and she wanted them to have while she was still around to see it. In time, she would devote two million dollars to the development of the Pill, which was the lion’s share of the money. Unlike many drugs, the Pill was not developed by the R&D wing of a pharmaceutical company hoping to make a profit. It also wasn’t funded by the government. In fact, the government didn’t want to touch it with a ten-foot pole. President Eisenhower said that he could not “imagine anything more emphatically a subject that is not a proper political or governmental activity or function or responsibility … That’s not our business” (Asbell, 232). He later changed his mind, but at the time, his response was very typical.

The major power structures (whether they were governmental, medical, scientific, or religious) had no interest in developing an oral contraceptive. The Pill was developed because Margaret Sanger imagined it and Katherine McCormick paid for it. Neither woman was young enough to need the Pill personally. Neither of them planned to get rich because of it. They just thought it should exist. For the good of the world’s women.

Finding the Test Subjects

In the meantime, Pincus had done rabbits, he’d done rats. But at a certain point, you’ve gotta do actual human women. And he didn’t have any to experiment on.

To convince test subjects to participate, he needed a doctor to provide the necessary reassurances. There was also a little problem of the law. Pincus was working in Massachusetts, which had one of the most repressive birth control laws on the books. While it was not illegal to use a contraceptive, it was a felony to “exhibit, sell, prescribe, provide, or give out information” about them (Asbell, 160). Licensed doctors were allowed to prescribe for married persons, but Pincus wasn’t a doctor. That was certainly going to put a damper on further research.

The gynecologist Pincus found to fix all that was John Rock. In Rock’s practice, he often treated women who already had what Pincus was trying to achieve, and they weren’t happy about it. They were infertile and they wanted children. At first glance, they wouldn’t seem like good candidates to test a new contraceptive.

But Rock had a theory. His theory was that being pregnant helped your reproductive system mature and be more ready to get pregnant again later.

It was 1950 and you could still do medical experiments in a pretty haphazard way, so Rock told his “frustrated, but valiantly adventuresome” patients to take a progesterone and estrogen mix for a while. The idea was to trick their bodies into thinking they were already pregnant for a few months. Then when they went off these hormones, they’d experience “The Rock Rebound” and get pregnant more easily. In theory.

Really John Rock had no idea whether it would work or what the effects would be (Eig, 115 -117). But he was inadvertently running exactly the kind of trial Pincus wanted to do, only for completely opposite reasons. Pincus thought this was a golden opportunity.

Rock told Pincus that he had hit an unforeseen problem. Progesterone made his patients stop menstruating. It made some of them feel nauseated and some of their breasts grew larger. In other words, their bodies showed all the normal signs that indicate pregnancy. And these were women who wanted to be pregnant, so they were very excited because the treatment had already worked! Even before they got to the rebound part! Rock told them that wasn’t possible, but people believe what they want to believe until the evidence is inescapable. As of course it was, and then the women were crushed (Eig, 118).

It was Pincus who suggested that the solution was to have women stop taking progesterone five days a month. Then they would menstruate, and everyone would be clear that they were not pregnant (Eig, 118; Asbell, 128).

The alliance with John Rock also allowed Pincus to dodge the law. In Massachusetts, Pincus was not authorized to give anyone any form of contraception. As a doctor, John Rock technically could (Justia, Eisenstadt v. Baird), but if Pincus was working with Rock then the issue didn’t come up at all because this wasn’t contraceptive research. Goodness me, no. This was fertility research. No one objected to that.

The one person who did not think John Rock had anything to add to this project was Margaret Sanger. She objected to John Rock because he was a practicing Catholic. Decades of advocating for birth control had brought her into conflict with Catholic doctrine multiple times. She did not think a Catholic doctor could be trusted on this subject (Eig, 110; Asbell, 130). It was McCormick who talked her around and assured Sanger that Rock wasn’t going to sabotage the project.

Actually, it was to argue that Rock’s religion was an asset, not a liability. There were millions of Catholics and also a lot of non-Catholics who were worried about the moral and religious implications of birth control. A radical like Sanger was never going to convince them of anything. The mere fact that she was pushing it was a reason to reject it.

But when a believing Catholic like John Rock said that motherhood was important and valuable and good and that was precisely why it should be done with planning and forethought and intelligence? Well, this message hit differently than when people heard that it was about free love, sex with everyone, and pretending there are no consequences to that (Eig, 111). Messaging is important, and not everyone was hearing the same one. John Rock had the potential to be very reassuring to many people.

Finding Still More Test Subjects

Rock’s patients were great for showing that women could take these hormones without damaging their bodies, and also that some of them did get pregnant later. That part was very important, both because that was the actual goal for these particular women, and also because it proved the effects of the hormones were reversible.

But for the next trial, Pincus needed more women and for longer. These women had to agree to take an experimental drug daily, take their temperature daily, take a vaginal smear daily, do a urine test every 48 hours, plus an occasional biopsy (Eig, 130).

It was a fair bet that there weren’t going to be a lot of volunteers. McCormick was frustrated by how hard this was. In one letter to Sanger, she explained that “Human females are not as easy to investigate as rabbits in cages. The latter can be intensively controlled all the time, whereas the human females leave town at unexpected times and so cannot be examined at a certain period; they also forget to take the medicine sometimes.” Also, women often had to explain to their husbands why they were taking an experimental drug, and they complained about side effects a lot more than rabbits do (Eig, 157). What they needed Sanger and McCormick agreed ruefully was a “cage of ovulating females” (Asbell, 134).

Pincus and Rock did find some women to participate, but most of them dropped out and those who stayed had a 15 percent ovulation rate. He knew Sanger and McCormick would not consider that a reliable contraceptive (Eig, 134).

Ethically Dubious Studies

Eventually, the team found several places to test and all of them raise ethical eyebrows in the modern world.

One set of tests was done at a mental asylum with notoriously bad conditions. Pincus didn’t have to sign any permission forms. He just came in and said he’d like to perform some experiments and then he did (Eig, 177). Ultimately, this proved nothing. The women weren’t having sex, so it was difficult to be sure it was working. Pincus also gave the hormone to men. Just to see what it did, you know? Results were inconclusive (Eig, 180).

The more important studies were done in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico was attractive for several reasons:

- Birth control was legal and there were already birth control clinics across the island.

- They had trained doctors who could be trusted to run the studies.

- Flights from the US were quick and frequent.

- The US press might not notice if something went wrong.

See what I mean about raised eyebrows?

McCormick cast doubts on whether Puerto Rican women could be trusted to follow the regimen. There was a lot of class bias and maybe racial bias in this view, but she wasn’t alone (get reference). The bitter truth was few women of any class or race could be trusted to do this. Hadn’t the high dropout rate in Massachusetts already proved this to be a problem? McCormick wasn’t wrong to doubt that the regimen would be followed. She was just wrong to think being Puerto Rican had anything to do with that.

In 1954, the Puerto Rican trials began. And women dropped out, just like they had done in Massachusetts. This was because Pincus and Rock didn’t know how to find women who were truly motivated by the idea of birth control.

But Dr. Edris Rice-Wray did. She worked for the Department of Health in a poor district of San Juan. They had a new government funded housing development and a large population of young families who were very, very interested in not overcrowding their small apartments. Rice-Wray recruited women in numbers Pincus and Rock had not been able to achieve anywhere.

She began distributed the pills in April 1956. She tried to give clear instructions, but they weren’t always followed, not because the women were Puerto Rican but because they were human. One woman took all the pills at once. Others shared them with friends (Eig, 238). Many struggled to keep track of whether they had taken one that day or not. (Modern packaging can help with that, but that packaging hadn’t been invented yet, and the packaging of the pill is a whole story in and of itself.)

Also, some bad press scared some women off. These ranged from religious complaints to the belief that these white people from the US were trying to sterilize Puerto Ricans. Rice-Wray was forced to resign from her job (Eig, 239; Asbell, 146).

But with time the bad publicity actually drove women to the trials. Some women came asking to join. They had heard their local priest preach against it, and now that they knew it existed, they wanted some too (Eig, 240). These women’s life experiences varied considerably, but many were happy with the Pill because it was the first birth control they could take without their husband’s knowledge (Eig, 241).

The results were very promising, and Pincus was delighted. Rice-Wray was less delighted. Sure, it prevented pregnancy pretty well, but there were also complaints of nausea, headaches, and worse.

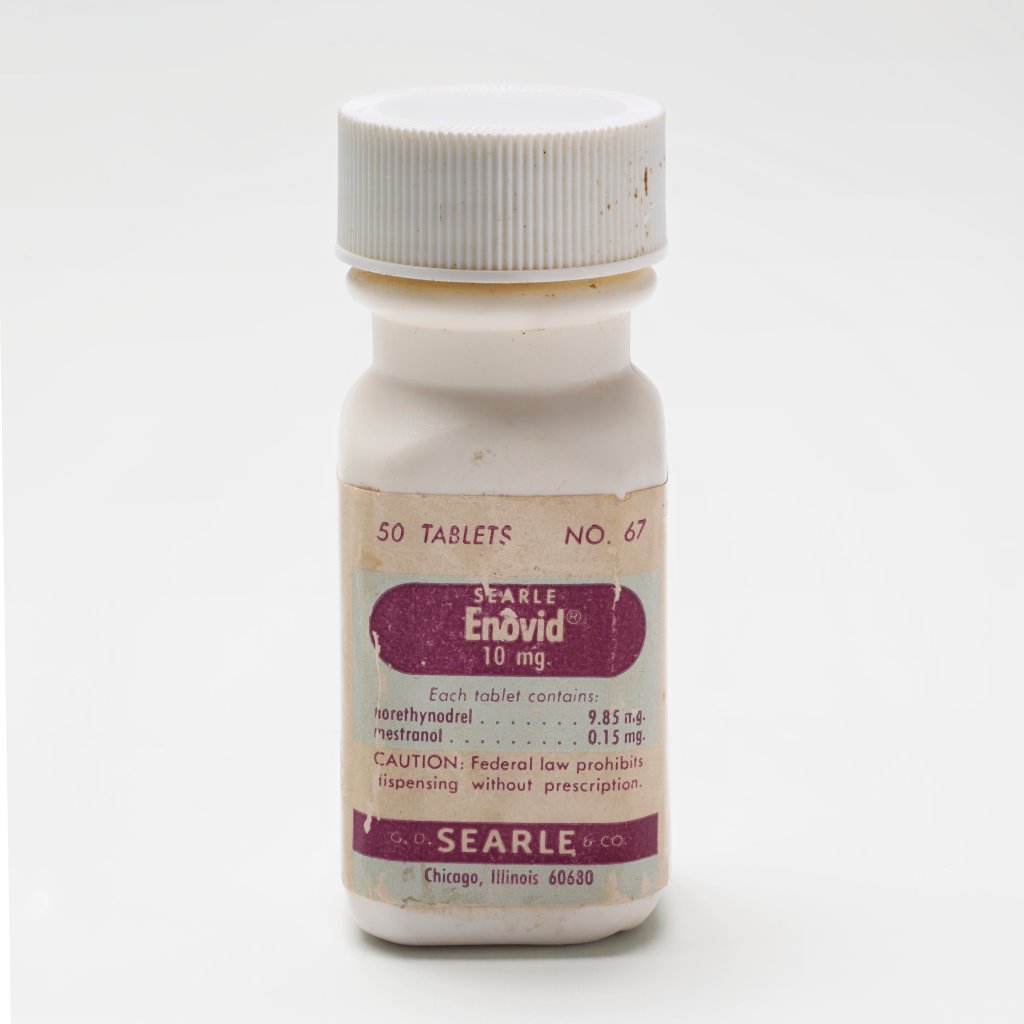

Pincus was in negotiations with the Searle drug company about producing and marketing this miracle pill. Rice-Wray was the only woman in the room at these meetings, and she said the side effects should be taken seriously (Eig, 243; Asbell, 147). I’m not sure how seriously the men took her. They certainly moved forward with the new drug they called Enovid. Pincus just called it the Pill. And that was a name that stuck.

More trials were ordered in Puerto Rico and in Haiti, which was Rice-Wray’s suggestion (Asbell, 151). Some of these trials violated medical ethics. Women weren’t necessarily told all of the things they should have been told (Eig, 252).

One batch of the pills got contaminated with synthetic estrogen. To everyone’s surprise, that brought the side effects down, and after that they purposely added the estrogen (Eig, 252; Asbell, 149).

Applying for FDA Approval

In 1957, it was time to apply for FDA approval. Even after all this work, the number of women who had been studied was not really that high (about 130). So Pincus did not count the number of women. He counted menstrual cycles studied instead. That made a much more impressive number (Eig, 253).

He also didn’t mention contraception. That would have opened a legal can of worms. Enovid wasn’t a contraceptive. It was for regulating menstrual problems. It was even for fertility because the Rock Rebound did seem to happen in a small number of cases.

The FDA wasn’t stupid, of course. They knew perfectly well what Pincus had been doing, and the purpose he had in mind. But officially, they were not approving this drug on its ability to prevent pregnancy. Only on its ability to regulate menstruation, and it was undeniably good at that. The drug passed. If doctors and patients used it for any off-label purposes, that wasn’t the FDA’s fault, was it?

With FDA approval in hand, Pincus felt free to tell everyone what a great contraceptive he had invented. Rock was nervous about this and asked Pincus to tone it down. Pincus didn’t.

The Searle company executives were delighted. They were flooded with requests for the drug. The returns were well beyond their wildest dreams, and best of all, they hadn’t even paid for the R&D because Katherine Dexter McCormick had done that (Eig, 264). It was practically all profit.

The tests went on, of course, because there was still the question of long-term effects. But now there was no trouble about finding enough women virtually anywhere. Women were motivated. It was amazing how many women suddenly had menstrual disorders that needed regulating. 500,000 women took the pill when that was still its official purpose (Eig, 281).

By 1958, Searle revised its application to the FDA for approval of Enovid as a contraceptive. The drug had not changed. Only its stated purpose had. This has been called going out on the “longest limb in pharmaceutical history” (Asbell, 164). Seventeen states still had laws on the books forbidding contraceptives (Eig, 276). But it was also clear that demand was enormous. The company that brought this to market was going to do very, very well. Unless they were totally ruined by a public or legal backlash. One of the two. Searle chose to go for it.

The FDA said yes on May 9, 1960. In 1965 the US Supreme Court ruled that birth control is private, protected, and legal.

Success (more or less)

For Margaret Sanger and Katharine McCormick this was the culmination of a lifetime of work. There had been plenty of reason to think they would not live to see it, but they did. Sanger was 80. McCormick was 84. She considered her 2 million dollars well spent when she went to a drugstore and quietly picked up a prescription for Enovid for a friend (Eig, 280.

In 1963, Margaret Sanger spoke to a journalist from her nursing home. “I knew I was right,” she said. “It was as simple as that. I knew I was right!” (Eig, 317). Sanger’s unshakeable conviction had brought birth control from seedy back alleys to the mainstream.

But there are plenty of points on which she was actually wrong. Sanger thought the Pill would lift women out of poverty worldwide. Actually, the Pill remains most popular in first world countries, and even there it is mostly used by the middle and upper classes. Poverty remains a big problem. Sanger thought the Pill would put a stop the world’s overpopulation and the overconsumption of resources. The global population is much bigger now than it was then. How big a problem that is and what to do about it remains a hotly debated topic (May, 54). Sanger thought birth control would make couples happier. It’s hard to measure happiness, but the divorce rate suggests that it’s perfectly possible to be miserable on the Pill (Eig, 318).

Many people thought that the existence of the Pill would mean far more promiscuous sex. Sanger was pretty okay with that goal, but there are still arguments about how much the Pill really changed things. Maybe it just made people more willing to admit to sex that had been going on all along.

What is pretty undeniable is that the Pill allowed women to plan in a way they never had been able to do before, regardless of whether they were planning for a career or for their health or for the health and wellbeing of children they already had.

A Pill for Men

Any or all of these points could be a podcast episode in and of themselves, but I am going to address the most common feminist critique of the Pill. This is the theory that the Pill has allowed men to not think about contraception at all. They have no responsibility, they don’t have to pay for it, they don’t have to visit a doctor to get it, they don’t have to remember to take it, and they don’t have to deal with any side effects (which do still exist for some women, even at the lower dosages that are prescribed nowadays). This is totally unfair. Where’s the Pill for men?

All of that is undeniably true, and I’ve heard a variety of answers, but since I’m a historian not a scientist, I would say the reason is the Pill is for women is that Sanger and McCormick were not interested in a pill for men. This is not actually a new argument; the subject that was discussed while the Pill was in development. For Sanger and McCormick the entire point was to put the responsibility on women because that meant that for the first time in history, women were in control. A woman could take it with or without her partner’s consent, and even without his knowledge if that was how it needed to be. It was her body that paid the price for pregnancy, so she should be the one to decide on birth control. A pill for men would not have accomplished their goals.

Whether or not you agree with their goals, it’s undeniable that for many women the Pill was revolutionary.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting the show on Patreon. There are options for every budget, including one-time purchase. There are also a variety of potential benefits, including that new bonus episode on packaging the pilll. No matter which method you choose, you are much appreciated for helping keep these regular episodes free and available to everyone.

Selected Sources

Angus Maclaren. A History of Contraception : From Antiquity to the Present Day. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1994. https://archive.org/details/historyofcontrac0000mcla/page/28/mode/2up?q=silphium.

Aristotle. Historia Animalium. Translated by David M Balme and Allan Gotthelf. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908. https://archive.org/details/historiaanimaliu00aris_0/page/n323/mode/2up?q=cedar.

Asbell, Bernard. The Pill : A Biography of the Drug That Changed the World. New York: Random House, 1995.

Brazan, Madison. “Controlling Their Bodies: Ancient Roman Women and Contraceptives,” n.d. https://provost.utsa.edu/undergraduate-research/journal/files/vol4/JURSW.Brazan.COLFA.revised.pdf.

Eig, Jonathan. The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014.

Justia. “Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).” Justia Law, 1972. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/405/438/.

Jütte. Robert. Contraception : A History. Cambridge, Uk ; Malden, Ma: Polity, 2008.

May, Elaine Tyler. America and the Pill : A History of Promise, Peril, and Liberation. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D29%3Achapter%3D27

Riddle, John M.. Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Sohn, Amy. “Charles Knowlton, the Father of American Birth Control.” JSTOR Daily, March 21, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/charles-knowlton-the-father-of-american-birth-control/.

Tone, Andrea. Devices and Desires : A History of Contraceptives in America. New York: Hill And Wang, A Division Of Farrar, Straus And Giroux, 2002.

uscode.house.gov. “Comstock Act (18 USC 1461: Mailing Obscene or Crime-Inciting Matter),” 1873. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title18-section1461&num=0&edition=prelim.

http://www.ucl.ac.uk. “Kahun Medical Papyrus.” Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/med/birthpapyrus.html.

[…] Mary lived to be 99, she even saw the release of the world’s first oral contraceptive. Given her age, it’s entirely possible she didn’t approve, but let’s not just […]

LikeLike