Before I begin, I just want to announce that the results of the November Giving Poll are in. It was a very tight race, but the voters have spoken, and the winner was Women Helping Women, which provides services to abuse survivors. I have made the donation from Her Half of History. Thank you so much to those of you who voted, contributed, and supported.

Sewing by Hand

Sewing is very, very old. Needles have been found in Siberia and China dating back to 45,000 years ago (Pagano). Over the millennia, they traveled to or were invented again in almost every other region of the world. There was also plenty of technological innovation: from bone needles to iron needles, to different kinds of thread, to thimbles. But one thing that did not change is that someone had to push that needle into the fabric by hand and then they had to pull it out the other side, also by hand.

According to a lady’s magazine in 1782, it required 20,619 stitches to make a standard men’s shirt. To be perfectly clear, that’s someone’s hand pushing that needle through 20,619 times to make a very basic, straightforward article of clothing. Now imagine something bigger or more complicated or, heaven forbid, the man in your life wants two shirts.

The person pushing that needle was often a woman. She might be a mother making shirts for her children, she might be a wife making shirts for her husband or herself, and she might be a seamstress making shirts for anyone who will pay her. But it was not always a woman. A tailor was a man’s profession, and I have been unable to find any clear, universally applicable distinction between a tailor and a seamstress. Sometimes it seems that a tailor did men’s clothing and a seamstress did women’s, but not always. At times the distinction seems to be that a tailor got paid more for his work than a seamstress did for hers. Why are we not surprised?

But no matter who did it, the reality was every article of clothing took hours upon hours of labor to create. Clothes were expensive. They had become much less expensive with 18th century inventions in spinning and weaving, so by 17th century standards, they were cheap. But those early inventions did not help at all with the sewing bit, and by modern standards they were still unbelievably pricey.

The Early Machines

Inventors in France, the UK, and Austria were all aware of this fact. So there are multiple claimants for the inventor of the sewing machine, which is really a conglomeration of many inventions wrapped up in one package.

The first person who know definitely had multiple machines up and running was Bartolomé Thimmonier. In 1830 he had a contract with the French army to make standard issue uniforms in record time. Unfortunately, we will never know if Thimmonier’s machines could really have delivered the goods, because a mob of angry tailors broke in and destroyed his workshop. Twice (Museum of American Heritage; Cooper, 1).

Over in America, a man named Elias Howe was out of work due to chronic illness. His wife spent all day sewing to try to keep them alive, and Howe sat there thinking there has got to be a better way to do this. So he worked on it, and on September 10, 1846, Howe was granted a patent for his sewing machine. A couple of things about his invention would have startled anyone who knew anything about sewing. Howe completely abandoned the idea that machine sewing was supposed to duplicate like hand sewing. Instead of one thread in a needle that goes all the way through the fabric and back, it had two threads. The top thread went through a needle with an eye at the pointy end. It went part-way into the fabric where a shuttle caught the thread and looped it around a second thread before the needle was withdrawn. In other words, it worked exactly like a modern sewing machine does, and it creates what is called a lockstitch, very different from what a hand sewer would do with the same seam.

Elias Howe is often credited as the inventor of the sewing machine, but as I say it’s arguable because his was not the first sewing machine, and he wasn’t the first with most of the constituent parts either: the two threads, the shuttle, and the eye-pointed needle which did not completely pass through the fabric were all ideas that others had pursued as well.

But Howe was the man who emerged with a US patent and a semi-functional machine (Cooper, 19). The trouble was it was only semi-functional. In 1850 he had a handful of machines in a shop, but they had a lot of problems. He wasn’t having much luck in selling them.

Other inventors were busy at the problem too. Isaac Singer made one with an improved needle and a shuttle that moved better. Allen Wilson made one with a rotary hook on the bottom to better catch that upper thread when it came down and later, he added feed dogs, which are small, toothed metal bars that catch the fabric and steadily pull it through the machine for you.

All of these innovations are still features in sewing machines today. And there were other inventions too.

Bringing It All Together

Meanwhile Elias Howe was boiling mad. This was his machine and his patent, and here were all these upstarts capitalizing on it and doing it better at itthan he was himself.

There was only one solution: he sued. He settled with some companies and won his case against others and that meant they had to cease and desist, but Howe himself still couldn’t make a machine that anyone wanted to buy.

In 1856, capitalism found a business solution to this: The owners and inventors of various companies came together and said why don’t we do this together? Who needs healthy competition when we can buddy up and charge consumers whatever we want? They pooled their various patents for needles, shuttles, rotary hooks, feed dogs, etc., and they licensed out permission to use them.

Howe got $5 for every machine sold in the US, and $1 for every exported machine. He became a millionaire. Customers got the benefit of all the innovations in one package, and if the price was high, it was still cheaper than sewing everything by hand.

Multiple companies paid the licensing fees and did well, but the one with the most long-term name recognition is undoubtedly Singer’s. This is partly because his company made a good machine. But also because of innovative business ideas. The early sewing machines were heavy, clunky, expensive, and intended for commercial use. Singer made a lightweight model intended for home use by your ordinary housewife. That one hit the markets in 1858, and it didn’t come alone. It was accompanied by a media deluge of advertisements featuring gorgeously dressed models alongside their trendy sewing machines. Singer was the first person to spend a cool one million dollars on advertising (Stamp). Singer also hired women to demo and give tutorials, so no woman would feel it was beyond her to learn this baffling piece of complicated machinery. And very importantly, the Singer company also instituted a brand-new idea: purchase by installment. It was a very tempting offer for women who couldn’t justify the price tag out of their household budget, but if you can buy it on credit? Well, that’s different (Cooper, 35).

There is a reason why Singer’s company did so well. Though the reason isn’t necessarily Singer himself. In fact, his partner bought him out. It wasn’t Singer running it as they charged forward to victory in this market (Windham Textile). The Singer company (minus Singer himself) was also the same company that in 1889 added yet another important innovation to the machine: electricity. Earlier models were usually powered by a foot treadle, and electric machines were initially only for businesses because only businesses had access to electricity. That didn’t change on a large scale until after World War I. But Singer was already there, and ready.

Anyway, the point is that by the late 19ᵗʰ century sewing machines were not just available, they were common in first world countries. And that dramatically changed life for women, but not always in the ways you might expect.

The Sweatshops

Initial fears that the world’s seamstresses would be put out of business turned out not to be true. There was plenty of work for them. The difference was that the work was no longer something they did for long hours at pittance wages in their own homes. Instead, they came to the sweatshops and worked for long hours at pittance wages on the company sewing machines. This was not necessarily an improvement. Home may not always be safe, clean, and warm, but the sweatshops definitely weren’t. The most infamous case of this was New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Company, which hired hundreds of immigrant teenage girls to sew shirtwaists. They worked 14-hr days for $2 a day, and they had to pay for their own needles, thread, and electricity. There were no bathroom breaks or water breaks. The factory was on the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors, and the foreman kept the doors locked so he could inspect their handbags for stolen goods before they left. On March 25, 1911, the place went up in flames. Thousands of onlookers watched in horror as the fire brigade showed up with ladders that weren’t tall enough. Panicked girls jumped out the windows and fell to their deaths. The one and only fire escape collapsed under their weight. 146 people died, most of them teenage girls (American Experience).

This extremely public tragedy led activists like Frances Perkins (episode 14.18) to improve working conditions for American workers, but of course those new laws didn’t apply everywhere, and they still don’t today.

Ready-Made Clothing

The girls working for the Triangle Shirtwaist Company were making ready-made clothing, which in the grand scheme of things was a fairly new concept. To the extent that it existed at all in the early 19ᵗʰ century, ready-made clothing was for men so unfortunate as to have no wife, daughter, or even a paid seamstress on hand. That is to say, it was for sailors. Any man who did have access to a seamstress, paid or unpaid, was better off getting a custom fit because ready-made wasn’t any cheaper (Cowan, 74).

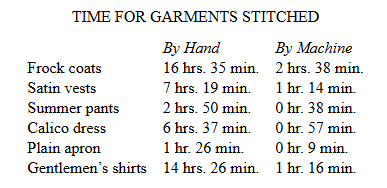

But by the 1860s, commercial machines could turn out a standard men’s shirt in 1 hour 16 minutes, which was enormously better than the 14 hours and 26 min necessary to do it by hand. Those figures were published in 1861, by the Wheeler and Wilson company, which made sewing machines (Cooper, 58), so their numbers may be skewed a little but there’s no doubt that the machine did it significantly faster.

The catch was that in 1861, most ordinary women didn’t have a machine yet. So what we really mean is that buying a man’s shirt from a warehouse was now faster and cheaper than having a woman do it for you by hand.

During the 1860s, the US army churned out machine-stitched uniforms and in the process they also collected some significant data on what standard sizing ought to mean anyway. It was a question for which data had never been necessary before, when everything was custom fit (Cooper. 59; Cowan, 74). By the 1870s most men didn’t need a wife to make their clothes for them. They could buy, and it was fine.

Such was not the case for women’s clothing. This is partly because data was not collected on standard sizes for women, partly because a woman’s size can vary much more dramatically (think pregnancy), but mostly because women’s clothing styles were very form-fitting. The earliest ready-made clothes for women were cloaks because cloaks were basically one-size fits all and everyone understood you might have to rehem it if you’re short.

The first ready-made dresses weren’t available until the 1880s, and even then they came with an expectation that you would alter them to fit once you got home. This was not much of an improvement over simply sewing it right in the first place, which is probably why the 1894 Sears Roebuck catalog did not have a single item of ready-made women’s clothing in it (Cowan, 75).

What this means is that women were still doing an awful lot of their own sewing right through the end of the century. And yes, by then, they might have owned their own machine, which helped. But not as much as you might think.

Middle-class women had always hired help to do the plain sewing while they reserved the cutting and decorative stitching themselves. The machine was great at plain sewing, so it eliminated the need to hire help. It did not eliminate the cutting and the decorative stitching (Cowan, 65 and more).

This meant the sewing was cheaper in household budget, and that’s good, but the housewife was personally responsible for more because she was now the only one working on it. Over time, the sewing machine, along with other labor-saving devices, changed the housewife’s status. Once upon a time, a middle-class housewife was largely a manager. Yes, she worked hard, but mostly at the tasks she assigned to herself. The most disagreeable or laborious tasks (like plain sewing) she assigned to others, and much of her labor was about hiring, firing, and overseeing the work of the household help (American Museum). Labor saving devices changed the housewife’s world. For one thing, she started working alone, where before there were often maids, daughters, and other women about, all deferring to her. I discuss the impact this had on women in episode 7.10 and episode 7.11.

Naturally, that only applied to women who were middle class housewives. And if you were one of the women who once deferred to the housewife, you went to the sweatshops.

Opportunity Knocks

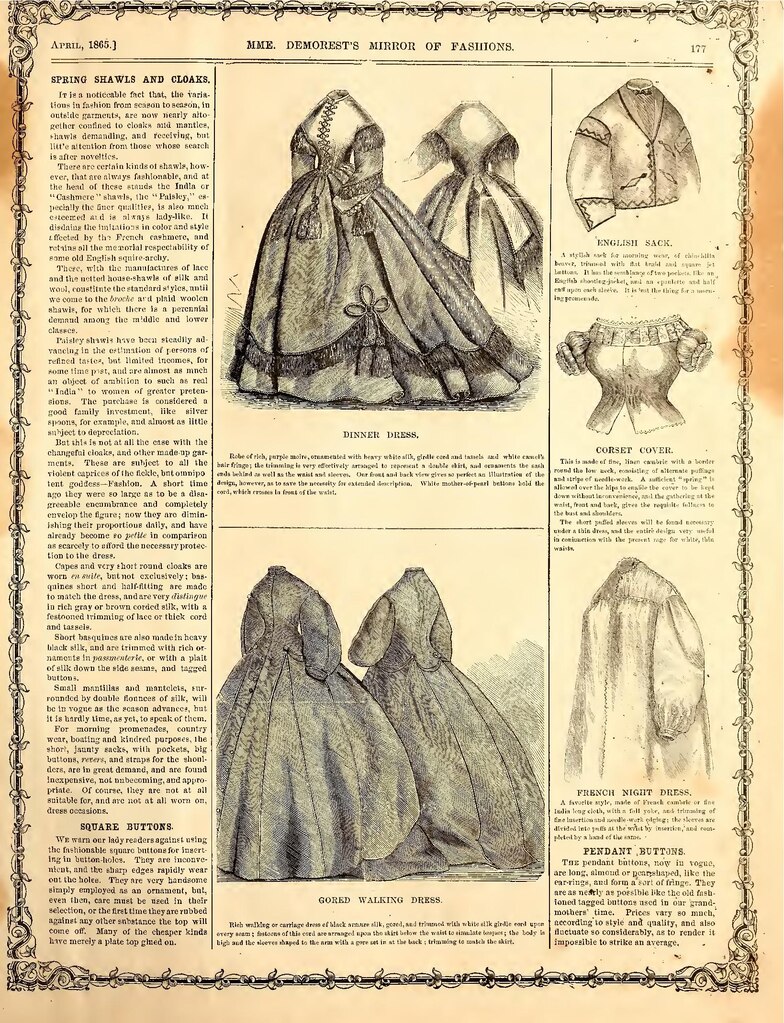

But while the housewife saw a decrease in status, some women saw opportunity. These included Ellen Curtis Demorest, who owned and ran a popular magazine called Madame Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions. The magazine told eager readers what the latest fashions were in places like Paris, London, and New York.

But Ellen’s real stroke of genius was inventing a way to mass produce patterns on large pieces of paper, which were then folded and inserted into the magazine so that you could recreate those fashions on your home sewing machine. Ellen Demorest sold millions of patterns. What she did not do was patent her idea or her process. A later competitor did. His name was Ebenezer Butterick, and if you’ve ever made your own clothes, there’s a reasonable chance you’ve used a Butterick pattern (Museum of American Heritage).

Another woman who capitalized on this new machinery was Helen Augusta Blanchard. She may not have invented the sewing machine or its most basic lockstitch, but she did invent the tech needed to make it do a zigzag stitch and a buttonhole stitch. Her designs initially helped in commercial settings, but they were eventually added to the home sewing machine too (Museum of American Heritage), and they’re a standard part of any machine you might buy now.

Of course, most women didn’t see that kind of success. But their mastery of the home sewing machine proved one thing: Women were perfectly capable of operating a complex machine. You might think that was obvious, but it wasn’t obvious to a lot of people in the 19ᵗʰ century. The sewing machine was the first complex machine available to such a large section of women. And they did just fine with it. And later on their sewing skills were considered directly applicable when another new machine became available: the typewriter. And that machine opened up the world of business offices to them. (See episode 15.5.)

The sewing machine continued to be a common possession for women until the mid to late 20ᵗʰ century, when globalization and trade agreements meant that even with a machine, you probably couldn’t make your own clothes as dirt cheap as you could buy them. Also, our fashions are different. We’ve decided we care about cheap and convenient more than we care about a perfect, tight fit. Sure, I know some people still struggle to afford clothes, but compared to the amount historical women used to pay for clothes, cheap is putting it pretty mildly.

So most of us simply own far more clothes than people in the past did, many of which we don’t even wear. Most of us have become as disconnected from the origins of our clothes as we are from the origins of our food. Possibly more so. There’s plenty of reason to be concerned about that. The conditions under which your clothes are made might not meet with your approval if you knew about them. But one thing I can be pretty sure of: no one pushed a needle through cloth 20,619 times by hand to make whatever shirt you are wearing right now. I would be surprised if a machine was not involved.

This podcast survives on the support of listeners and readers like you. If you’re able to contribute, please visit Patreon or Buy Me a Coffee. If you are on the hunt for the perfect gift for someone in your life, be aware that it is possible to gift a Patreon membership. They can get bonus episodes and ad-free episodes. Also don’t forget to vote for the topic of Series 16!

Selected Sources

Cooper, Grace Rogers. The Invention of the Sewing Machine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1968. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32677/32677-h/32677-h.htm.

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. More Work for Mother : The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Demorest, Mme. “Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly and Mme Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, 1865 April.” Internet Archive, 2025. https://archive.org/details/demorestsillustr00newy/page/192/mode/2up.

Eves, Jamie, Beverly York, Carol Buch, and Michele Palmer. “Sewing Revolution.” Windham Textile and History Museum – the Mill Museum, March 18, 2019. https://millmuseum.org/history-2/din-of-machines/sewing-revolution/.

Forsdyke, Graham. “History of the Sewing Machine.” International Sewing Machine Collectors Society. Accessed November 20, 2025. https://ismacs.net/sewing_machine_history.html.

Johnson, Susan. “‘Madame’ Demorest—the Woman at the Top of a 19-Century Fashion Empire.” http://www.mcny.org, April 15, 2020. https://www.mcny.org/story/madame-demorest-woman-top-19-century-fashion-empire.

Museum of American Heritage. “Sewing Machines.” Museum of American Heritage , 2019. https://www.moah.org/sewingmachines.

Pagano, Jacob. “Sewing Needles Reveal the Roots of Fashion.” SAPIENS, January 25, 2019. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/fashion-history-sewing-needles/.

Scott, Susan Holloway. “How Many Hand-Sewn Stitches in an 18thc Man’s Shirt?,” June 7, 2020. https://susanhollowayscott.com/blog/2020/6/7/how-many-hand-sewn-stitches-in-an-18thc-mans-shirt.

Stamp, Jimmy. “The Many, Many Designs of the Sewing Machine.” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Magazine, October 16, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-many-many-designs-of-the-sewing-machine-2142740/.

Vatz, Stephanie. “Why America Stopped Making Its Own Clothes.” KQED, May 24, 2013. https://www.kqed.org/lowdown/7939/madeinamerica.

I think the reason why Ellen Demorest did not submit her own patent for clothing patterns is because women were not allowed to submit patents.

LikeLike

Also, thank you for the reference to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. I recently read a book on the subject called Uprising by Margaret Peterson Haddix that was excellent.

LikeLike

[…] the first new invention she would have noticed was a sewing machine in her very own home. Sure, she still had to make a lot of clothes, but there’s a fair chance that a machine […]

LikeLike