Note on Images: Many of Frida’s works are still under copyright. I believe the use of them here is considered fair use because they are readily available on the internet (such as here and here and here and here), because this site is free and purely informational, and because it does not reduce the commercial value for the copyright holders. If that is not the case, please contact me and I will remove the images.

Would you describe your life as performance art? Frida’s was.

Many a woman has quietly adjusted her birth date to appear younger than she actually is, but Frida adjusted hers because being born in 1907 was boring. Why not be born in 1910? That would make her a child of the revolution (Garza, 24). Viva Mexico!

Her mother was from Mexico. Her father was an immigrant to Mexico, a Hungarian Jew, and it was probably he who taught Frida to be blunt and abrasive. He was a photographer by trade, but he didn’t like photographing people because he said, he did not like to make beautiful what God had made ugly (Garza, 11). He took photos of people anyway, and not always because he needed the money either. Most of the early photos of Frida are by him.

At age 6, Frida contracted polio because there was still no vaccine. Unlike millions of others, she was neither killed nor paralyzed, but her right leg was always shorter and thinner than her left, and she experimented with long skirts and even pants (gasp) to hide it. It didn’t blunt her ambition though. She was going to be a doctor and she was admitted to El Prepatorio, Mexico’s most prestigious high school. It was good that Frida liked to be the center attention because she was one of 35 girls in a student body of 2,000 (Garza, 27).

Just being a girl wasn’t enough attention for Frida, so she also joined a group of students known for pranks. In particular these students targeted the 36-year-old artist, Diego Rivera, who had been hired to paint murals on the walls of the school. Frida and her friends soaped the stairs before he would pass by, burst water balloons over his head, and stole his lunch. Now my question is: where was the school administration? Were they out to lunch or what? But Diego had his own method of self-protection. He carried a pistol and waived it at students, which just goes to show what a different world it was from the current US school situation. I mean, wow. Don’t try that in the modern world, okay?

Anyway, Frida’s life would upend completely before she finished school. On September 17, 1925, she was riding the bus with her boyfriend when it was hit by a streetcar. The boyfriend walked away almost unscathed. Frida was impaled by a handrail. She had three spinal fractures, a fractured pelvis, a dislocated shoulder, two broken ribs, and a shattered right leg and foot. She did not even receive immediate treatment because the medical personnel deemed her case hopeless and rushed to treat those they thought they could save.

Frida survived anyway. She spent months in the hospital, visited by neither her boyfriend (who cut off their relationship), nor her parents who had their own health and financial difficulties. Eventually she returned home, completely bedridden. The dream of becoming a doctor was too exhausting to contemplate.

In this series on Great Painters, we’ve had women who painted because they loved art, women who painted because it was the family business, women who painted because they needed money, a woman who painted for science, even a woman who painted because ancestral spirits told her to, but Frida is the only one who began painting because she was bored and in pain and she needed a distraction.

When she finally got out of bed, she decided to find out if her self-taught art skills were any good, and her chosen method of finding out was to track down her former victim, the muralist Diego Rivera. Never one to be shy, she marched boldly up to the bottom of the scaffold he was working on and asked him to come down and give her an honest opinion. He said the art was good. She said he should come to her home and see more of it. Diego was not a man to refuse a girl’s invitation. That’s why he was divorced. Twice. At any rate he came and his influence on her was profound. On his advice, she began painting in a Mexican folk art style and on Mexican themes.

Frida and Diego also bonded over politics, Communism, and social change. One of the earliest photos of them is at the May Day Parade of 1929. May Day, by the way, is International Worker’s Day and it’s called Labour Day in many countries, not including my own.

By August of 1929 Frida and Diego were married in a civil ceremony with only her father in attendance. The groom wore an ordinary suit and tie. He didn’t bother with a formal vest. The bride wore traditional dress: a long skirt and blouse and a rebozo, which is a Mexican shawl. She had borrowed it all from the family maid.

Frida’s father was pleased with this match. Diego was a success. He had a good career. Frida was going to have medical bills for the rest of her life. A husband with money was an excellent idea. Frida’s mother was more critical, and to be honest, she had reason for concern. Diego was twice Frida’s age, practically twice her size, a known womanizer, an atheist, a Commie, and in the eyes of the Catholic church, still married to his first wife, because divorce was not a thing.

The wedding party may well have cemented her opinion. Diego got raging drunk and his ex-wife showed up. Frida spent her wedding night in tears.

Afterwards, the bold girl she had been seems to have got lost, as she tried to figure out how to be a wife. Especially a wife of a man like Diego. She kept her maiden name (Kahlo), but she dressed and cooked to please him. He spent his attention on his work, not to mention other women.

Frida became pregnant, which was fraught with complications. Her pelvis was not in good condition. It was likely she could not bring a child to term. Then there was the fact that Diego didn’t want to be a father. He was already botching fatherhood with his previous wives. He saw no need to repeat the experience. At three months along Frida agreed to an abortion, which was legal, but she cried inconsolably (Barbezat, 56).

Diego had other troubles (both professional and political), so he was happy to accept a new commission in San Francisco. In 1930, they left Mexico on the first of their journeys together. San Franciscans loved Diego, and he loved them back, sometimes in a physical sense.

Frida hated it. She was appalled by the evidence of the Depression, and the long lines at soup kitchens while the rich threw money at Diego. She was also bored. She had nothing to do and her foot hurt. As before, she turned her boredom into painting, including her first painting with a surrealist element. It was a portrait of the Californian Luther Burbank. If you’ve not heard of him, you’ve still benefitted from him. Burbank is the horticulturalist who brought you the Shasta daisy, most of the peach varieties you’ve ever eaten, most of the potatoes you’ve ever eaten, especially if you are eating them frenched and fried, and a host of other hybridized crops. Frida painted him growing directly out of a tree, a hybrid of himself, if you like. With trademark Frida gruesomeness, we see the tree’s roots entwined in a corpse underground, which actually was how Burbank had chosen to be buried.

Frida and Diego returned home briefly, and then it was off to New York which Diego loved even more than San Fran, and Frida hated it even more. If she had been a Mexican nationalist before, now she was really a nationalist. She emphasized it in her dress, which New Yorkers found charming (again, her life is a performance). But when they moved on to Detroit, the people there found it shocking. Ditto with her language, her politics, and her religion (Garza, 62).

To make matters worse, she was pregnant again. None of the previous factors had changed, except that she was now in a country where abortion was illegal. She reached out about it anyway, but then changed her mind and decided to keep the baby and risk the medical complications.

She miscarried badly and spent two weeks in the hospital, bleeding and crying and reading at medical textbooks about fetuses.

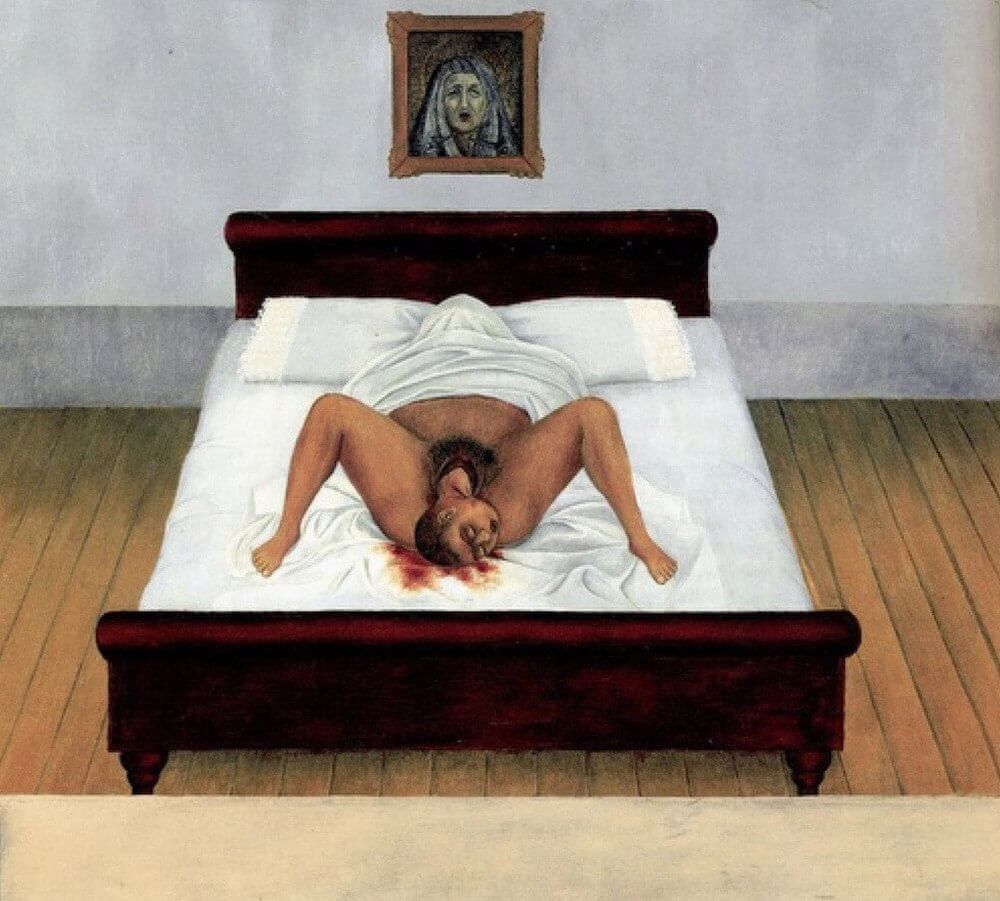

When she got out of the hospital she painted Henry Ford Hospital. The title makes it sound like a picture of a building, but it is anything but. It’s a self-portrait of sorts, but she’s nude on a bed in a pool of blood with threads connecting her to a fetus, a pelvis, a snail, an orchid, and a piece of machinery. The Detroit skyline is in the distance. It has been called an anti-Nativity scene.

She followed it up with a painting called My Birth, where she paints her mother giving birth to her in a full frontal view, baby midway through the birth canal.

These paintings were shocking at the time, and they are still shocking now. Remember two posts ago when Paula Modersohn-Becker was weird for painting herself nude and pregnant? Well, in comparison with Frida, Paula looks downright modest, even demure. Frida was painting experiences that millions of women had had, but few spoke about. There are (I am told) Aztec precedents for such art, but none in the Western world as far as I know. If Modersohn-Becker had stripped the feminine nude of the masculine gaze of desire, Frida had stripped it so far it was into negative territory: a reclining female body that many a man would actively recoil from. Many a woman too, for that matter.

Frida was using art to process what had happened to her, and at the time, Frida did not intend her paintings to be shown to anyone outside her own circle of friends. She wasn’t a professional. As far as the world was concerned, she wasn’t an artist. She was just the wife of an artist. And she was a wife who longed to go home to Mexico, something Diego had no intention of doing.

She painted her homesickness in Self Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States. She stands, fully clothed this time, with the plants and pyramids of Mexico on one side and skyscrapers, industrial smoke, and an American flag on the other. It was obvious which one she preferred, and in the end, Diego was forced to grant her wish.

His downfall came after he was back in New York, doing a mural for the Rockefeller family, the oil tycoons. In his mural, Diego painted in the face of Lenin. As in Vladimir Lenin. As in revolutionary Communist, leader of everything an oil tycoon definitely wasn’t, everything Americans in general were totally sure would destroy their God-given rights and freedoms, not to mention their pocketbooks.

Rockefeller asked Diego to paint Lenin out. Diego blustered about artistic integrity, free speech, no compromising my principles, and you can’t make me! Rockefeller said I’m the one paying for this free speech, and you’re fired.

Diego’s fall from grace in America was Frida’s ticket home. An unhappy Diego and a thrilled Frida moved back to Mexico. They bought a house, or rather, they bought two adjoining houses, connected by a walkway, the better for Diego to carry on affairs, which he proceeded to do, including with Frida’s sister.

In fact, the homecoming let her down badly. She lost another pregnancy, her appendix was removed, and her foot was operated on. One of my sources (Garza) suggests that every time she began to worry she was losing Diego to another woman, her health worsened, whether because she truly did have a physical reaction to this or because she insisted on unnecessary treatment as a means of getting his attention.

This time she considered divorce. But she had the age-old problem for women in unhappy marriages: he had all the money. Eventually they patched it up by agreeing to have an open marriage, which it definitely already was on his side, and may have been on hers. She became a brilliant glittering hostess for artists and writers, with bright costumes, and she had many affairs with both men and women.

If that sounds like a great life to you, let me just add that she was drinking heavily, and she had still not sold any paintings.

In 1937, Frida and Diego welcomed their most famous guest: Leon Trotsky, the revolutionary Marxist who had opposed Joseph Stalin and lost. Stalin was not in the mood to give up kicking a man just because he was lying on the ground, and Trotsky was perpetually at risk of assassination. Additional security had to be installed on the house. While Trotsky and his wife were house guests, Frida had an affair with him while his wife grew colder and colder. One gets the sense that despite the pain Frida had felt at Diego’s many infidelities, it never occurred to her not to inflict the same on another woman.

Diego was an abysmal husband in many ways, but one thing he was good at was championing her art. On his advice Frida finally exhibited her work, extremely private scenes and all. The most painful moments of her life were now on display for anyone to see and comment on. (Life as a performative art, remember?) To her astonishment, some of her paintings sold. Until now it had never occurred to her that she could be financially free.

In October of 1938, she had a solo exhibition in New York which was well attended, well reviewed, and financially encouraging. To everyone who asked about her relationship with Diego, she gave a different story because she enjoyed seeing people’s reactions. From New York she went to Paris which didn’t go as well. The French in 1938 were not especially interested in looking at art, as they were busy looking nervously over the backyard fence at Germany. But still there was plenty to be proud of: the Louvre Museum bought one of her paintings. Take that, Diego!

When she got home, she and Diego divorced. Why now? With so much water under the bridge? Well, it’s not clear. Diego said it was a divorce of legal convenience (whatever that means), they got along just fine. Frida said they did not get along, and it was personal. He said divorce was the best thing that ever happened to Frida’s art because she became more prolific. She said she was miserable and suicidal. She wrote that “there is nobody in the world who has suffered as much as I do” (Garza, 96-97). Which is possibly just a little exaggeration, but there is no doubt that she was living a very hard life.

Naturally, she did not shy away from difficult topics, and she painted her grief multiple times. On the day her divorce was finalized, she completed The Two Fridas, in which she is on the canvas twice, once in Victorian dress, once in traditional Tehuana dress. An anatomical heart is visible on both figures, with veins that connect and then bleed directly onto her dress. With her usual lack of consistency, she explained this in multiple ways: one Frida was the one Diego loved and the other he did not. Or that this dual portrait was somehow a representation of solitude. Or that it was Mexico: both indigenous and European, both bleeding (Barbezat, 120).

She now needed to make money and one of her friends gave her advice on how to be more marketable. He said she “shouldn’t paint such gloomy and personal things like pelvises, hearts, etc.” Frida did not take this well, she wrote irritably “What the hell does he want me to paint? Angels and seraphim playing the violin?” (Barbezat, 125). She either didn’t know or didn’t care that a lot of artists had made a very good living by painting angels and seraphim. And that was her friend’s point.

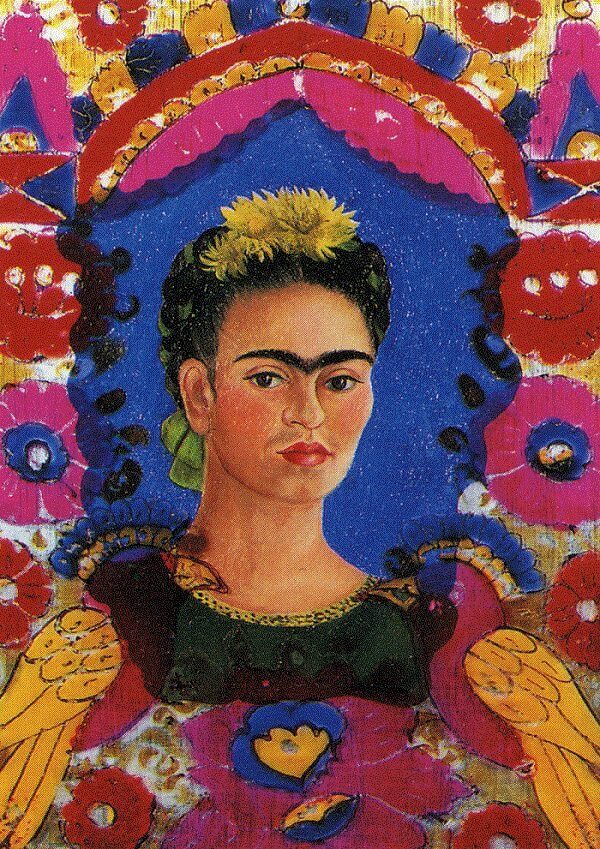

Frida never claimed the label of Surrealist, but she is the epitome of the movement to some. There are technical definitions of surrealism, but she defined surrealism as “the magical surprise of finding a lion in a wardrobe where one is sure of finding shirts” (Barbezat, 111). One thing is sure, there are a lot of magical surprises in her paintings. Even the ones that don’t have obvious magical realism are not a direct reflection of reality. For example, she usually painted herself with the famous unibrow. I’ve looked at photos of her, and I can confirm that she did not in fact have a unibrow. She just chose to portray herself that way.

Despite the divorce, she was still in contact with Diego. She still managed his household in fact and told a friend that Diego had divorced her because “I always want to have his papers and other things in order and he likes them in disorder” (Barbezat, 124).

As usual when things were rough with Diego, her health deteriorated and the doctor’s advice did nothing to ease her pain. Diego brought her to San Francisco to consult a doctor there, and he recommended a novel treatment: no more alcohol and remarriage. Diego was revolting in many ways, but she needed him. Diego gamely agreed. Frida was not so sure.

She considered his proposal while on a one-month fling with another woman. Eventually she said yes. The course of true love never did run smooth, and particularly not for this couple.

Back in Mexico they didn’t even try to live together. She lived in her family home; Diego came around for meals. Some of the time. She transformed the house itself into living art: plants and animals and traditional Mexican straw mats and papier-maché figures.

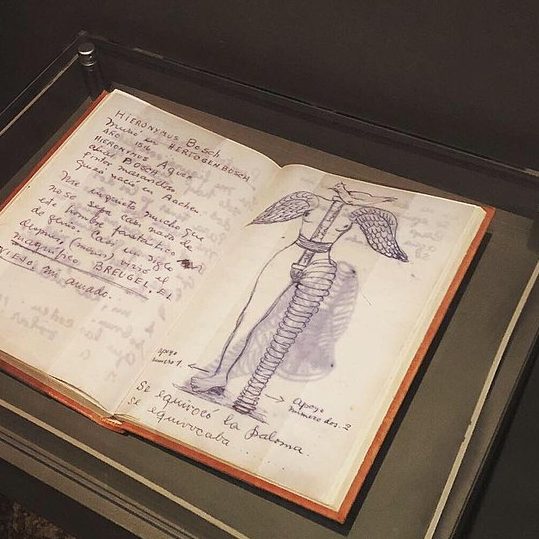

She taught students there, which she found awkward since she herself had never had an art class. She began a diary, which has as much art in it as it does words. She painted more self-portraits. One of them was the Broken Column, which has her torso split open to display a broken classical architectural column for a spine, a depiction of her increasing back pain.

In the late 40s and early 50s she grew increasingly weak and had more and more operations.

In 1953 she had her first solo exhibition in Mexico. She arrived by ambulance, was carried in on a stretcher, and was placed on a bed in the center of the gallery.

A few months later, her right leg was amputated. In her diary, she depicted herself as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, which she had probably seen in the Louvre on her trip to Paris. “Feet” she wrote, “what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?” (Kahlo, 274).

But despite her brave words, she felt she was losing the battle of life. The last passage in her diary reads “I hope the exit is joyful—and I hope never to return” (Kahlo, 285).

She died a few days later, after insisting on attending a protest rally against her doctor’s advice. She was 47 years old, though she only claimed 44. Officially her death was natural. Some have speculated it was suicide.

At the time, only people who hung out with artists knew who she was and most of those still knew her as the wife of Diego Rivera. But her fame would soon outstrip his. Museums, books, and documentaries abounded. She got major promotion by the feminists, the Chicanos, the disabled, the LGBT. All of them saw her as a sort of secular saint, a martyr to the cause of achievement despite suffering and persecution. Since she had done much of the mythologizing herself, they were only following her lead.

She gained a cult status compared with the likes of Elvis and Marilyn Monroe. Quite a feat for someone who never made a movie or a hit album and whose art is actually quite hard to look at. The word ugly comes to mind, but it’s not so much that her 200ish paintings are ugly, as that she chose to paint the ugly things of life. Her father had not wanted to make ugly people beautiful. Frida just went ahead and painted them ugly. In the words of one reviewer “pain was her visual vocabulary” (Mexico 1900-1950, 175). Some people resonate with that.

Madonna bought the painting My Birth and told the press that anyone who didn’t like it was off her friend list. Which is just one of the many reasons that I’m not friends with Madonna (Barbezat, 160). Yeah, sorry, I find Frida historically interesting, but I don’t need to own My Birth, even if I could afford it, which I can’t.

Frida’s devotees have even inspired whole new words like Fridamania, Fridolatry and Kahloism. They’ve also sold an incredible number of magnets, mugs, tote bags, key rings, coasters, posters, throw pillows, phone cases, sticky notes, socks, candles, blankets, clocks, hand towels, even a Frida-inspired rubber ducky. No doubt she would be astonished at the sheer volume of tacky trinkets her work has inspired. But then she never shied away from the limelight, and I suspect she would have been delighted.

Selected Sources

Barbezat, Suzanne. Frida Kahlo at Home. London, Frances Lincoln, 2016.

Caldwell, Ellen C. “Fridolatry: Frida Kahlo and Material Culture.” JSTOR Daily, 16 June 2016, daily.jstor.org/fridamania-frida-kahlo-and-material-culture/.

Chicago, Judy, et al. Frida Kahlo: Face to Face. Munich ; New York, Prestel, 2010.

Garza, Hedda. Frida Kahlo. New York, Chelsea House, 1996.

Kahlo, Frida, et al. The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. New York, H.N. Abrams ; México, 2005.

México 1900-1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco and the Avant-Garde. Edited by Agustín Arteaga, Dallas Museum of Art, 2017.

Frida Kahlo’s life was a captivating mix of pain, passion, and artistry. Her unique journey from a tragic accident to becoming a celebrated painter is inspiring. How do you think her experiences influenced her art? Have you seen any of her paintings in person, and if so, what emotions did they evoke in you?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frida refers to “A lion in a wardrobe”. Had she read C. S. Lewis’s work? Did she find it surrealist? At times, it does get very weird, but this would be the first time I have connected “Surrealist” to his work.

I wonder, too, if Frida likes C.S. Lewis’s work. And how much of it she did read, if she did at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I wondered that about that too because I love C.S. Lewis, but I double checked the dates and I don’t think it’s a reference to him. She wrote that comment in 1944. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe wasn’t published until 1950. He had written a lot of books before that, and maybe she knew about them, but I don’t think there’s anything about a lion or a wardrobe until then.

LikeLike

[…] captivating narratives to Mary Cassatt‘s tender depictions of motherhood, and Frida Kahlo‘s unapologetic self-portraits, these artists have left an indelible mark on art history. But […]

LikeLike

[…] they were never allowed out of the house and yard. Then the Bolsheviks took power under Lenin and Trotsky. The Bolsheviks had no interest in paying the household expenses of an ex-tsar. Quality of life […]

LikeLike