It was the summer of 1658 in the city of Rome. The French painter Simon Imbert sat down to his dinner as usual. There was a little lettuce, endive, and bread in meat broth, all provided by his pretty, young, Italian wife Anna Maria Conti.

A few hours later he began to vomit.

A couple of days later, a doctor visited and diagnosed him with inflammation of the liver. The prescribed remedies had no effect. Imbert continued to worsen, until he was writhing with fever, difficulty breathing, and overwhelming thirst.

In two weeks, he was dead.

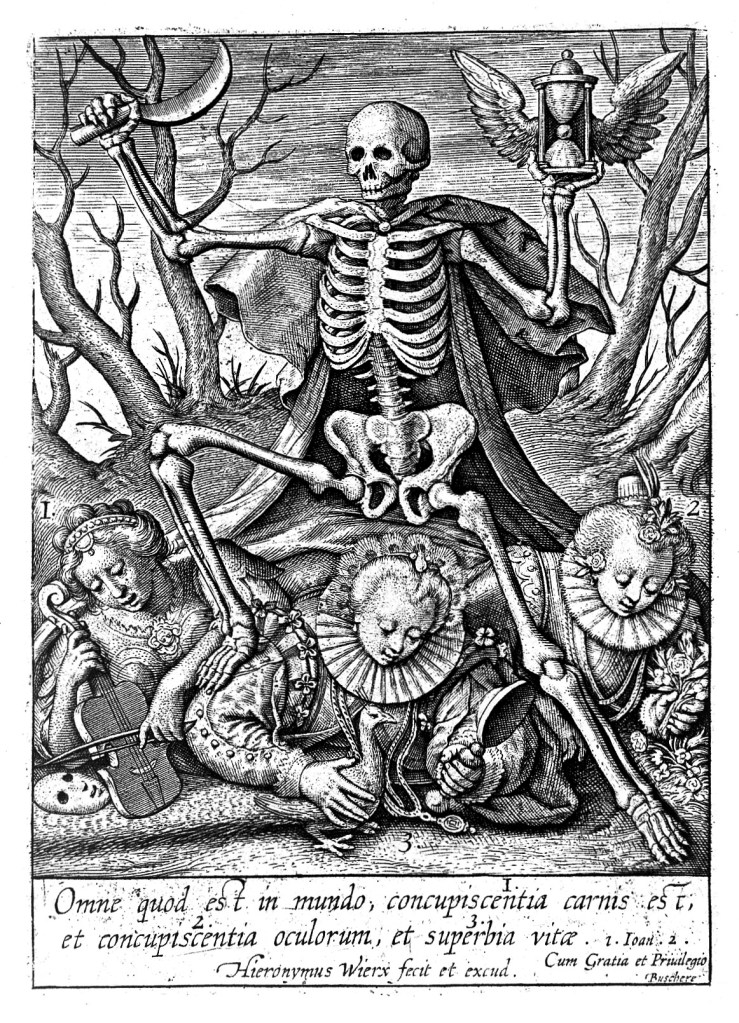

Willem van Nieulandt II (1584–1635) (Wikimedia Comons)

The world is full of many perils, and many illnesses that have exactly those symptoms. So there was no particular reason to suspect foul play.

But Anna Maria Conti’s name was mentioned many months later, the following year, in the course of a legal investigation run by Stefano Bracchi. Bracchi was following the trail of an alleged ring of poisoners. A ring of female poisoners.

It was an allegation guaranteed to chill the heart of any man who sat down to a regular meal prepared by his wife. And Simon Imbert was not the only man who was dead.

There was Andrea Borelli, the innkeeper. There was Giuseppe Cencietti, the barber. There was Giovanni Pietro Beltrammi, the wool dyer. There was Francesco Baldeschi, the gilder. There was Marc’Antonio Ranieri, of unknown profession. There was Antonio Romieri, the butcher, and Giuseppe Rosati, the cloth cutter. There was Antonio Contarini, the linener. And Francesco Ladi, the butler. Paolo Palazzi, a tailor, and Antonio Giuli, a debt-ridden mattress maker. Also Castore Sartorio, a cavalier, and Francesco Tamburini, a woodworker. There was even a duke dead: Francesco Maria Cesi, Duke of Ceri.

All of these names surfaced in the course of the Bracchi investigation. As did the names of these men’s wives, who were very much alive, and perhaps benefiting from their new-found freedom and status as widows.

The First Woman Caught

The Bracchi investigation did not begin with Anna Maria Conti. It began with Giovanna de Grandis, who was arrested in January of 1659, while in the very act of handing a client a vial of liquid, which she initially tried to say was just a face cleanser (Monson, 38).

Giovanna was an aging widow with few resources and much debt. She did not get any legal representation, whether at her own expense or at any other. There was just her, Stefano Bracchi, and the scribe who wrote it all down in a record that still exists in the archives in Rome. Bracchi led her to believe that he already knew everything, for her accomplices had told him. This was not true, but believing it was, Giovanna’s resolve cracked.

She told Bracchi that she knew how to brew a certain potion that was most definitely not a face cleanser. She had learned to do so from a woman named Giulia Siciliana, stepmother of her friend, Gironima Spana (Monson, 47). Gironima was arrested later that day. Giulia Siciliana was not, but only because she was already dead herself.

Giovanna’s testimony went on and on, over repeated interrogations. She seems to have realized that her life had almost—but not quite—hit rock bottom. She told Bracchi quite frankly that she no longer desired to live, but she would not want to be tortured.

Bracchi did not respond to this, and Giovanna may have assumed they had an agreement. She would tell all she knew, and he would not torture her. But if Bracchi ever actually said that, the scribe did not write it down.

Giovanna also implicated her friends Maria Spinola and Graziosa Farina, both of whom she said sold the poison to other women. Naturally, they were arrested as well. Between them, they gave Bracchi the names of many of the widows of the dead men I listed earlier. It was Maria Spinola who provided Anna Maria Conti’s name (Monson, 112).

Over time, Bracchi was pulling together the story of a network of women who dealt in dark things, brewing poisonous waters in secret places, and selling them throughout Rome to wives who used them to kill their unsuspecting husbands.

The Deadly Recipe

Giovanna also provided the exact recipe for this deadly potion. It was two ounces of arsenic and one grosso of lead bird shot all ground up together. Then mix it with a foglietta-and-a-half of water, seal in a new jar, and put the jar in the fire to boil until the water drops an inch. It is then colorless, odorless, and tasteless, but 5 to 6 drops will make you ill, and administered repeatedly over a week or so, it will make you dead (Monson, 96).

The arsenic was the key ingredient, of course, and it was not particularly difficult to obtain. It was used in beauty products and in medicines. Anyone might have learned and duplicated this technique. From Bracchi’s point of view, it was a matter of utmost importance to collect anyone who knew the secret recipe.

His investigation went on, arresting and interrogating more and more women, either for having sold the poison or for having used it. But to achieve a hanging, the law required a confession (Monson, 164), and many of the interrogated women strenuously denied having done anything of the kind. They often denied knowing each other.

The Tortured Confessions

Giovanna was tortured, as any defense lawyer could have told her she would be. On May 19th, Bracchi subjected her to the sibila, which meant wrapping cords around her fingers and drawing them tighter and tighter for up to fifteen minutes. This was considered a “gentle” form of torture, as compared with the strappado, which meant tying your wrists behind your back and hanging you by them.

Either way, the theory was that the guilty would confess under torture, and the innocent would not. Which is a ridiculous theory, but it was widely accepted at this time.

Giovanna had already confessed, but the other standard use of torture was to prove the accuser. The theory was that an honest accuser tortured in front of the accused would not retract their accusation. And that I can believe. Why on earth would they retract under those circumstances? All that would do would prove them to have lied in the first place, which would not necessarily end the torture any faster, and it might lead to more difficulties later.

Giovanna screamed and cried while three of the women she claimed to have sold poison to were forced to watch. Giovanna insisted her testimony was true. The three women naturally insisted it was not (Monson, 91). Giovanna suffered the sibila again two days later in front of Gironima Spana, who still denied having anything to do with poison of any kind.

Any confession or accusation made under torture is suspect in my mind, so I don’t think Giovanna’s testimony proves much either way. But Anna Maria Conti’s testimony is not so easy to dismiss. Socially, she was a cut above most of the accused. She was not aristocratic, but she had enough money to have servants and a carriage. She had friends who might have made a fuss if she had been mistreated by the law. And most crucially, she had papal immunity. That is to say, someone (presumably one of these influential friends) had arranged it with the pope himself that if she gave a full confession of everything she knew, she would not be prosecuted or punished, no matter what she said.

This meant Anna Maria Conti was very lucky, compared with her fellow accused. Bracchi did not arrest her or summon her to a grim prison to interrogate her. He did her the honor of coming to her home for the interview. And the tale she told is bone-chilling in quite a different way, though it’s not at all clear whether Bracchi recognized that.

Anna Maria Conti’s Tale

Anna Maria said that her father arranged a marriage for her when she was still in her teens, and she bore a son. Her husband was more than twice her age, and he died, leaving her a widow while she was still in her teens. Her father quickly found another husband for her, one Simon Imbert, a Frenchman, who was also very much older than her.

It soon became clear that Imbert had married her for her father’s property. He told Anna Maria to convince her father to transfer control of the property to him. If she did not, he would kill her, and her son and her father too. Her father did die on December 11, 1657, after two weeks of fever and intense thirst.

Though the property was now in Imbert’s control, his intimidation did not end. He threatened Anna Maria with a knife. He began strangling her and went far enough to leave bruises, though authorities arrived in time to prevent her death. He told her that he had poisoned her father, and someday he would do the same to her. He also repeatedly punched her the stomach, even though he knew full well that she was pregnant with his child.

A battered wife had few options in 17th century Italy. Divorce was not acceptable. Even separation was difficult and generally meant a total lack of financial support. Being socially well connected did Anna Maria no good whatsoever. Wife beating was accepted as a reality in all social classes. Murder was a crime, but presumably, Imbert would have denied killing her father if she had reported him to the law.

Desperately, Anna Maria looked for help in the only place she had any hope of finding it: from other women. Specifically, she wanted a wise woman, the kind who could brew something that could, by her own account, reconcile husbands and wives.

Yes, that’s right, Anna Maria said she was looking for a potion that would act as a sort of love potion. Not to catch her man in the first place, but to make him treat her more kindly and cherish her. It was a matter of life and death.

Anna Maria sent her servant Benedetta to a woman named Laura Crispoldi. Laura returned a message that if Anna Maria wanted a reconciliation, that could be done. But if Anna Maria wanted to be entirely free of her husband, that could be done as well. And no divorce would be necessary.

Anna Maria considered her position. She considered that her husband had said himself that he murdered her father, that he might well murder her and the two children she was responsible for. She decided that her husband was the one who deserved to die. She accepted Laura’s second suggestion and asked for the poisonous potion.

The price was fifty scudi, which Anna Maria did not have. But she paid what she could, promised the rest, and received the little vial of what looked like water, but wasn’t. She also received the instructions: if you want to kill him quickly, give him a little bit every day. If you’d like to prolong it, every other day. Anna Maria chose every day, and yes, she poured the drops of poison onto the bread in Imbert’s evening meat broth. In two weeks, he was dead

But his death wasn’t the end of her troubles, for Laura Crispoldi turned out to be a hard creditor, always hounding her for more money. She was still doing so at the time of Anna Maria’s testimony.

The Expanding Investigation

Stefano Bracchi took this statement, and there’s no knowing what he thought of it. Technically, Anna Maria was a self-confessed murderer. But the modern mind can find a great deal of sympathy for her choices. Whether Bracchi’s mind could find any sympathy is anyone’s guess. Anna Maria had her papal immunity, so there was nothing more to be done. She was never arrested or imprisoned.

Her servant Benedetta was not so lucky. For her role as an accessory to murder, she was arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and eventually flogged through the streets and banished, which was hardly fair (Monson,192).

Laura Crispoldi was in trouble too. Because of course Bracchi tracked her down. In point of fact, he was far more interested in the sellers of the poison, than he was in the users of the poison. You could argue that this was simply good practice: cut the problem off at its source. Anna Maria would not have known how to dispose of her husband (might never even have thought of doing it) had Laura not suggested it and sold her the vial.

But it is also possible that Bracchi did think there was some justice in Anna Maria’s actions, papal immunity aside. Not for the wife beating. That was just status quo. But poisoning the father-in-law was bad. And there was another point in Anna Maria’s testimony: punching her in the stomach while knowing she was pregnant. Abortion was a very serious sin, specifically discussed in the papal bull of 1588. Only the pope could absolve you of a sin so heinous, and interestingly, that papal bull did not emphasize women as sinners in this respect so much as men. Specifically, men who caused the violent and untimely death of their own offspring, by whatever means, including beating a woman around the stomach while she was pregnant (Monson, 116). This is probably why both Anna Maria and Benedetta made such a point of mentioning that part. It was an attempt to justify themselves.

Still you couldn’t have women taking justice into their own hands, could you? And none of this excused Laura Crispoldi.

Laura was not given the honor of an interrogation in the comfort of her own home. She was hauled in for questioning, where she denied everything.

The trouble was she was identified by Benedetta, who had not yet been banished. Benedetta was subjected to the sibila, but she stuck to her story. Then Giovanna de Grandis was brought in, and she also identified Laura as one of her confederates.

In the end, Laura confessed to selling the poison, just like Giovanna de Grandis, Maria Spinola, and Graziosa Farina.

Gironima Spana did not confess, and after five months in prison and many interrogations, she was screaming insults at the court and insisting they could not hang her. She had given them no confession, and no evidence of a crime had been found at her house. She was legally right, but when it became clear that they intended to hang her anyway, the spirit went out of her. In the end, she confessed as well (Monson, 165).

The Wheels of Justice

On Saturday, July 5, 1659, these five women, who had all confessed before the law to selling a deadly poison, were given the chance to make their final confessions before God. They received their final sacraments, and they made provisions for their property. For the most part, they didn’t have much. If they were truly guilty, there was a reason they had resorted to selling poisons, and in my view, it wasn’t wickedness or temptations of the devil. It was poverty. Especially for Laura Crispoldi, who said she had to hound Anna Maria Conti for more money, because thieves had taken the entirety of what Anna Maria initially paid.

The nooses were draped around their necks, and they were loaded in carts and driven through all the major streets of Rome before they arrived at the gallows in the Campo de Fiori. And there they were hanged, one by one, before a crowd of onlookers (Monson, 164-169).

The following day, a printed broadside circulated through the city making it clear that selling any kind of poison was illegal without a license, regardless of its intended use. The broadside also outlined the usual symptoms of the poisoned victims and recommended an antidote: three ounces of lemon juice or vinegar, ingested while giving thanks to God. I have no comment on the giving thanks to God part, but I did look up modern antidotes to arsenic poisoning (CDC). Neither lemon juice nor vinegar got a mention at all.

The Legend

The sensationalizing of this tale began almost immediately. The news report said the network of poisoners had extended all throughout Rome, and a local ambassador suggested that as many as five hundred husbands had been killed (Monson, 1). But if even a fraction of that number had actually been killed, then Bracchi’s investigation missed an enormous amount.

The tellings and retellings eventually focused on Gironima Spana as the mastermind of this crime syndicate at the time of its demise. She was said to have learned her trade from her Sicilian stepmother Giulia Tofana, who learned the deadly recipe from her own mother Thofania d’Adamo. If any of that is true, then you have to credit the sensationalized retellings as getting things more accurately than Bracchi’s official reports, which do not say that.

Nevertheless, legend has made Giulia Tofana the true black widow, the one who died of natural causes without ever being found out in her wicked web of murder. Her name was also attached to the poison itself, which came to be known as Aqua Tofana. The Bracchi reports never use that name.

Aqua Tofana became the secret fear of men for generations. Most famously, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worried that he had been given Aqua Tofana during his final illness. It is generally believed that Mozart was more paranoid than accurate, but he was not alone. For men who were suffering, it was sometimes a comfort to have a woman to blame, rather than the mysterious failings of their own mortal body.

But that comfort came at a price, and the price was fear. Crime novels were not yet a thing, but even then it was more or less known that a murderer needs means, opportunity, and motive to commit the deed. Aqua Tofana was the means. Surely no one has as much opportunity to poison you as your own spouse. And certainly many of these men were fully aware that they had given their wives more than enough motive. That’s what happens when you mistreat your family, and your death is their only possible escape. Anna Maria’s tale told of physical and emotional abuse, the murder of her father, and the attempted abortion of her child. The other widows in this story had sadly similar tales, sometimes with the addition that the husband forced his wife into prostitution, or into “unnatural” acts with him, or to watch while he performed such acts with others, including young boys.

If I’m allowed to draw a moral out of this story, I’d say: be kind to the people around you. Even if for no other reason than that they’re less likely to poison you that way.

In fact, this story has only one murderous motivation for which I can find little sympathy. The Duchess of Ceri was said to have poisoned her husband because she was infatuated with another man. Most uncharacteristically, Stefano Bracchi ignored this entirely. Clearly, he had no desire to chase down a member of the aristocracy. The Duchess of Ceri was never arrested or questioned in any way. So if she had another motive, she never had to explain it. If she did poison the Duke because she was infatuated with another man, the Duke got no justice from any earthly court.

On the other hand, given the nature of most of these confessions, it’s possible to dismiss almost all of them. Perhaps the Duke and many of the other husbands died of purely natural causes. Or perhaps they did not, but the women exaggerated the husbands’ offenses to justify their crimes. I led with Anna Maria Conti’s story because she was under no duress when she confessed herself a murderer. She could have said she thought the vial of liquid would be the reconciliation potion she originally asked for, or that it was an accident, or that someone else had poisoned Simon Imbert. But she freely admitted to the crime. That seems to me to be the most credible account in the whole tangled story.

But there is one point that suggests that some of the other accusations had an element of truth as well. Gironima Spana insisted that no evidence of crime had been found in her house. But after her death, in the spring of 1660, the new owner of the her house hired a man to prepare the garden for a new season. The gardener’s digging turned up a vial of clear liquid, and the owner, knowing whose house he lived in, turned it over to the legal authorities (Monson, 188).

Stefano Bracchi had closed his investigation. He had no more witnesses, and no one was still incarcerated. Nevertheless, for completeness’ sake, he tested this mysterious liquid by feeding it to a dog.

The dog died.

Today I have special thanks to Maria who made a one-time donation. If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting the show on Patreon or on Buy Me a Coffee. There are options for every budget, including one-time purchase. No matter which method you choose, you are much appreciated for helping keep these regular episodes free and available to everyone.

Selected Sources

My major source today is Craig Monson’s The Black Widows of the Eternal City. Most unusually for me, it is also pretty much my only source, which I always find a little worrisome. An enormous amount has been written about Aqua Tofana but as far as I can tell, Monson is the only one who troubled to read the 17th century court record, rather than the 19th century fictionalized accounts. I hope his interpretation is accurate because I certainly can’t read handwritten 17th century Italian and it isn’t online anyway.

The music in the audio version of this post is from from The Four Seasons by Antonio Vivaldi, recorded by The Wichita State University Chamber Players with John Harrison on Violin and Robert Turizziani and as Conductor. The recording is licensed under the Creative Commons and available under the classicals.de website.

CDC. “Arsenic Toxicity: How Should Patients Overexposed to Arsenic Be Treated and Managed? | Environmental Medicine | ATSDR.” Cdc.gov, May 25, 2023. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_atsdr_cdc_gov/csem/arsenic/patient_exposed.html.

Monson, Craig. The Black Widows of the Eternal City : The True Story of Rome’s Most Infamous Poisoners. Ann Arbor University Of Michigan Press, 2020.

[…] which of the inventions I covered that did have female inventors: the disposable diaper and a poison to kill husbands. For obvious reasons, there weren’t a lot of male competitors to edge women out of those […]

LikeLike