It was a bright sunny day on July 4, 1862, in Oxford, England. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, an Oxford math professor, decided to take a friend and the three girls who lived next door on a picnic, where they begged for a story. Charles obliged and spun out a fantastical yarn, naming his protagonist after the middle child, the 10-year-old Alice.

Only the Alice in the story fell through a rabbit hole into a world both strange and wonderful. The real Alice liked her story so much that she asked Dodgson to write it down, a process that took him a year and a half. But in 1864, he presented her with the original manuscript of Alice in Wonderland to her for Christmas. It was published in 1865 under his chosen pen name, Lewis Carroll.

Alice in Wonderland was revolutionary. It is the original piece of children’s literature, at least in its modern incarnation. It was unlike any of the books I talked about last week because its purpose was purely to spark joy, both for the children and also for the author. It’s playful and fun, and if there is a moral lesson to be learned it’s buried deep (Meigs, 211). (Actually, I have heard spiritual lessons use quotes from Alice to prove a point, but nevertheless, whatever moral lesson it’s got, is subtle enough it’s possible to entirely miss it.)

The Wizard of Oz, Mary Poppins, Beatrix Potter, the chronicles of Narnia, Dr. Seuss, all of these classic books to come (plus many, many more) owe a debt to Lewis Carroll for breaking the didacticism of earlier books for children and celebrating fantasy and imagination and a world where nothing was inevitable, not even the laws of physics. Children’s literature would never be the same again.

Little Women

And yet, hard on its heels came a completely different tradition in children’s literature. Louisa May Alcott was the daughter of the noted transcendentalist Bronson Alcott. She had grown up in a tight family with strong and sometimes unusual opinions about morals and values. She had already written and published sketches based on her brief experience as a nurse during the American Civil War, but in 1867 her publisher asked her to try writing a book for girls. The result was Little Women, which Louisa herself initially thought was dull (Meigs, 229). The public disagreed.

Like Alice in Wonderland, Little Women was an immediate and phenomenal success, but for entirely different reasons. Alice offered cleverness and freedom from reality. The March girls in Little Women were unmistakably real (they were, in fact, Louisa Alcott and her sisters), but readers then and now have loved them for their warmth and closeness, for the way they are good-hearted and really want to do the right thing but also the way that they are deeply human and frequently fail to do the right thing. (Don’t we all?)

The intimate life-at-home book would become a standard in children’s literature, especially for girls. And books like L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, and Beverly Cleary’s Ramona books (plus many, many more) would all owe a debt to Little Women.

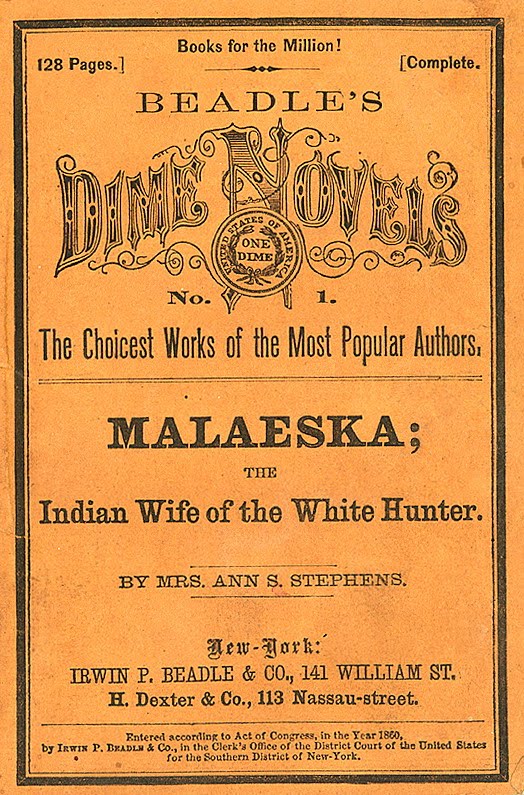

The Dime Novel and the Penny Dreadful

And still, right at this same time period there were other developments in children’s lit. It’s just less likely that you’ve read them. In 1860, the Beadle publishing company produced a book called Malaeska, or Indian Wife of the White Hunter by Ann S. Stephens. It sold 300,000 copies, and within five years had been translated into five languages.

That in and of itself would not be enough to make it worth mentioning, but it is the original dime novel, or what the British would call penny dreadfuls. Dime novels were published cheap. They came only as paperbacks, and not very well-made paperbacks at that.

If you were never assigned to read Malaeska in school, well, there’s a reason for that. Here is a quote:

‘Touch but a hair of her head, and by the Lord that made me, I will bespatter that tree with your brains!’ Thus spake William Danorth, white hunter. Many a dusky form bit the dust and many a savage howl followed the discharge of his trusty gun!’

Ann S. Stephens in Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter

Nineteenth century critics mostly didn’t notice the racism, but they most certainly did notice the way all those bulging arm muscles, strapping chests, smug superiority, and gratuitous displays of mindless violence set the hormones bubbling in the girls (and boys) who read them. Dime novel publishers were going for neither imagination and clever wordplay (like Alice) nor the intimacy of a refined home life (like Little Women). Nope, dime novels were formulaic and superficial and clunky. In the modern world they’d be written by AI, and AI would do just fine at generating them. In fact, the writers practically were AI in a 19th century sense. Publishers swapped out one writer for another without any noticeable change in the output, and the deadlines were intense (Hunt, 261).

The original dime novels were Westerns, a genre we associate mostly with boys and men, but it was not only boys who read them. Malaeska was actually a reprint from a story first published in a magazine, and the magazine in question was The Ladies Companion. It was written with girls and women in mind. Mostly it was an adventure story, but if you want to look for a moral, then the moral was don’t make an interracial marriage, a lesson which The Ladies Companion undoubtedly approved of.

In addition, the dime novel publishers soon found there was money to be made in other areas too. From Westerns, they branched out into non-Western adventure and romance. Reading girls particularly enjoyed dime novels like Only a Mechanics’ Daughter: A Charming Story of Love and Passion or The Unseen Bridegroom.

The literati turned up their noses at the dime novels, but working-class girls loved them. Probably a high percentage of upper-class girls also loved them, if they were unsupervised long enough to get their hands on them. Many of these books were written by women, and they sold considerably better than books by the likes of Nathaniel Hawthorne or Herman Melville (Carr).

The heyday of the dime novel ended in the early to mid-20th century, but its influence is not dead: if you’ve ever enjoyed a Western, a romance, a rom-com, a comic, a manga, a horror, or even a celebrity gossip magazine, it probably owes a debt to the dime novel and the penny dreadful (Pope). And I will hasten to add that all of those genres do have some shining examples of really good writing, whatever the critics say.

Picture Books

Also at the same time (still in the 1860s), children’s books were benefitting from dramatic improvements in the techniques of color printing.

Back in episode 10.6, I talked about how Maria Sibylla Merian sold her books with illustrations of the natural world, and they came in two versions: the black and white version (which was cheaper) or the colored version, each of which was colored by hand. Maria herself did the first editions, but coloring books was also an industry. An industry in which children worked, in fact. Child workers were assigned colors, so one would fill in the red bits, and then pass it on to the yellow child, and then the blue child, etc. (Bingham, 141). Even with the exploitation of children, that was expensive, so most books didn’t have a lot of pictures and most pictures were left black and white, and few of them were what you’d call high artistic achievements.

That was normal until the 1840s, when lithography (which uses chemical processes to etch an image onto a stone or metal plate) became common. Wood block engravers also improved their methods. And by the 1860s, a British publisher named Edmund Evans was producing what he called toy books, but I would call children’s picture books.

Evans didn’t want the third and fourth rate artists who had generally produced book illustrations before. He was interested in real beauty, and he cultivated his artists. His name was new to me while doing this research, but two of his artists’ names were not.

The first was Randolph Caldecott, whose illustrations were such a success that in the US there is an annual award for the best children’s picture book called the Caldecott Medal. The second was Kate Greenaway, whose work was so popular she was a household name not only in her native Britain, but also in the US, Germany, and France. The British annual award for best children’s picture book is the Greenaway Medal (Bingham, 144).

Both Greenaway and Caldecott produced books that were beloved by girls at the time, and while those books are not generally well known among children today, it was they who raised the expectation that a small child could have a beautiful and engaging book to look at, even before they knew how to read the words. Maurice Sendak, Dr. Seuss, Eric Carle, Sandra Boynton, and many, many others are following in their wake.

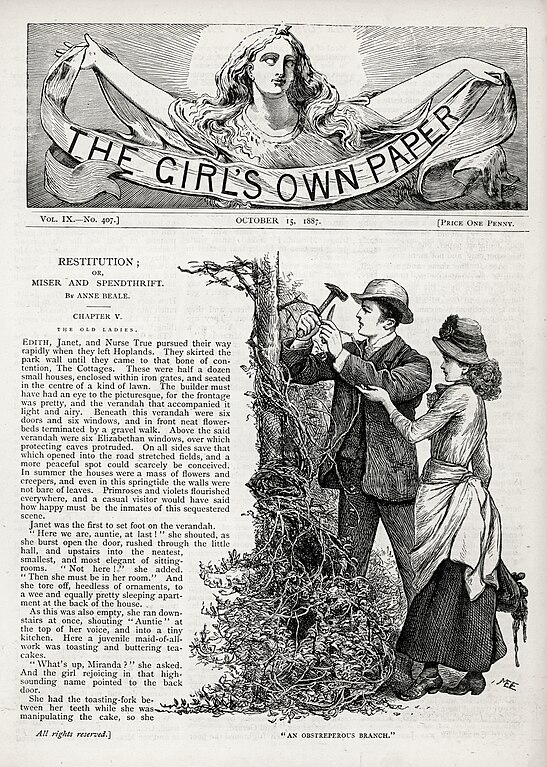

Periodicals

Also at exactly the same time (the 1860s strike again), the reading girl saw her access to magazines explode. Children’s magazines had actually been around for quite a while.

All of the early magazines were dominated by moral lessons and sentimental verses (Bingham, Abadie, 4). There were some moderately successful ones, like the Juvenile Miscellany, run by Lydia Maria Child, who we met in episode 11.5.

The Youth’s Companion lasted longer, and unlike the dime novels, it featured tales written by authors you’ve likely heard of, like Mark Twain, Jack London, Louisa May Alcott, Washington Irving, Edith Wharton, and Willa Cather (Abadie, 9). Periodicals for the young was a serious place to break out into a serious writing career.

All of those periodicals existed before the 1860s, but they (and others) also benefitted from the improved printing methods (pictures are just such a great draw) and the massively increased market for reading material that would entertain, rather than just instruct. Most of the new periodicals were aimed at both boys and girls, with most of the rest being aimed specifically at boys. Girls were not so well provided for (Dixon, 4), as publishers seemed to think they were not a viable market.

That was a major misjudgment, as would be proved in 1880 when the British publisher of The Boy’s Own Paper took a gamble on a new line called The Girl’s Own Paper. It quickly sold better than the boy’s version (Dixon, 5). Notable authors who appeared on its pages included L. M. Montgomery, author of Anne of Green Gables, and Baroness Orczy, author of The Scarlet Pimpernel.

Periodicals were also, in some ways, the inheritors of the courtesy books I mentioned last week. The ones that told you how to behave yourself. Only now, they could do so in the form of advice columns. Girls wrote in with their problems, and the editor (or more likely a low-paid lackey) wrote back with advice, and I am preparing a bonus episode on advice from the Girl’s Own Paper to be released in the coming week. You should totally sign up on Patreon or Into History to listen to it. Links in the show notes and on the website.

Libraries

The fact that any of these formats were directed at working and middle class girls is proof that the price of printing was below the wildest dreams of Gutenberg, but even so, there were many who could not afford them, Or there were many, like myself, who can afford books, just not in the enormous and gluttonous quantities in which I require them.

And that is why libraries are the best places on Gods’ green earth. Libraries in the early 1800s did begin to have children’s books (Meigs, 46), but they were pretty much totally ineffective at getting those books to children.

For one thing, they weren’t free. They were supported by subscriptions collected from the members. If a working class girl can’t afford books, she probably also can’t afford a membership. For another thing, the population was mostly rural and the libraries were mostly urban. And for another thing children often weren’t even allowed in libraries, on the theory that they would disturb the adults (Meigs, 417), and damage the books.

According to the American Library Association, the very first free modern public library funded by the local government opened its doors in 1833, in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Other sources give other dates and locations, so I don’t really know, but the concept spread.However, it was not until 1877, that Mrs. Minerva Saunders, a librarian in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, set aside a corner in her library, specifically for children. She got special chairs for them, and she allowed children to have their own accounts and to borrow books. Mrs. Minerva Saunders is truly one of the great minds of her age (Meigs, 416). By 1900, many libraries had followed her example (Meigs, 419).

The push for libraries for children was in part a reaction against the dime novel. The theory was that if kids could borrow quality books for free, they wouldn’t be so enraptured with the 10 cent trash. (Meigs, 417). I’m not sure that theory panned out, but I support the library initiative.

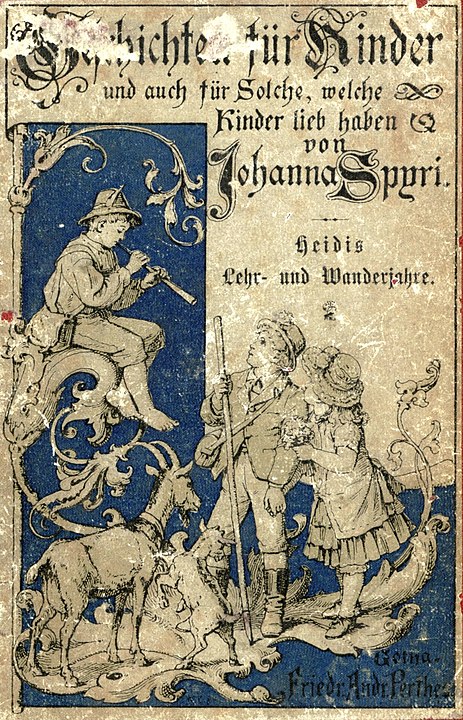

International Books

By 1900, we’re talking about an absolute flood of written words, and you may well be asking, surely, not all of the words were written in English? And indeed, they were not. As I discussed last week, children’s literature was in some ways a British invention (more on that in a bit), but the rest of the world was catching on.

By the turn of the 20th century, the reading girls of other nations had some real gems to choose from. In Germany, the brothers Grimm had published many editions of their household tales for children. German reading girls also had the tales of ETA Hoffmann, who wrote a strange story called The Nutcracker and the Mouse King in 1816, well before Alice in Wonderland, though it certainly shares some common elements (Hunt, 735). In Switzerland, Johanna Spyri wrote the internationally famous Heidi about girlhood in the Alps.

In Italy, Pinocchio was having adventures (including being hanged and then brought back to life, a scene Walt Disney seems to have missed (Hunt 1758). The French had not only Charles Perrault’s Mother Goose tales (not originally intended for children), but also Madame Leprince de Beaumont’s Magasin des Enfants, which was intended for children and included the shortened version of Beauty and the Beast. (Hunt, 719). I am mentioning only the ones that I think my English-speaking audience may have heard of. There were lots of others.

However, you may have noticed that all of those titles are from major European languages. In Denmark, Hans Christian Andersen, who didn’t even like children, had written some of the world’s most beloved children’s stories (Tatar, 45). But for the most part, languages from smaller European countries had a major problem. Without a large population, the number of children interested in books is small. Therefore, the prices are high. Therefore, the market is still smaller because most children cannot afford them. Therefore, the price is still higher. It’s a cycle, and a problem that continues to this day (Hunt, 656).

As for the world outside of Europe and the European-dominated colonies, they sometimes had that problem of many languages, each spoken by a relatively small population, but sometimes they had huge populations. And there were a few attempts to provide for those kids. In India, Raja Shivprasad wrote books for children in Hindi (Hunt, 810). But for the most part these countries either had no strong publishing industry at all. Or they were struggling under the pressure of European expansion, either politically, militarily, or at least financially. Or they had simply not yet transitioned to thinking about children as a distinct group within the reading public. As far as I can tell, even countries like China and Japan, who had substantial literate populations, were publishing very few books with girls as the target audience.

Which brings us at last into the 20th century, worldwide.

The 20th Century

Publishing in the 20th century faced wartime shortages and multiple economic downturns, all of which impacted books for girls, but by far the larger impact came from the new availability of other ways to get your story fix and your information high, by which I mean radio, movies, TV, video games, and the Internet, all of which were predicted to end reading, corrupt the young, degrade society, and end civilization as we know it. Funnily enough, no one seemed to remember that the same arguments were leveled at reading in previous centuries. (Remember Fordyce from last week? Remember the critics of dime novels from this week?) Somehow the reading girl managed to hold on to her books throughout all this, and indeed children’s lit metastasized in multiple ways in the 20th century.

On a minor, but significant to me note, the genre of historical fiction was invented. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books (written 1932-1943) were the most famous ones directed at girls, but they were not the first nor the last examples.

For another thing, the non-European world got into the game. The first full length children’s novel written in Chinese was published in 1932 (Hunt, 834). Kamel Kilani, an Egyptian author, published many children’s books in Arabic between 1930 and 1950 (Hunt, 788). In 1966, the Empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi, wrote a children’s book herself called The Daughter of the Sea. It was the first publication of a new institute intended to promote children’s literature. Despite substantial political changes, including for the empress, the institute kept working (Hunt, 792). In Kenya, a writer named Charity Waciuma pioneered children’s lit for her country in 1966 with Mweru, the Ostrich Girl (Hunt, 799).

There are countless other examples from nearly every other country on earth, and yet there remain problems. As late as 1984, an advocate for books in Ghana was able to say “Most children in Africa see and handle books for the first time only in the classroom… In most African countries the only books young people have access to are textbooks” (Hunt, 797). But according to the nonprofit Books for Africa, forty percent of African children to this day don’t even read textbooks because they aren’t in school at all. I am willing to bet that over half of those are girls.

Young Adult

The last 20th century change which I will mention is the split off of Young Adult from children’s books. That distinction took a long time. Some books had always been targeted that way. Little Women certainly wasn’t read by 5-year-olds. But not until the 1950s were books written and published with teenagers in mind specifically (Hunt, 388). That’s not surprising timing. As we will see in a few weeks, that’s exactly when society at large noticed that teenagers exist.

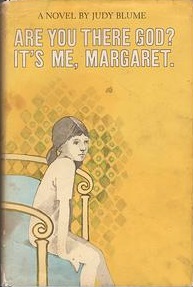

The split between children’s fiction and Young Adult fiction and later the insertion of middle grade fiction in between them allowed writers to discuss things that had most certainly never been included in earlier children’s lit. Like when Judy Blume was open about menstruation in Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret, published in 1970. Let’s just say the March girls in Little Women surely had periods, but you’d never know it from the text. That was another big change during the 20th century. But the boundaries between these categories are fuzzy.

Kids have been reading books intended for older people since kids learned to read at all, but by the early 21st century, things were also going the other way around. The hottest books in any genre were Young Adult, by which I mean Harry Potter, Twilight, the Hunger Games (all of them written by women, by the way). They didn’t get to their cult status on the basis of young adult spending power. Nope, according to Publishers Weekly a full 55% of the works that publishers have said are for ages 12-17 are in fact being published by those of us who are 18 and older. Other estimates are even higher. And we are not buying them for the teenagers in our lives, a full 78% of us are buying them for our own consumption, and I place myself firmly in that class.

To some this is a matter of concern. After all, if the consumers of Young Adult are actually just adults, then we’ve basically coopted the genre, stolen it as it were, from the youth it was meant to serve because publishers will make decisions based on our wishes, not the teen’s needs. Basically, it’s a rejection of the whole trend of children’s lit which was supposed to be about recognizing the beauty and specialness of childhood.

Maybe so, but as an adult, I’ll say what it is is a missed opportunity. If so many of us old fogies like Young Adult lit, then obviously the adult publishers are not providing us with something we want. Just a thought.

Whatever the format, the reading girl is now drowning in a sea of choices. Never before has there been so much to read in so many genres and so many formats. Sure, most of it is trash, but that has always been true. Just look at those penny dreadfuls.

If you love children’s books, middle grade books, or young adult books, please comment below with your favorites and happy reading!

Selected Sources

Abadie, Elaine R., “Historical Overview of Children’s Magazines” (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 28. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/28

Bingham, Jane M, and Grayce Scholt. Fifteen Centuries of Children’s Literature. Greenwood, 19 Dec. 1980.

Carr, Felicia L. “Dime Novels for Women, 1870-1920.” The American Women’s Dime Novel Project, chnm.gmu.edu/dimenovels/index.html%3Fp=155.html. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Dixon, Diana. Children’s Periodicals. Gale: https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/intl-gps/intl-gps-essays/full-ghn-contextual-essays/ghn_essay_19ukp_part1_dixon1_website.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2023.

Hunt, Peter, and Sheila G. International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. London, Routledge, 2014.

Meigs, Cornelia. A Critical History of Children’s Literature. Macmillan Company, 1953.

Pope, Anne-Marie. “American Dime Novels 1860-1915.” The Historical Association, 6 June 2011, http://www.history.org.uk/student/resource/4512/american-dime-novels-1860-1915#:~:text=While%20it%20is%20not%20as. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Publisher’s Weekly. “New Study: 55% of YA Books Bought by Adults.” PublishersWeekly.com, 2012, http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-industry-news/article/53937-new-study-55-of-ya-books-bought-by-adults.html. Accessed 2 Nov. 2023.

Russell, Anna. “The Beguiling Legacy of “Alice in Wonderland.”” The New Yorker, 11 July 2021, http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-beguiling-legacy-of-alice-in-wonderland.

Tatar, Maria. Off with Their Heads! : Fairy Tales and the Culture of Childhood. Princeton (New Jersey), Princeton University Press, 1993.

Things I learned about from this episode: Kate Greenaway! Cool! And Hans Christian Andersen didn’t even LIKE children?! Whoa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Mary was very privileged to live in an era where it was possible, but not guaranteed, that she was taught to read and there were books, magazines, and newspapers. Whether she could access them is another question, but they existed, and for many women they were […]

LikeLike