In this series so far, we’ve had all kinds of relationships between the famous man and the woman behind him. But today’s relationship is a first because when Marion wrote her 1,400-page memoir, she barely mentions Frank Lloyd Wright’s name at all, but she still manages to let you know her opinion of him. It’s not positive, to put it mildly. Here’s the story of how she got there:

Coming of Age

Marion Mahony was born in 1871 in Chicago. Six months later the Great Chicago Fire burned down most of the city, and Marion was carried out in a clothes basket (Pregliasco, 165).

She came of age in a largely female world. Her mother was principal of a school and the breadwinner of the family. She hobnobbed with a lot of busy women nearby, who were running things like the Hull House, which provided services to immigrant women, and the Women’s Trade Union League, which lobbied for better conditions for working women. It was a progressive crowd (Van Zanten, 25).

Marion went straight from that to the very traditional patriarchal world of MIT. When she graduated with a bachelor’s in architecture, she was only the second woman ever to do so (Pregliasco, 165).

While it was unusual for a woman to get the degree, it was even more unusual for a woman to get a job afterwards. The first woman to graduate from MIT’s architecture program is case in point. She did manage to win one commission, but she got very little support either from male colleagues or even the client. She failed to complete the building and had a nervous collapse. A major publication used this as a moral example to explain why women are just physically not up to being architects (Van Zanten, 29).

Comparatively speaking, Marion was lucky. She got a job right out of school, though that was probably because her employer was her cousin. He owned the architecture practice, but as an MIT dropout, he had fewer credentials than Marion. Still, it gave her on-the-job training, and in 1898 she became the first woman to be licensed as an architect in the state of Illinois (Van Zanten, 26).

The Studio at Oak Park

By then, Marion had joined a new practice, one headed by another architect with even fewer credentials. Frank Lloyd Wright had neither an architecture degree, nor a license, but lack of any qualifications whatsoever didn’t stop him from opening an architecture practice in Chicago. He soon established a team, based in a studio attached to his home in Oak Park. The style the team promoted is called the Prairie School of architecture. It is characterized by long, horizontal lines that are supposed to integrate into the wide expanses of America’s Midwest prairies.

Marion was a wonderful addition to this new group. She designed the columns that lead to the new studio’s entrance. It’s a sculptural element, featuring an unrolled drawing of the architectural plans, with storks bracketing it on each side (Pregliasco, 166).

Marion worked for Wright (with occasional breaks) over the next fifteen years. Wright liked to hold in-house competitions for design features on his commissions, from small elements, like art-glass windows and fireplaces, right up to the big things, like actual floor plans. Marion won many of the competitions, and the winning designs were kept as reference for future projects. However, Wright did not like it when people referred to these as “Miss Mahony’s designs” (Pregliasco, 166). As the owner of the studio, he considered them his designs. In the same way that a modern employer owns the work that you create as an employee. In the same way that great artists like Michelangelo had studios of artists helping them, but the name that went on at the end was Michelangelo’s.

Wright probably thought this was completely reasonable. It is certainly what generations before him had done. Marion’s opinion at the time is a mystery. She stayed for fifteen years, so if she objected, it was still better than her other options. Which is not the same as saying she was okay with it. By the time she wrote her memoir decades later, she considered it outright theft. As I said, she barely mentions Wright by name, but he’s the only person she could possibly mean when she says things like:

“There is a certain American who, although he has artistic feeling, is really not an architect at all though he is quick on the uptake” (Griffin, 519).

Or a bit later on:

“The Chicago school died not only because of the cancer sore in it – one who originated very little but spent most of his time claiming everything and swiping everything” (Griffin, 709)

Because everything was attributed to Wright, it is frequently difficult to piece out which designs were really Marion’s.

We know she designed floor plans whose goal was to break away from a house as a rectangular box. That plan became the basis for many Wright homes. We also know that she designed at least some of the art glass windows that became a signature feature of Wright houses (Pregliasco, 167).

But Marion’s most important contribution was in presentation renderings. Technically speaking, an architect’s main job is to draw up the blueprints and architectural plans of a building. But the technical details needed on the official plan are opaque to your average, ignorant viewer, like me. What sells the client isn’t a blueprint, it’s the artistic rendering of what the building will look like when it’s done.

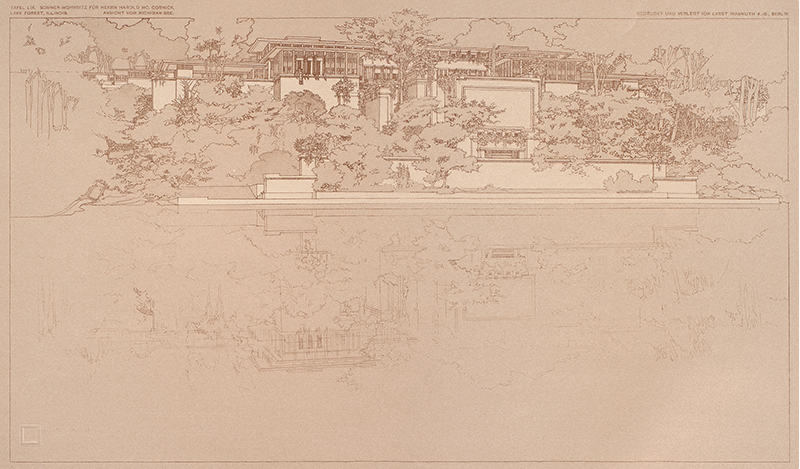

Marion excelled at these presentation renderings. Her pen-and-ink drawings are real works of art, and they were inspired by art too. Japanese prints were in vogue, and she used Japanese techniques. She kept the building itself minimalist, while adding lush foliage that dissolved the framing line. She chose dramatic viewpoints, where the building was pushed up or to the side of the paper (Pregliasco, 169). Pictures on the website.

Quite apart from impressing the customers who kept the money flowing, these drawings were also the ones that got published in journals and magazines. They were the ones that made the name of Frank Lloyd Wright famous.

This was especially true after the German company Wasmuth published a portfolio of Wrights’ work in 1910. This portfolio is considered among the top three architectural publications of the 20ᵗʰ century, and nearly half of the attributable drawings in it are copies of drawings originally done by Marion Mahony over the preceding decade (Pregliasco, 170).

She was both talented and prolific, and without her, Wright would never have achieved the reputation he eventually got.

He seems to have known that too, because in 1909, Wright went to Europe and according to Marion, he asked her to take over the Chicago office for him. Yes, of all the people he could have chosen to replace himself, he chose her.

However, she refused, and the job went to Herman von Holst, who was happy to keep Marion on, even though she said she’d only do it if she had complete control of the designing. Von Holst was happy with that, and Marion reports that she had great fun designing in this period (Pregliasco, 170; Griffin, 530).

Architecture without Frank Lloyd Wright

Nominally, this was still Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio. But that didn’t last because in Marion’s words “the absent architect didn’t bother to answer anything that was sent over to him” (Griffin, 530). Notice how she still isn’t calling him by name.

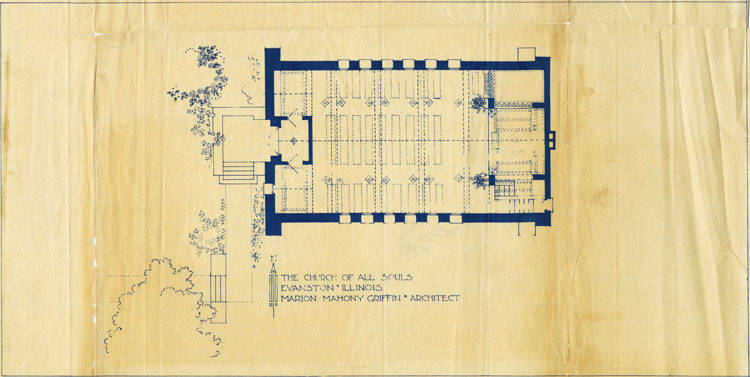

Now working for von Holst, Marion did her first solo projects, including a church in Illinois and a house for Henry Ford, of the Ford Motor Company.

Just why Marion would refuse to take over Wright’s office is something that I am not clear on. I can think of many possible reasons (some good, some bad), but one possibility is that she was disinclined to say yes to anything Wright asked because of the manner of his leaving. This wasn’t some vacation to Europe or work trip to Europe or any other very justified and legitimate reason for going. Or rather, he may have said that he was going to work and study European architecture, but the world mostly noticed that he did so in the company of a former client and neighbor named Martha (or Mamah) Borthwick Cheney. Yes, they were both married, and not to each other. Yes, they both had children they left behind.

The abandoned Kitty Wright was Marion’s friend. The studio at Oak Park where Marion worked was directly connected with the house where the Wright family lived. Marion had known Kitty for years. They both attended the same women’s study group that met to discuss education, art appreciation, and literature. Marion thought Wright’s behavior to Kitty was appalling and inexcusable (Van Zanten, 36).

Decades later in her memoir, Marion clearly still thought so because though she never references this event in particular, she’s clearly mad about much more than his tendency to accept credit for her work. She says, for example, that:

“It is a curious thing how unfruitful Wright’s work has been, apparently because of the poison of his spirit of personality and possession which kills the spiritual things” (Griffin, 791).

While the Wright family was dissolving and the Wright studio was devolving into the von Holst studio, life was changing for Marion in other ways too.

She had a brief courtship with fellow architect, Walter Burley Griffin. He had his own practice, and Marion didn’t refuse to take over management for him. She was running it even before they eloped in June 1911 (Pregliasco, 175). However, one thing had not really changed. Before, many people had mistakenly believed her work was done by Frank Lloyd Wright. Now they believed it was done by Walter Burley Griffin (Wood, 14).

A Move to Australia

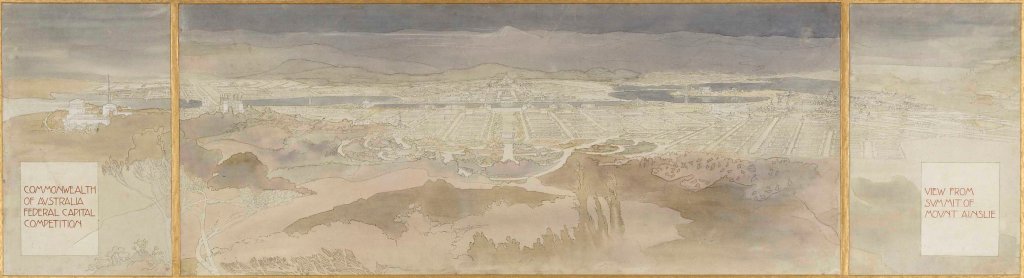

This was a partnership that would take her in entirely unexpected directions. In 1912 Walter was the winner of a competition for designing the city of Canberra, the new capital of Australia. Several contemporary accounts mention that the deciding factor in the judge’s decision was the stunningly beautiful presentation panels. They were eight feet wide, up to thirty feet long, and they folded on hinged panels like Japanese screens. They were all Marion’s work (Pregliasco, 176).

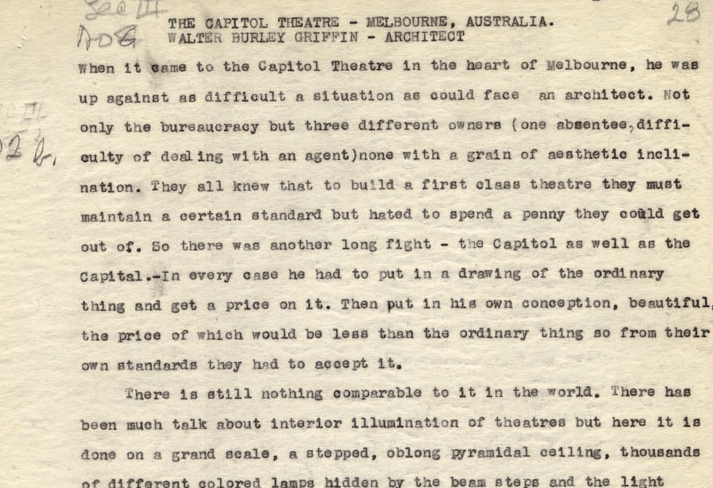

In 1914, the Griffins moved to Australia and brought Prairie School architecture to a new country with a completely different landscape. Marion managed the Sydney office; Walter managed their Melbourne office, which was 550 miles away. Together they designed hundreds of buildings, and Marion was the major designer on many of their biggest successes (Pregliasco, 177-178).

They stayed there for twenty years, and there’s plenty to tell about it, but I’m gliding over it a little because Marion had no contact at all with Frank Lloyd Wright in this period. He finished touring Europe, incorporated European ideas into his work, came home, and kept designing to high acclaim.

High acclaim from some people, anyway. Not from Marion. She describes Wright’s European additions as him staying with the same Japanese influences they had had done together “except where some European architect doing something quite different, in which case he jumped in with some such form in order to claim it as coming from himself.” But she had no good opinion of the architect Wright was copying either. His name was Le Corbusier, and she says, “such work as Le Corbusier is properly speaking not architecture at all. It is engineering, bare bones, and though it may meet the physical needs of men does not solve the spiritual problem at all. It lacks the spirit of mathematics, the spirit of music” (Griffin, 791). You may notice that Marion has a lot to say about the spirit and spiritual things in her memoir. Hold that thought. I’m getting to it.

Coming Home

Meanwhile, Marion was doing great things in Australia, and she continued doing so for 20 years. In 1935, there was another major move. Walter was invited to design Lucknow university in India, and Marion joined him. In less than a year, Marion designed over 100 buildings (Pregliasco, 179).

The India interlude was cut short by Walter’s sudden and unexpected death. Marion finished off the India projects, returned to Australia, and then returned to the United States after nearly 25 years away.

She spent her last years advocating for community planning and a better life for everyone. Sometimes this involved architecture and design, but not always. Her memoir was written partly to boost Walter’s profile in the US, but also to have her pantheistic view of the world, which welcomed many cultures and celebrated all forms of art (Van Zanten, 126, 139).

It’s not surprising that Marion thought Walter’s reputation needed a boost in the United States. By the late 1930s, Frank Lloyd Wright had built his masterpiece. It’s Falling Water, a house in Pennsylvania, and a host of other buildings from the East to the West Coast. The Griffins had spent the height of their careers on the other side of the globe, and their home country had mostly forgotten them.

What is a little surprising to me is that while working so hard to boost Walter’s public profile, Marion did comparatively little to boost her own architectural profile. The one time she was invited to address the Illinois Society of Architects, for example, she did not choose to speak about architecture (Bernstein). Her topic was anthroposophy. It’s a movement that believed in the existence on an objective spiritual realm, which was accessible to humans. The most famous proponent was Rudolf Steiner. He was a man who inspired Marion, also the abstract artist Hilma af Klint, episode 10.11.

Marion’s return to her home country was noted by the architecture community at large, but not because anyone particularly wanted her work. They wanted to talk to her about Frank Lloyd Wright, and she was a resource. She had known him in the early years.

Perhaps that was yet another grievance to add to the list. He was an international sensation, with adoring fans everywhere. Marion seems quite determined to insist that none of that was because of any actual talent.

“He was quick on the uptake, naturally artistic but never an architect, though he claimed the whole Chicago School of architects as his disciples. He spent most of his life writing articles making these claims and really was a blighting influence on the group of enthusiastic creative architects of his generation. Only a quarter of a century later has any creative architecture in the United States escaped the blight of his self-centered publicity” (Griffin, 531)

Another difference between Frank Lloyd Wright and Marion Mahony is that while he was published (many times), her memoir never did find a publisher. And to be honest, I can see why. It reads like a very rough draft, which is exactly what it is. She needed an editor. It may not have seen the light of day during her lifetime, but she eventually donated the manuscript to the Art Institute of Chicago, who still owns it, and I am happy to say, has put it online.

As far as I can tell, Marion never reestablished contact with Wright. Their friendship had irrevocably ruptured in 1910. Marion died in 1961, having long since retired from architectural work.

I am not enough judge of architecture to have any opinion on whether Wright’s work was as bad as Marion claims, or whether hers was better, as both she and some of my sources claim. I do know that he is a lot more famous than she is. At least here in the United States. That might not be true in Australia. I’m hopeful that it’s not true in Australia. If you are Australian, drop me a note to tell me if you’re familiar with Marion Mahony, or Walter Burley Griffin, for that matter.

Selected Sources

Bernstein, Fred A. “Rediscovering a Heroine of Chicago Architecture.” The New York Times, January 1, 2008, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/01/arts/design/01maho.html?pagewanted=all.

Griffin, Marion Mahony. “The Magic of America: Electronic Edition.” Art Institute of Chicago. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://archive.artic.edu/magicofamerica/supplementa/moa_text.pdf.

Pregliasco, Janice. “The Life and Work of Marion Mahony Griffin.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 21, no. 2 (1995): 165–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/4102823.

Van Zanten, David, ed. Marion Mahony Reconsidered. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2011.

Wood, Debora, ed. Marion Mahony Griffin: Drawing the Form of Nature. Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University Press, 2005.

Perhaps is am hopelessly (Boomer)old-fashioned,but I have always considered Frank Lloyd Wright’s work timeless and functional works of great physical utilile art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

spwilcen, Now you know why he was so successful, a lot of talent from other women and men in his employ.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like Frank Lloyd Wright’s work too! I was very surprised by some of Marion’s comments about him.

LikeLike