Both baby boys and baby girls eliminate bodily waste, but there has often been serious gender inequity involved in the delicate question of who deals with the outflow. A British study in 1982 showed that a whopping 43% of fathers had never done diaper duty (University of Warwick). Not even once.

This is stunning when you realize that an average baby may use up to 3,000 diapers in the first year alone (Babylist). That’s 3,000 times that mom changed the diaper! Or perhaps a childcare worker changed it, but let’s face it, that childcare worker has a high probability of being female.

It was not always like this, though I’m not saying the fathers farther back did diaper duty more. Just that having diapers at all is a relatively recent phenomenon. The paper and plastic products we now use for diapers didn’t even exist for most of human history. As I discussed in episode 15.4 on spinning, cloth was unbelievably expensive for most of human history. So the solution to a baby’s sanitary needs was often something else, and what that solution was varied widely based on time and place.

Babies Without Diapers

In warm climates, it was (and sometimes still is) common to let very young children simply go naked. That doesn’t exactly solve the issue, as you’ve still got stuff to clean up, but the stuff doesn’t adhere to their skin and cause rashes, and it doesn’t require changing their clothes all the time. Your clothes, maybe, but not theirs.

Even your clothes can be saved if you use a system called elimination communication. This is still widely practiced in Asia, and it is basically potty training starting very early on, even within the first few weeks. The difference between it and Western potty training is that you aren’t so much training the child as training the caregiver. You can learn to recognize and encourage sounds and facial expressions that mean elimination is about to happen. Then you can quickly whisk your baby over the toilet, outside, or at least away from your own body in time (Go Diaper Free). Westerners like me are sometimes skeptical that this works, but I can assure you that millions of mothers are doing it every day. While I don’t have any idea how old the practice is, I think it’s a fair bet it’s been going on for millennia. It’s just not the kind of thing that gets written down in historical records.

Neither is any other option, to be honest. The other options we know about are mostly a matter of archaeology, rather than history. It’s also not surprising that many of them come from colder climates, where leaving the baby naked was not an option.

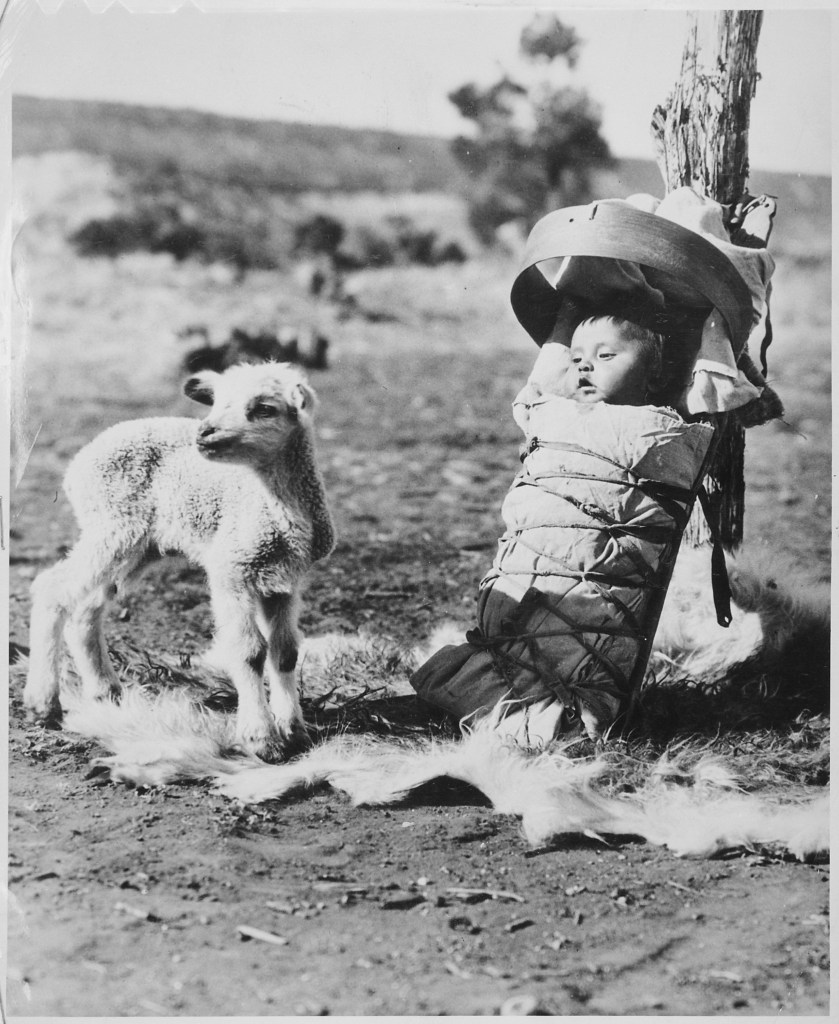

So we have, for example, a seal skin diaper from Point Barrow, Alaska, dating to about 900 CE. We have evidence that Chukchi babies in Siberia were dressed warmly, but with a bag between their legs. The bag was filled with dried moss, which could be replaced as necessary. Cradleboards are used in many cultures across the world, and they sometimes have a compartment or tube built in to catch any emerging organic matter (Tokat, 854-855, Krafchik, 4-5).

This is all well and good, but obviously someone’s going to have to replace that moss, clean that tube, or wash that seal skin fairly frequently, right? And like I say, there’s no direct historical evidence, but I think I won’t be alone in assuming that it was more likely to be mom than dad.

Another possibility is to use the blankets themselves. Nowadays, young babies might be swaddled, but the purpose is to keep them warm, keep them happy, and most importantly, keep them asleep. Modern swaddling is generally done in addition to a diaper, not instead of a diaper. But the swaddling blanket itself can do double duty, and that is the other commonly used method for millennia.

Of course, if you use something so large and multi-purpose for handling the bodily waste, then it will have to be washed very frequently, right? And I’ve discussed before just how big a job laundry was (episode 7.1). I am presuming that’s why I have multiple sources who assure me that in the past, swaddled babies were only changed every few days (Tokat, 854; Krafchik, 4). I am not at all sure how they know that. Both the ancient Greek doctor Soranus and the 17th century midwife Jane Sharp wrote books that include instructions on swaddling, but I read them, and they do not include one word about how often to unwrap that baby for a good scrub down (Soranus 83-85, Sharp). https://archive.org/details/soranusgynecolog0000unse/page/84/mode/2up?q=salt

Soranus does say to salt the baby first, which I suppose may have acted as a drying agent. I think it is safe to say, though, that a lot of babies had a lot of diaper rash.

A Diaper by Any Other Name

When cotton cloth got cheaper in the 18th century, mothers had a whole lot more of it at their disposal, and diapers became far more common. Mothers and house servants made these themselves, generally out of whatever cloth was ready to hand, but naturally the more absorbent the better, which is how we get into a question of etymology and linguistics.

Traditionally speaking, the word “diaper” has nothing to do with babies or bodily fluids of any kind. It’s a description of a type of woven cloth with small geometrical patterns like diamond shapes. Diaper, in this sense, could be used for many applications, including tablecloths and clothing. Diapered linen or cotton was absorbent, so it was a good choice for a baby’s bottom too. The diaper pattern of repeating diamonds might also be duplicated by cutting multiple diamonds of the fabric for extra layers too, which also added to the absorbency. Therefore, the word diaper began to take on its current American meaning.

It was called that in the UK too. The Brits didn’t switch to calling it a nappy until the 20th century. Nappy is short for napkin. Or maybe for the nap of the cloth, meaning the raised, textured, fuzzy bit. I’ve seen both etymologies claimed.

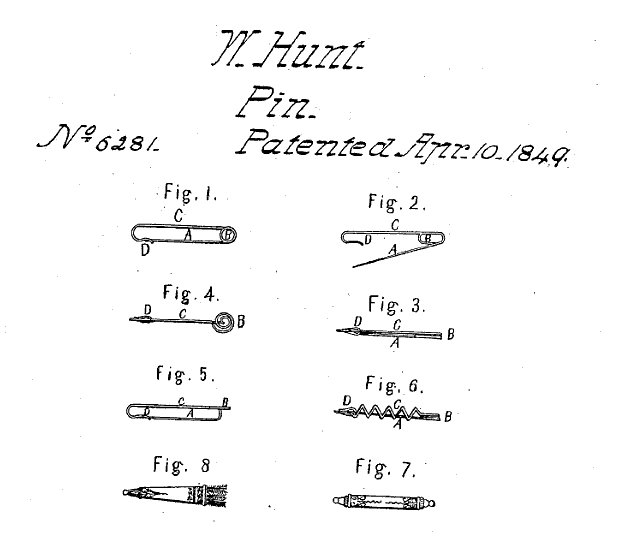

But no matter what you called it, it was the same messy thing and getting it to stay on and not leak was a constant battle. Tying it was probably the most common because it’s cheap. They did have straight pins, but of course those ran the risk of stabbing the baby if the baby moved. Fibula pins existed since the early Bronze Age, and were very popular in ancient Rome, but Roman babies were swaddled, not diapered, so they didn’t need them to hold those diapers on. The modern safety pin was not invented until 1849, and they most definitely were used on diapers, among other things. It made for a much snugger fit than previously possible.

But it all still had to be washed by hand. And diaper rash was definitely an issue. As I said before, it seems to me that diaper rash cannot have been anything new, but the late 19th century is when the sources start to mention it as if it’s suddenly a new thing. My guess is it’s the records that have changed, not the rash.

Constant Laundry

As late as 1927, the Butterick sewing company listed the contents of a layette, which means the collection of supplies a new mother needed. They layette included an absolute minimum of 24 diapers, by which they meant 18 by 18 squares of white absorbent fabric. The Butterick author cautions that this is only enough if you can have “constant laundry work done” (The Art of Dressmaking, 229).

Constant laundry sounds like a nightmare to me, but letting these things sit around waiting for the weekly wash doesn’t sound that appealing either. The truth was that someone had to deal with the laundry, but it was less likely to be the exhausted mother than you might think. Certainly some mothers had no other resources, but even middle-class women either had a servant or hired out the laundry. This is not because they had a lot of money to spare, but because labor was cheaper than it is now and doing the laundry was a whole lot harder. It was worth paying for.

Then there was the issue of clothes. As I said, there was a lot to be said for no clothes at all, and to this day a lot of those children doing elimination communication wear split crotch pants, which mean nothing needs to be removed in a hurry.

But the more common option in the West was dresses for all babies, regardless of gender. That 1927 Butterick layette list is the same for both baby boys and baby girls. It’s just one layette regardless, and it includes three dresses, three nightgowns, three petticoats, three kimonos. The purpose being that pants are a pain when you need to change the baby. Dresses work much better. Little boys didn’t graduate into a bifurcated garment until they were old enough to handle these issues on their own. Little girls, of course, never graduated into a bifurcated garment.

If all of this sounds like an awful lot of work, that’s because it was an awful lot of work. As the 20th century progressed, labor got a whole lot more expensive. There were a variety of reasons for that, but certainly a major one was that other job opportunities were opened up to women. A young woman who might once have taken in laundry to earn her bread was now finding that she could make more in a factory or an office. A good laundress was hard to find. More and more mothers had to manage these things on their own. Washing machines became more common, and commercial laundries were available to some women, but it was still a smelly, unpleasant business.

A Technical Solution

Many inventors had realized that diapers were an area of life that could use improvement, but none of the inventions described in the archives of any country’s patent office ever actually got to the point of changing women’s lives until well into the 20th century.

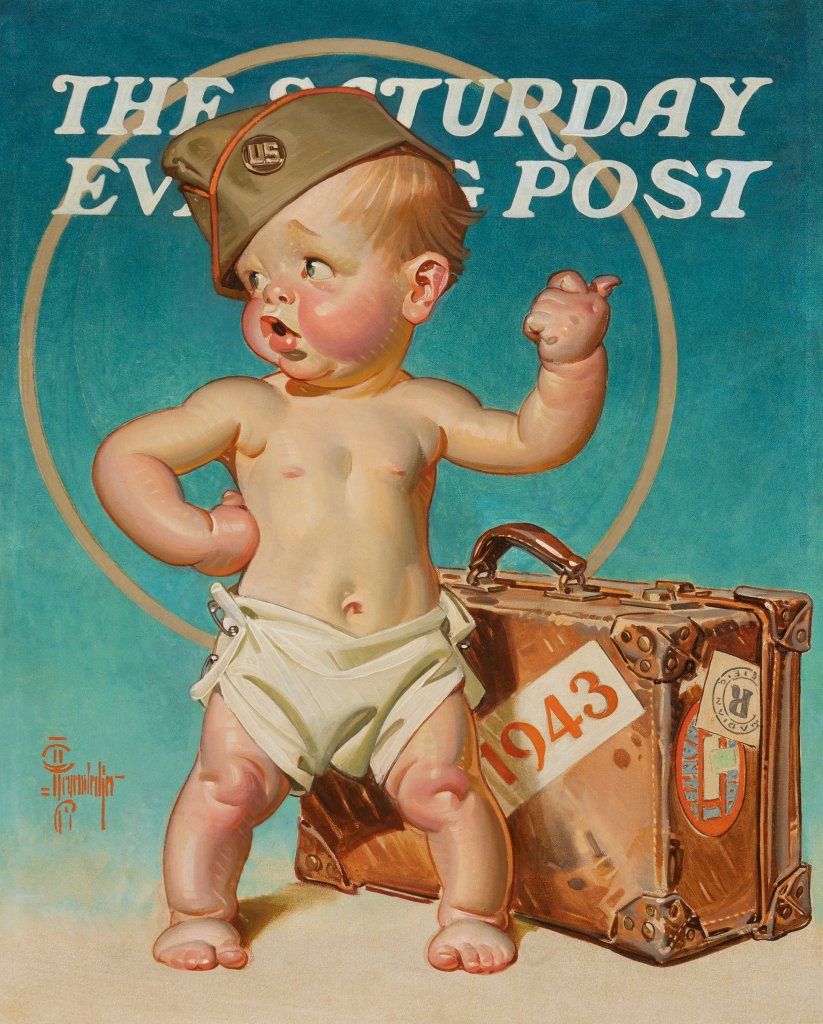

In the 1940s, a lot of young mothers entered the workforce because the men were away at war. This was progress in many ways, but there’s no denying that it made diaper duty still more difficult. Some unnamed entrepreneurs realized that and began opening commercial laundries that specialized in diapers and diapers only. Mothers who signed up for this service could designate a special, enclosed bin for the dirty diapers. Once a week the diaper service would show up to take that bin away to run it through eleven wash cycles with detergent and four more with boiling water alone (Tokat, 855). (You can see why many a mother thought this was worth paying for. Fifteen cycles in your home washing machine?!? Assuming you even have a home washing machine?!? The mind boggles. This truly is “constant laundry work.”)

But by the 1940s, changes were in the air, and they had already landed for some mothers. Starting in 1936, Swedish mothers had the option of buying help from the paper company Pauliström Bruk. Pauliström was using a new technique which turned wood pulp into super soft cellulose tissue. A few hospitals picked it up to cut, fold, and insert into infant diapers. When cleaning became necessary, they tossed the paper insert which caught most of the mess, so cleaning the actual diaper was much easier. Brand new mothers saw this in the hospital and then asked where they could buy the product for home use. Between 1936 and 1945, Pauliström did a booming business of 70 million diaper inserts. Eventually they also began selling a full diaper, but the diaper itself was reusable. Only the insert was intended to be disposed (Dyer, 6).

Super soft wood pulp was a case of invention preceding the actual usage. The scientists who developed it had not been thinking about the plight of young mothers at all.

The British and American Inventors

But young mothers were thinking about it. In 1947, British housewife Valerie Hunter Gordon was very, very tired of washing nappies. I do not think she had access to Pauliström’s inserts because she said in a later interview that she looked everywhere for disposable nappies, assuming that they must exist, right? But they didn’t. So she sat down at her sewing machine and made some out of old nylon parachutes left over from the war, tissue wadding, and cotton wool.

All of her friends wanted them too, and she ended up making over 600 by hand before applying for a patent in 1948 and licensing them to a manufacturing company in 1949 (BBC news). They saw some success in the British market, but they eventually met some stiff competition from across the pond.

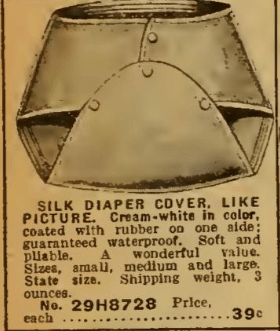

American housewife Marion Donovan was sick of washing the crib sheets. In her opinion, cotton cloth diapers acted “more as a wick than a sponge.” She pulled down her shower curtain, cut it up, and sewed it back together as a waterproof diaper cover with snaps, instead of safety pins. She eventually settled on parachute cloth, just as Valerie Hunter Gordon had, with a disposable insert for an absorbent diaper panel.

She took it around to all the big American manufacturers she could think of, and they universally told her they didn’t want. No woman wanted that. American mothers were happy with what they already had.

Now I don’t have any information on the gender of these uninterested executives, but I think we can safely guess that they were predominantly male, and even if there was an odd woman among them, she was obviously at work at the office, not at home changing diapers. This allowed them to completely overlook the fact that Marion Donovan was herself a representative of the very demographic she was trying to serve. Proof positive that at least one American mother was not happy with what she already had.

In 1949, Marion went into business for herself and sold her invention as a smash hit on Fifth Avenue (of all places) and two years later sold her company for two million dollars (Matchar).

These various options from various makers meant that many European and North American mothers in the 50s and 60s did have disposable diapers of one kind or another. But most of them were not using disposables exclusively because they cost too much. A typical price was 10 cents per diaper, which might not sound like much, but 10 cents was worth more then, and also babies go through a lot of diapers. It adds up. In contrast, a cloth diaper cost only 1-2 cents per diaper when you bought it, and then you reused it over and over. Even if you paid for a diaper cleaning service, that was about 3-5 cents per diaper, and of course it was cheaper if you washed them yourself (Dyer, 7). Many mothers did buy disposables, but they used them only when they were out of the house with their babies or maybe for overnight. At all other times, they stuck with cloth.

The Market Takeover

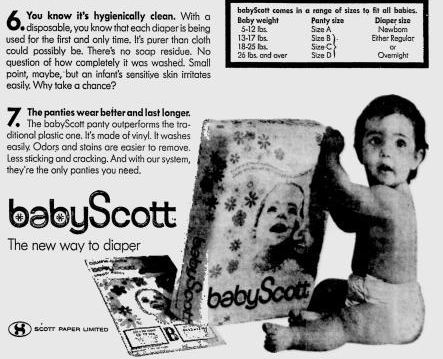

Clearly there was a market for a disposable, at least in Sweden, the UK, and the US, so it was only a matter of time before a real powerhouse company took notice and created their own version. The powerhouse company that got it to market was Proctor and Gamble. In 1961, the first Pampers hit the store shelves, and they pretty much eliminated the smaller players, so it’s a good thing Marion Donovan had already sold her company.

Pampers was not a reusable pant with a disposable insert, like all the previous versions. It was a one-piece disposable diaper. In 1961, Pampers sold at 6 cents per diaper, which was still more than a cotton diaper you washed yourself. But it wasn’t that much more than some of those diaper cleaning services, and it was a lot more convenient. The mothers who used diaper cleaning services were the affluent mothers, and those were the ones Proctor and Gamble expected to buy their disposables. But they were surprised when it turned out to be hugely popular with customers of many income levels. One mother in a poor area of New York City called them to say how grateful she was for Pampers. Six cents a diaper was a lot for her to pay, but it was worth it to avoid carrying dirty diapers down four flights of stairs and two blocks through a dangerous neighborhood to get to the laundromat (Dyer, 10). In many ways, poor mothers were the ones most in need of a disposable.

Other manufacturers quickly jumped on the one-piece disposable diaper bandwagon. A flurry of patents and improvements made them better and better, with more absorbent materials, thinner materials, cheaper materials, breathable materials, different sizes for different ages, elastic leg openings, better adhesives, pull up versions, etc (Dyer, 13; Krafchik, 5).

Between the mid-60s and the late 80s, disposable diapers virtually eliminated cotton diapers in one country after another across Europe and North America, and they made serious inroads in South America and Asia as well. In terms of new tech and product substitution, there are very few parallels in business history with how complete the market dominance was. It was a case where the new product was so clearly superior to the old product that consumers en masse decided there was no reason to hold on to the old one (Dyer, 9).

For mothers, this change was seismic, and most especially for those who were not affluent. Affluent mothers had always hired someone else to do the nastiest bits of motherhood, and surely diaper changes are number one in that category. For the women hired and the mothers who could not afford to hire, this nastiest job became so much easier. Which doesn’t mean we don’t complain about it, even as we toss most of the nastiness into a bin, without even thinking about laundry.

It’s better for the babies too. The new materials and the comparative frequency of changes mean less diaper rash.

Second Thoughts

But somewhere along the way, people did start to think about the effect of all those diapers in the landfill. And it’s not such good news. If the average baby goes through 3000 diapers in the first year, and most babies are in diapers for much longer than one year, and there were 132 million new babies in the year 2024 globally (United Nations, 8)… Well, let’s just say that’s an awful lot of disposable diapers. The Environmental Protection Agency says diapers are the third most common item in landfills, and they take 500 years to biodegrade (Tokat, 856).

The environmental concerns have led some consumers to decide that after all, yes, there was a reason to hold on to the old system. Reusable cloth diapers have had a resurgence in some places.

In 2015, Valerie Hunter Gordon, the inventor of the British disposable nappy, gave an interview about her long life. She said that in her generation, “Everybody wanted to stop washing nappies. Nowadays they seem to want to wash them again – good luck to them” (BBC News).

Actually the vast majority of parents nowadays do not want to wash them again, and they have not been sufficiently convinced to switch back to reusables. Cloth diaper babies are a small but growing contingent. But there is good news for women on another front. I led with that 1982 study which said 43% of fathers had never changed a diaper. Not even once. By 2000, it was only 3% who had never done so. Since we’re now 25 years on from that, I’m really hoping that a current study would show it where it belongs: at 0%.

Selected Sources

Babylist. “How Many Diapers Do I Need for Baby’s First Year?,” n.d. https://www.babylist.com/hello-baby/how-many-diapers-babys-first-year.

BBC. “BBC World Service – Witness History, When Disposable Nappies Were Invented, How the Disposable Nappy Was Invented,” July 13, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0g0q266.

BBC News. “Disposable Nappy Inventor Valerie Hunter Gordon Dies Aged 94.” October 19, 2016, sec. Highlands & Islands. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-37706756.

Dyer, Davis. “SEVEN DECADES of DISPOSABLE DIAPERS a Record of Continuous Innovation and Expanding Benefit,” 2005. https://145615380.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/145615380/Docs/default-source/absorbent-hygiene-products/edana—seven-decades-of-diapers.pdf.

Go Diaper Free. “Infant Potty Training in Indigenous Asia: How People Potty Their Babies in Countries without Diapers (Part 2),” April 14, 2020. https://godiaperfree.com/infant-potty-training-in-indigenous-asia-how-people-potty-their-babies-in-countries-without-diapers-part-2/.

Hall, Sharon. “Mothers of Invention: Marion Donovan (Disposable Diapers).” Digging History, September 22, 2014. https://digging-history.com/2014/09/22/mothers-of-invention-marion-donovan-disposable-diapers/.

Krafchik B. History of diapers and diapering. Int J Dermatol. 2016 Jul;55 Suppl 1:4-6. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13352. PMID: 27311778.

lemelson.mit.edu. “Marion Donovan | Lemelson,” n.d. https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/marion-donovan.

Matchar, Emily. “Meet Marion Donovan, the Mother Who Invented a Precursor to the Disposable Diaper.” Smithsonian. Smithsonian.com, May 10, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/meet-marion-donovan-mother-who-invented-precursor-disposable-diaper-180972118/.

Sanyhot.com. “Sanyhot :: History of the Diaper,” 2021. http://www.sanyhot.com/en/news/history-of-the-diaper.html.

Sharp, Mrs. Jane. The Midwives Book, or the Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered. Directing Childbearing Women How to Behave Themselves in Their Conception, Breeding … And Nursing of Children, Etc. [with Plates.]. London: Simon Miller, 1671. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A93039.0001.001.

Smithsonian. “‘Inventory Makes Chores Hassle Free’ Greenwich News.” Si.edu, 2025. https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?eadrefid=NMAH.AC.0721_ref15.

Soranus, Of Ephesus, and Owsei Temkin. Soranus’ Gynecology. Baltimore Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1994. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.547535/page/233/mode/2up.

The Art of Dressmaking. United States: Butterick publishing Company, 1927.

Tokat, Cansu, Nicholas C Rickman, and Cynthia F Bearer. “The History of Diapers and Their Environmental Impact.” Pediatric Research, July 9, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03347-5.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. “World Fertility 2024,” 2025. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2025_wfr_2024_final.pdf.

University of Warwick. “Research Punctures ‘Modern’ Fathers Myth – except for Nappies That Is…,” 2025. https://warwick.ac.uk/news/pressreleases/research_punctures_modern.

[…] say that it’s not a surprise which of the inventions I covered that did have female inventors: the disposable diaper and a poison to kill husbands. For obvious reasons, there weren’t a lot of male competitors to […]

LikeLike